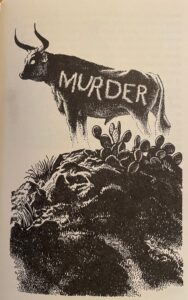

Never Turn Your Back On A Bull

Soda Lake, in the Carrizo Plain National Monument, is often dry for for long periods of time.

A recent visit to the Carrizo Plain National Monument got me thinking about sex, violence, and botany. If you’re still unfamiliar with the Carrizo Plain, know that it sits astride the San Andreas Fault, tucked in between the Temblor Range to its east and the Caliente Range on its west. “Temblor” means “earthquake” in Spanish and “Caliente” means “hot,” so you can make a pretty good guess as to what usually goes on out there. Maybe you’ve traveled down I-5 to LA from the Bay Area along the westside of the San Joaquin and looked out the window at the empty, bald, hills off in the distance. That landscape is usually a baked, drab, dun color, but for a few weeks each year- if the land has been blessed with any rain- the hills and plains can be a bright, grassy, green splashed with a psychedelic array of brilliant yellows, oranges, purples and blues as wild flowers explode in glory. I’ve been going out to the Carrizo off and on since I was a child because my father was a native plant botanist, and it was he who first told me, “Never turn your back on a bull.”

In the aftermath of a 2017 LA Times story on a Carrizo “super bloom,” it seems as though half the world has found out about this relatively recent addition to our National Park System and, when the wild flowers do happen, a visitor may even experience an incongruous LA style traffic jam on the typically lonely Soda Lake Road, a good twenty miles of which is still just a dirt track across an empty land. My father didn’t need a colorful wildflower display to attract his attention. The Carrizo Plain is almost a desert, and it is an “endorheic basin,” which means it is a sink with no drainage. What water that does fall onto or flow into the Carrizo Plain puddles up in Soda Lake. But the water soon evaporates and Soda Lake is usually no more than a baked, dry, salt playa. The Carrizo Plain is too droughty and remote to be of much use agriculturally, in stark contrast to the neighboring San Joaquin Valley, which is one of the most intensely managed agricultural valleys in the world. For California native plant botanists, like my father, the Carrizo Plain represents one of the last opportunities to study an environment that approximates the now extinct native ecosystems of California’s Central Valley. Dad began going to the Carrizo when he was a grad student at UC Berkeley beck in the mid-1950s, long before the land was framed as a national monument, and when the idea of a traffic jam on Soda Lake Road would have been insane.

Cattle still range across sections of the Carrizo Plain.

Today, as you enter the monument on Soda Lake Road from the north, you cross a cattle guard and there is a yellow road sign with an iconic image of a cow, intended to alert the driver that there may be range cattle crossing the road ahead. I’m sure that sign didn’t exist back in the fifties, but if dad had seen it he would have smiled. My father grew up on dairy ranches up and down the Salinas Valley and he knew as much about cows as he wanted to. Anyway, the prominent outline of a huge, swollen udder identifies the creature on the sign as a milk cow, which is funny because milk cows are just about the last creatures you’d be likely to see on a seared and scant range like the Carrizo Plain. The rough and rowdy breeds of beef cattle that can sniff out distant waterholes and lick up enough dry grass to survive on an open range are quite different animals in physique and behavior than their placid dairy cow cousins. Dairy cows are like sports cars that must be given the best fuels to perform; they beg to be fed with leafy bales of alfalfa, and they must have LOTS of water available if they are to make all that milk. Dairy cows are generally docile by mature. It is interesting, though, that dairy bulls have a reputation for being quick to anger and prone to violence.

Dad did have a story about a kid he knew on one of the ranches he grew up on who dreamed of escaping the smelly routine of life on a dairy for the excitement and glory of the rodeo arena. The unfortunate boy thought that he’d practice for the big time by riding a Holstein bull in the dairy pen. The kid perched himself on the roof of a shade shed until he had a chance to drop himself onto the back of a passing bull as it headed out into the sun to eat, whereupon he was promptly thrown to the ground and gut stomped to death. Never turn your back on a bull, and definitely DON’T get on a bull’s back! Bull riders at the rodeo may be incredible athletes, but they are crazy to the bone.

A lovely stand of Phacelia rimed with frost, photographed just after dawn at the south end of Soda Lake.

