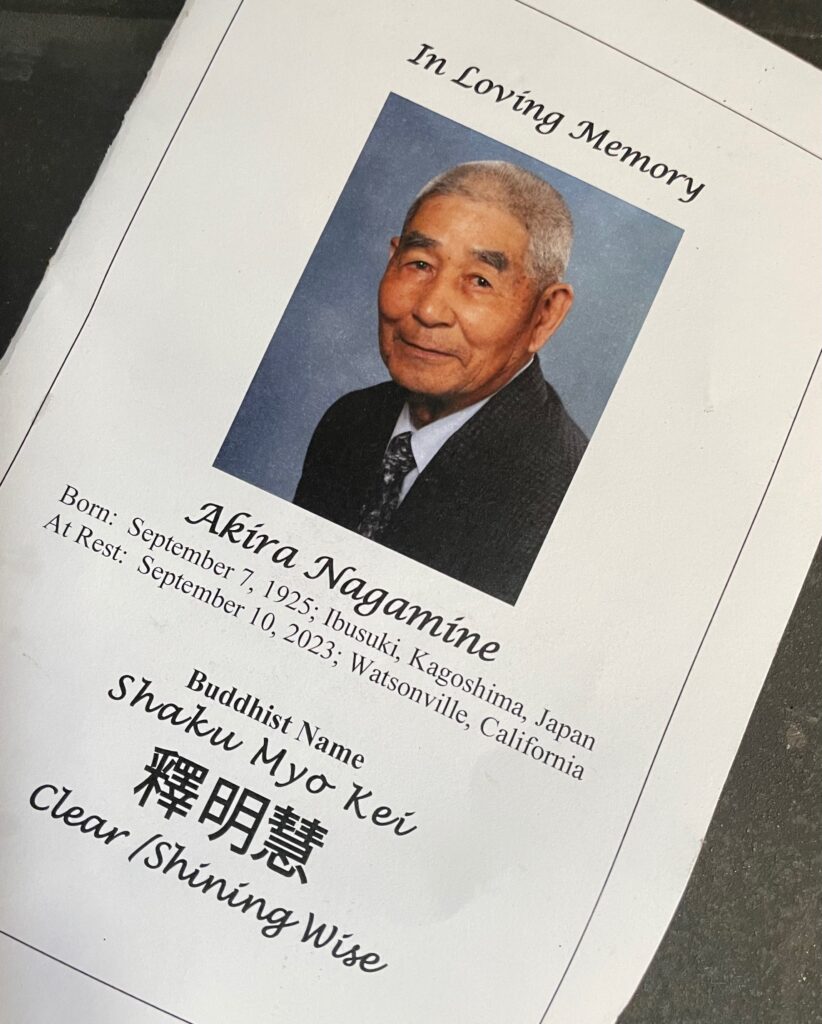

In Loving Memory

The sanctuary of the Watsonville Buddhist Temple was lined with huge displays of colorful flowers. People dressed in black filed in until the room was full. It was quiet. There was incense. There would be a chanting of sutras and the Dharma message would certainly be about the impermanence of all created things and the inevitability of suffering and loss. We were gathering together to honor a prominent local farmer, Mr. Akira Nagamine, who had just passed away at ninety eight years of age. While it can’t be a surprise when a very elderly person dies, there was still a sense of shock in the room. Mr. Nagamine had seen so much life, and was so relentlessly determined and energetic, that he seemed as much a force of nature as one of its creatures.

The sanctuary of the Watsonville Buddhist Temple was lined with huge displays of colorful flowers. People dressed in black filed in until the room was full. It was quiet. There was incense. There would be a chanting of sutras and the Dharma message would certainly be about the impermanence of all created things and the inevitability of suffering and loss. We were gathering together to honor a prominent local farmer, Mr. Akira Nagamine, who had just passed away at ninety eight years of age. While it can’t be a surprise when a very elderly person dies, there was still a sense of shock in the room. Mr. Nagamine had seen so much life, and was so relentlessly determined and energetic, that he seemed as much a force of nature as one of its creatures.

