One Step At A Time

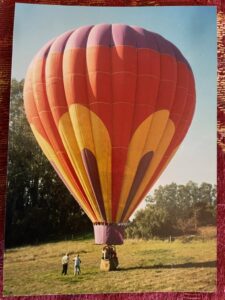

One Sunday morning, years ago- 1987, to be exact- a beautiful balloon surprised us by sweeping down from a clear, blue sky to land in the field that now hosts our lavender labyrinth.

Starr and I once got lost in a labyrinth of our own creation. I’m not speaking metaphorically; in 2019 she and I decided to plant a giant labyrinth garden in the field that lies to the south of our home. In the years to follow, we dug over a quarter of a mile of curving, raised beds and set out over 3000 lavender plants. We had a goal, but at a certain point in our construction project we got lost.

A labyrinth is different from a maze. A maze will lure you down a false path and puzzle, teach, terrorize or entertain you. A labyrinth, by contrast, offers you a single path to follow, and if you keep going, if you don’t quit, you don’t turn back, and even if you don’t cheat and “jump across the lines,” you WILL find the center. Labyrinths can be meditation tools, and they are certainly an obvious metaphor for life; sometimes the “path we’re on” in life appears to be leading us astray, even though (in hindsight) we can see we were being drawn closer to our “center” all along. Other times, our life’s goals seem to be within reach when, suddenly, our pathway veers away from our targeted destination, or even seems to cause us to reverse ourselves. When Starr and I found that we’d dug ourselves into a “dead end” in our own labyrinth we had a laugh about the irony of our predicament. Then we went back to the drawing board, back to our shovels and, after three more days of work, our “a-mazing” lavender planting had become properly labyrinthine. We are now a full five years away from having conceived of this garden, and the lavender plants are now mature and reaching their prime. We invite you to come and visit the Ladybug’s Labyrinth on Saturday, May 4th, for World Labyrinth Day.

Labyrinths have been created by many different societies and cultures around the world and some designs are thousands of years old. Starr and I modeled the labyrinth that we built on the medieval era labyrinth located within the Chartres Cathedral. But where that classic, Catholic, labyrinth is laid as a mosaic into the floor of an overarching stone building, we wanted our labyrinth to grow up out of the earth, with nothing overhead but the birds, the butterflies, and the blue vault of the heavens; an inviting garden framed by redwood trees, camelias, roses and cacti, not stone walls; we’re farmers, after all, not Popes, and the earth is our church. So, with the creation of a beautiful labyrinth as our goal, Starr and I set out, one step at a time, to create a beautiful labyrinth; here’s how we did it:

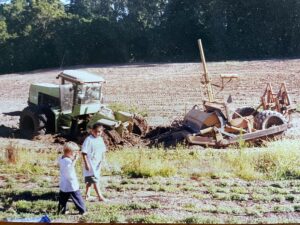

My son was 5 when we leveled the field in 2000. He and his friend, Gerardo, enjoyed the drama of seeing the big tractor get stuck in the mud.

Step One: Site Selection.

Sometimes in life we don’t get to “select.” Sometimes we have to play the cards we’re dealt. At Mariquita Farm we’re lucky enough to have several potential sites for a labyrinth so we chose the field that lies to the south of our home. The southern exposure of the site means that the field is warmer, and potentially drier than our fields to the west or to the north. Our southern field is set in a bowl with the gentle northern slope acting to shelter the site from any winds over the mountains to the north, while the southern edge of the field is screened by a riparian forest, sheltering the spot from any wind off the Pacific ocean three miles to the south. A different patch of ground, with different exposure and a different micro-climate, might have called for a different crop, but we figured that lavender might really enjoy this sunny and sheltered setting.

Lavender needs good drainage to thrive and I knew that our southern field could offer that! Life may be a spiritual journey through “a labyrinth,” but a career in farming is definitely a maze to negotiate with many false starts and dead ends. Back in the year 2000 I had this field laser leveled by my neighbor, Bobby Peixioto, who runs the Pajaro Valley Laser Leveling Company. Bobby took all the top soil off an acre of ground and piled it to one side. Then he graded the underlying clay formation until it was flat and smooth, giving the ground a slight downhill pitch to the east so that excess water would drain off. Then he spread the topsoil back evenly across the whole field. I erected an acre of metal framed hoop houses across the land with an eye to growing wintertime herbs and veggies. But a freak snowstorm came before I had a chance to plant a single crop, and it flattened my brand new greenhouses. I was crushed. I cleaned the field up of all the debris and returned the land to pasture. Until now. The soil is rich, well drained, and well rested. The field even has a pipe to it that can deliver thousands of gallons of water from my storage tanks. If commercial farming had been a costly failure on the site then maybe that was just fate telling me to take a more artistic, meditative approach to working the land in the future.