Many consumers think that if a bovine critter has horns then it’s a bull. Not so! Female cattle usually have horns too, if they haven’t been cut off or burned out of their infant skulls in the bud. Male deer, or bucks, have antlers and female deer, or does, don’t. An antler is different from a horn. A buck will shed its antlers at the end of the rutting season. True horns are bony structures that are part of the skull. A cow can come into heat at any time of the year and a horny bull will always be ready to breed her. It’s not for nothing that a crude and popular term for the condition of being sexually excited is to be “horny.” A healthy bull is always ready to mount a cow or a…..When I was a teenager working on the Bell Ranch in upper Carmel Valley, two new, purebred, Angus bulls were delivered. The young bulls would be quarantined for a couple of weeks before being introduced to the herd so that we could be sure they didn’t harbor any communicable diseases. The bulls were excited after their bumpy trip in the livestock trailer and one bull mounted the other. “Will he be interested in cows?” I asked. The cowboy who had just unloaded the pair laughed. “Look, kid, ” he said. “That bull is so horny he’d screw a knot hole.” An indelicate observation, perhaps, but not inaccurate.

This young bull of mine was tame, as bulls go, but you should never turn your back on a bull. They aren’t dumb, but they can easily forget that they have been “domesticated.”

Cattle are ruminants. That is, they have four stomachs and, after walking about the landscape and grazing, they will cough up the grass they’ve just consumed from their first stomach, the rumen, and settle down to “chew their cud.” As they chew away and “ruminate” cattle look introspective and peaceful, which has led some writers to use the verb “ruminate” to mean “to think deeply.” I’m not saying that bulls are not capable of having deep and philosophical thoughts, but even a ruminating bull can be moved to a display of fierce, primal violence in a heartbeat if provoked. A bull’s skull is so very thick and their gaze can be so inscrutable that we can’t ever know what exactly is going on mentally between their horns. It’s a good practice to keep oneself a respectful distance even from a ruminating bull and “let the mystery be.” Dad knew all this when he turned his blue Ford sedan down lonely Soda Lake Road back in the mid fifties, his new wife riding shotgun, and headed out into the boonies to look for rare, endemic milkweeds.

My father as a young man in the Salinas Valley. There’s an irony at play in this photo. Maybe the tractor was stuck in the mud, but he wasn’t, and he’d soon flee ranch life for a career in academia. I, by contrast, have a genius for atavism, and I would flee a life on a scientific field station for a career of getting stuck in the mud on a series of farms. Go figure….

Soda Lake may usually be dry, but every once in a while it has standing water in it. Last week, when we visited, we saw a real lake with water and ducks. More often, Soda Lake boasts a crust of white salt on top of a slurry of sticky mud. Even when the lake bed is dry from its sun baked surface all the way down to hell it’s still not a good idea to drive off the road. It is easy, even for a four wheel drive vehicle, to get stuck in Soda Lake’s crunchy, slimy salt. It’s a long road. And narrow. When you are driving it you can really get a feel for the wide open spaces of the Old West, and you feel glad you’re not walking. The middle of Soda Lake would be a terrible place to get stuck or break down. The nearest tow truck, even today, would be hours away and back then, of course, there were no cell phones. The sedan kicked up a little cloud of salt dust as it rolled down the narrow road and the odometer scrolled the miles away.

My mother as a young woman, clowning with a cigar in a bathroom at UC Berkeley. Dig the Saddle Oxfords! So chic!

Yes, it may have been a long trip, and the morning might have been heating up past the comfort zone as the sun rose higher in the sky, but dust, a sore butt, and annoying heat are just some of the personal sacrifices that botanists (and their partners) must expect when they set out on a quest to find rare, endemic milkweeds. And milkweeds really are worthy of attention, even if they are not flashy like orchids or scented like roses. Milkweeds host Monarch butterflies, and without them the Monarchs cannot survive.

My father was in that generation of plant ecologists who were moving past the era when doing botany meant going into a “dark continent,” “discovering” a plant that the “natives” had known about since God, and then naming it after themselves. Academic colonialism was giving way to a new, more holistic, interdiciplinary approach to scientific inquiry which sought to explore the web of life and the interconnectivity of all living organisms. “Woke” botany? The Carrizo Plain may not have a flashy waterfall like Yosemite, or a spurting geyser like Yellowstone, but the dry hills and the dusty flatland have secrets to reveal.

Mom and dad were most of the way across the lakebed and nearing the grasslands when they saw a large, dark object in the road ahead. As they draw close they observed that their path was blocked by a big, black Angus bull, apparently asleep. Dad approached but stopped the car at some distance, expecting the bull to wake up and move out of the way. But the bull was content to snooze in the warm sun. He had all the time in the world to ruminate on deep thoughts.