Here at Mariquita Farm we knew Mr. Nagamine as “Senior,” or “El Senor.” Over the past eight years I’d had the opportunity to lease several of his greenhouses on Hikari Farm for my own production, so we worked right alongside Senior and his crew. We even grew some of the same crops as Senior, like mizuna, shungiku, shiso, and Akahana mame. I’d keep an eye on everything Mr. Nagamine did, hoping to learn by example. I know he observed my practices and he’d be especially curious when he’d see me grow a crop he was familiar with but which I’d harvest or present it in an unexpected, or non-traditional manner, like harvesting tiny mizuna plants for green salads rather than waiting until the crop was large and robust and then bunching it. Senior was a traditional Japanese farmer- truly “Old School”- but his curiosity and interest in the world made him seem far younger than his years.

I’ll always remember Senior seated at his workbench in the packing shed, carefully sorting and bunching the “negi,” or Japanese scallions, that were one of his specialties. Most commercial farms have their workers wad green onions into bunches as fast as their hands can snap the rubber bands, but that was not Senior’s style, not “Old School.” Senior had a reverence for negi that were properly grown, harvested, and packaged. Negi are not “just green onions.” A properly grown spear of negi can take almost a year to produce and it might have a foot of pure, white, tender stalk under its display of deep, green leaves. And a proper cook knows how to utilize and appreciate every centimeter of the negi onion, from its roots to tips of the pointed, tubular leaves. I don’t want to put words into his mouth, but it’s possible Senior didn’t believe anyone under 60 even had the skills, appreciation, or wisdom to bunch negi correctly. At any rate, Senior bunched most of his crop himself, and I’m sure that it was as much a working meditation for him as it was a chore or responsibility.

One morning my once-upon-a-time employer, later business partner, and always friend, Toku Kawaii, called me up. She had a childhood friend visiting from Tokyo who would like to see a bit of the “real” California that lies beyond the freeways, malls, and convenience stores; could the two of them visit the farm?

“Of course!”

Toku and her guest arrived at the farm gate and I went to greet them. They stepped from their car, chatting in Japanese. Senior may have been 92 but he could hear plenty well when he wanted to. And he heard two women outside speaking Japanese, so he abruptly set his negi aside and popped out to see who had arrived. I introduced Senior to Toku and her friend and he was beaming. He welcomed them to Hikari Farm and asked them if they wanted tea and a visit to the greenhouse.

“But, of course!”

So, in due time, we entered the first greenhouse, a huge, glass enclosed space that Senior had planted out in orderly successions of his principle crops- Napa, mizuna, shiso, kabu, daikon and, of course, negi. The women admired the tidy crops in their neat rows and they enjoyed Senior’s animated answers to all of their questions. I can’t say I learned much from their conversation, because I can’t speak Japanese, but listening to the three of them speaking did remind me of Senior’s dexterity with language.

Mr. Nagamine was born into a farming family in rural Kagoshima, Japan, in the first part of the 20th Century, so Japanese was his birthright. But he could speak Mandarin too. In 1944, as a 19 year old Akira Nagamine was drafted in the Imperial Japanese Army and shipped off to the war in Manchuria. The war soon ended, but in the chaos of “peace” the Japanese soldiers in Northern China were abandoned to their fates as the Chinese Communists fought the Kuomintang. It would be eight years before he could be repatriated to Japan. During that time Mr. Nagamine lived by his wits, by his positive energy, and by his will. Senior Nagamine’s negi were tender to the core….but Senior was a very tough man. When Senior and his brother immigrated from Japan to America they found work first in the strawberries, so Senior learned to speak Spanish. They saved enough money up to buy their own farm and he learned English too,

When Toku, her friend, and I reached the beds of radishes, Senior asked his new friends a rhetorical question; “Do you enjoy daikon?”