No need to panic when you’re at the top of the food chain! This kitty is the best protection from deer that a gardener can’t buy.

Step Two: Study and Research

Normally, step two would have been to build a very high deer fence around the field. But I had done that years before. Here in Corralitos, if you don’t want to build a deer fence around your land you shouldn’t even bother to farm. Lavender is not known to be attractive to deer, but that’s not all we want to grow in the labyrinth garden. Our dream for the lavender labyrinth is for it to be set in the landscape like a purple jewel, embraced by flower beds, herbs, milpas of corn, rows of roses, and by citrus orchards, and those crops definitely need protection from deer. Yes, we sometimes have mountain lions in the canyon below the labyrinth, and a healthy mountain lion will eat one deer a week, but “unfortunately” we see a lot more deer than lions looking in through the wire mesh fences. Starr and I used the time we didn’t spend building a tall deer fence to go and visit other labyrinths, learning what we could and absorbing the inspiration they offered. The Sibley Volcanic Preserve’s labyrinth in Oakland was as strange and as beautiful as it was unexpected. The Lands End labyrinth in San Francisco was majestic. The labyrinth at The University Of Saint Thomas in Houston was as calm as that city is frantic. Starr took a course from Lauren Artress of Veriditas on labyrinths. We read books, or tried. Some of the literature was too esoteric for this dirt farmer. We learned a lot.

Starr doing some “research” at San Francisco’s labyrinth.

Step Three: Field Fertility and Crop Selection:

Being left fallow as livestock pasture for nineteen years had definitely given the ground a good rest, but I wanted to get rid of turf and create a more malleable and weed-free seedbed for the lavender crop I’d be planting. Contemporaneously with prepping the outdoor ground I planted trays of lavender seed indoors of a short, purple bloomed variety of lavender called “Ellagance.” I also sourced a thousand each of seedlings of Hidcote lavender and Provence lavender. The idea was to have the shortest and earliest blooming lavenders ring the center of the labyrinth, and reserve the taller, later blooming varieties for the outer beds. I thought about what the labyrinth would look like to a Google Earth satellite passing overhead, and I imagined an open eye with a purple iris looking up at the sun.

The wild turkeys turned out to inspect the outline of the future labyrinth.

Step Four: Design Placement

Setting the labyrinth in the field was a task that called for me to march around the field with a flag on a tall stake while Starr stayed up on the hill and directed me to the left, to the right, back this way and then over there, until she found a spot that felt like the emotional center of the field. We had envisioned an eleven circuit labyrinth. We got some string, tied it to the central metal fence post and then circumscribed the outline of the outer edge of the potential labyrinth and marked it with tiny flags. It turned out to be 110 feet wide! Using the rototiller pulled behind by my little Kubota tractor I then tilled up all the ground that encircled the labyrinth site and we were left with a bright, green grassy disk of the field marking out the footprint of our future labyrinth. Starr and I looked down on the field and we were satisfied with how we had centered our garden-to-be.

The first season of digging saw us get a third of the pathways excavated.

Step Five: COVID

Step Five did not follow Step Four the way that thunder follows lightning. Life got in the way. Covid erupted. The disruption to everyday affairs that was provoked by the Covid plague would eventually “give” us the time away from our normal lives we’d need to get the labyrinth’s paths dug and planted, but the actual construction of the labyrinth was a disjointed affair that we completed over two springs, when the rain softened the soil enough to work. We measured out the width of the resting space that we wanted to have at the center of the labyrinth. We conceived of an area wide enough for a dozen people to sit comfortably and look around themselves at all the flowers and trees and birds and bees and clouds. I dug the first ring-like trench around the center and heaped up the soil to one side to form a round, raised bed about two feet wide. That first, central bed would obviously be the shortest bed of the entire labyrinth, but still my back said, “Are you kidding? An eleven circuit labyrinth? Ten rings to go?”

“One step at a time,” my meditative brain reminded my aching back. “One step at a time.”

We made the beds very high so that the lavender wouldn’t get “wet feet” in the winter. It was a lot of work, but a good move, since the first year of the crop being in the ground saw the most rain we’d seen in years. In this photo one of our cats is inspecting the work.

Step Six: Getting Some Help

We were still farming in the greenhouses near my home as the impact of the Covid restrictions hit. My employees there needed as much work as they could get, but the farm’s winter sales were uneven. When the harvests were light the guys would come over and help me dig the labyrinth so that they could get enough hours. When we were busy on the farm the gestating labyrinth would quietly wait in its field for us to return. Meanwhile, back in the greenhouse, the tiny lavender plants were growing. We up-potted the seedlings from 250 cell trays to trays with bigger one square inch cells, and finally up to 4 square inch pots.