Dad honked his horn.

The bull opened one eye, but he didn’t move. What does scientific inquiry into the interconnectedness of all living beings matter to a 1800 lb, drowsy, black bull on a vast salt flat? Maybe later he would walk to to the hills, eat some grass and check in on his harem of cows. But for now…..snore….

Dad honked again.How annoying! The bull opened one eye and observed a humble, blue, Ford sedan. He swished his tail. The morning had been more pleasant when it was just him and his halo of flies, thinking his deep thoughts and chewing his cud.

Dad didn’t have all day to wait. Mom was hot and tired. They didn’t dare drive around the bull for fear of getting stuck in the loose, slimy salt. Dad edged the car forward and honked again. This was too much for Mr. Bull. He was the black Lord of the Plains. He ceded his path to nobody, man or beast. He’d been peacefully enjoying his “alone time” but now that the tranquility had been disturbed by this meddlesome couple and their absurd car he’d show them who was boss. The bull lumbered to his feet in rage to face his new enemy. The world would soon see who turned tail and ran.

The bull lowered his head. Dad put the car in reverse; he couldn’t turn his back on the bull because if he tried to turn on the narrow dirt track he’d likely get stuck in the salt and be stranded miles from anywhere with a new wife while a mad bull pummeled and gored his sedan.

The bull lowered his head. Dad put the car in reverse; he couldn’t turn his back on the bull because if he tried to turn on the narrow dirt track he’d likely get stuck in the salt and be stranded miles from anywhere with a new wife while a mad bull pummeled and gored his sedan.

The bull charged. Dad hit the gas. Bulls move fast. Of course, a Ford can go faster than a bull under laboratory conditions, but backing up at high speed on a narrow, dirt road is a nerve racking proposition. I’m here to tell this story, so obviously my parents escaped the wrath of the Lord Of The Plain to tell me the tale, but I smile when I see the yellow diamond shaped sign with the placid dairy cow and the words, “Impassable during wet weather.” It is rarely wet on Carrizo Plain, but that doesn’t necessarily mean that the road is passable on a hot, dry, summer day.

There will be no bulls attending our Saturday, May 4th, celebration of World Labyrinth Day. Yes, I know that the original Labyrinth was created by Daedalus and Icarus for King Minos of Crete to constrain his bull headed monster, the “Minotaur.” The story of the Labyrinth is another of those foundational, mythic tales of the Western tradition that the moralistic book-burners among us would ban if they ever chose to read Classic Western Literature. It’s said that Pasifae, the daughter of the sun, brave Helios, out of an ocean nymph named Perse, grew up to be the Queen of Crete, and by some accounts she was also a powerful sorceress. But Pasifae, herself, was put under a cruel love spell by Aphrodite, which provoked in her heart a powerful sexual lust for that perfect, white Creten bull that her husband, King Minos, kept in his royal herd. To realize her amorous intentions, Pasifae contracted with Daedalus to build her a wooden, cow-shaped crate with a glory hole at one end. You’ve heard of the “Trojan Horse?” Well, this was the “Cretan Cow.” Daedalus draped his construction with a cow hide to approximate the scent of a bovine in estrus and Pasifae backed into her love shack. The Royal corral gate was opened, the perfect white bull entered the pen, and one thing led to another. In due course, Pasifae gave birth to a bull-headed male child, named Minotaur. “(Mino” for Minos, the cuckold king, and “taur” for Taurus, which means “bull,” as in the constellation, Taurus.) King Minos was NOT happy and he incarcerated the half bovine bastard in the Labyrinth. But our labyrinth is peaceful and inviting. We followed the outline of the labyrinth that was constructed in the Middle Ages at Chartres Cathedral when we created ours. World Labyrinth Day is a moment that people observe all around the world by a silent, meditative walk in a labyrinth as an expression of hope for peace.

If you can’t make it to the farm for World Labyrinth Day consider coming down for one of our seasonal workshops, like our Create A Garden Stepping Stone event on Saturday, June 8th which includes a labyrinth walk.

The Carrizo Plain in 2023 with more flowers but no water in the lake.

Range Cattle in the Temblor Range. The Carrizo Plain National Monument uses range cattle as a tool to remove annual Mediterranean grasses which are “weeds” in the context of preserving native California plant species.

Hi: I’m a cow, not a bull, and I have horns.

.

|