Starr dug little pockets in the planting beds and filled them with water before she transplanted the tiny lavenders. That’s about all the water (besides rain) that most of the plants have ever received.

Step Seven: Irrigation

When the eleven concentric paths had been dug out and the planting beds raised and smoothed off it must have looked from above as though the field had a target carved into it. At that point I dug a ditch from the edge of the field that cut across the beds through the center of the labyrinth and I laid out a pipeline with half a dozen risers coming off of it so that I could connect up hoses for hand watering or install a drip irrigation system. Given that below the topsoil layer there’s a deep bed of water-retaining clay soil I was hoping that after an initial “watering in” the young lavender plants would be able to tap into that subsoil moisture. Then too, there’s subsoil moisture seeping down from the higher ground as the irrigation I provide for the citrus grove soaks into the soil. I’m hoping I won’t have to irrigate the labyrinth, but you never know, and the time to install irrigation is BEFORE the crop is planted, not as an afterthought.

Step Eight: Design

An outline of the Chartres Cathedral labyrinth gave us the blueprint for the map of our labyrinth. Starr made copies on sheets of paper that we could clutch at as we marked out all the spots amid the concentric garden beds that we’d have to cut or fill to create the sinuous pathway that guides a seeker to the center. Starting from the outside Starr and I began digging openings between the beds to create a path to the center and plugging up some of the trenchlike pathways to create the looping, labyrinthine path. We had the Chartres Cathedral’s maps in our hands to follow. How hard could it be?

Well, it wasn’t as easy as it seems like it ought to be and as we tried to dig our way to the center we kept bumping into dead ends or looping back on ourselves. We had created a maze! We had a laugh about our situation, took a rest, and returned the next day. And the next. On our third day we made our way to the center of the labyrinth without cheating and hopping over the beds. Success! We sat down in the calm center, looked back up the hill across the lemon orchard and took a deep breath. All that remained to do was …..,.,

Starr and her son, Malakai, planting the thousands of lavender seedlings.

Step Nine: Planting

I brought the 3000 little lavender plants over from the greenhouses, one variety at a time. There was still a lot of moisture locked up in the raised, earthen beds so all we did was to mark out location for each plant by removing a measured shovelful of soil and then Starr filled each hole with of water. One by one she planted the little lavenders and smoothed the soil out around them. Our three cats came down the hill and watched her work with great interest. Wild turkeys and Valley Quail came in the evening to walk the labyrinth, peck at ants and seeds and sprouts and meditate on the changes to their field. The deer and the mountain lions looked through the wire mesh fence and wondered what fresh craziness we were up to.

Starr’s granddaughter has helped with weeding the labyrinth. She’s 8. Here she is with a bucket of bindweed.

Step Ten. Weeding and watering.

Watering didn’t turn out to be much of a problem. As it stands, after two years Starr has only ever watered a few struggling plants with a splash or two of water, and last year we didn’t water anything even once! The lavender plants did reach down into the subsoil and find the moisture they needed. The beds are raised very high and the trench-like pathways are dug deep, so despite having two very wet winters in a row the lavender never flooded or died because of poor drainage. Naturally, the weeds also thrived-especially the bindweed. We have spent plenty of time weeding the labyrinth but as the lavender plants grow the task gets easier. We’ve had some amazing volunteers come and help from time to time. Weeding the labyrinth is a frequent “meditation” for Starr and I too. We poke along the beds looking for weeds and we enjoy the “om” buzz of the honey bees as they work the flowers for nectar. We also see lots of Bumble Bees and butterflies in the warm months when the crop is in flower.

These friends chose to come to our lavender U-Pick and fill their cars up with fragrant bunches of flowers.

Step Eleven: Sharing

Our labyrinth is a garden that we harvest lavender flowers from but it’s also a work of art and we created it to share with you. Our first event of the year will be our celebration of the 16th Annual World Labyrinth Day on Saturday, May 4th. The roses should be looking good then too.

Later in the season when the lavender patch is in full bloom we will host some U-Pick events in the labyrinth as well. Keep an eye on the website and on the newsletters as we will be posting details and updates about registration .

|

There was enough subsoil moisture present in the labyrinth’s deep beds so that we only needed to spot water a few struggling seedlings the first year the garden was planted. Here you can see the whole labyrinth but the lavender plants are still too small to notice.

Last summer the plants really began to shape up. Here I am walking the perimeter.

-

Andy with an armload of lavender.

The Google Earth satellite caught an image of the labyrinth last year in mid spring. I can see the young corn plants below the labyrinth paths but I hadn’t yet planted the marigold crop on the other side. The lavender plants were still small in this picture- they’ve grown A LOT!