“Of course!”

So Senior set to picking each of his guests a daikon root to take home. The first root he pulled was giant, but it had some unfortunate scarring from Cabbage root maggot, so he set it aside and searched for another. The second daikon that Senior pulled was 24 inches long, two inches wide, and pretty clean, but still, if you looked, you could see discoloration at the tip from root maggot damage. And the third root too displayed a bite mark or two, if you really looked. Senior reached for another daikon.

Toku could see where this was going and she made it clear to Senior that these roots that he’d already picked were spectacular and more than enough. Senior grudgingly acknowledged her concerns and stopped pulling roots, but it didn’t come easy. Before his later-in-life career as an organic grower of traditional Japanese vegetables, Senior had been a successful cut flower grower and shipper. Flowers can hardly help but be “pretty” but Senior always aimed at “flawless.” for his blooms, and he carried that baseline expectation of perfection into his life as a vegetable farmer. I’m not sure he knew the word “mediocre” in any language. In his own eyes he might have fallen short by gifting Toku-san a merely spectacular daikon, but the women had a grand time. Mr. Nagamine had a great time too, and I’m left with a treasured memory of a very pleasant morning with friends.

I’m glad I got a chance to get to know Mr. Nagamine. Sometimes I’d come into the farm in the morning and I’d be crabby because the wholesale prices were so crappy, or the weather wasn’t cooperating with my designs, or a pile of paperwork at home that I absa-f-inlutely didn’t want to deal with was waiting for me back at home, or my back hurt, or my tires were low,. And then I’d see Senior methodically checking his side of the greenhouse, frowning at the weeds until they wilted and coaxing his negi to grow straight and tall. “Holy cow,” I’d think. “I’m 63 and Senior has thirty five years on me and he’s not complaining; his stuff looks great, his customers appreciate his efforts and he has a good attitude. So shut up, Andy, and buck up. We live in a paradise so enjoy it while it lasts.” Serious respect!

So there was a Dharma message from the Reverend about the impermanence of all created things. “Every introduction will inevitably lead to a parting, to a “goodbye” if we’re lucky, to an unresolved sense of loss if we never get to say our goodbyes to our loved ones or make our peace with those with whom we had misunderstandings. Death and sadness are inevitable and every religion, every culture, has figured out ways to help people confront this reality.

I’m not a Buddhist so attending Mr. Nagamine’s memorial service was a learning experience for me. If anything, I’m a lapsed Lutheran. I can remember the Lutheran pastor talking once about religion and about how some people just want to treat the array of religious expression we see in a diverse place like California as though Ultimate Truth is a “smorgasbord” of sorts where we just pick and choose different practices to follow or beliefs to endorse as though they were so many “hot dishes” we could serve ourselves with.

“Yeah, that’s me,” I thought. I’m as Californian as the day is long and I’ve caught myself looking over the various religious convictions I’ve been exposed to and thinking, “nah- that looks like jello salad with mayonnaise,” or “yeah; I can swallow that.” What can I say? I’ve been exposed to diverse traditions and I was schooled in scepticism when I got a degree in Western Philosophy at UC Davis, so being a true believer comes hard. But that doesn’t mean I think that all spiritual expression is “jello salad.” No. Grief and loss are real and while we can’t ever change that we find ways to make beauty out of pain and we keep on plugging away. Day of The Dead celebrations are one way that some cultures have chosen to find beauty amidst grief. Following in the Mexican tradition you can see what we’re doing for the Day of The Dead, or Dia de los Muertos, by looking at our events page..

![]()

This year Starr and I have again created an extensive planting of marigolds as an exercise in farming, gardening, art, and meditation. Marigolds are appreciated in a number of religious traditions because of their rich color and pungent scent. With over 3000 tall marigolds planted around a huge lavender labyrinth the whole field is practically a shrine crafted from plants, but we’re putting together a small altar to honor the loved ones we’ve lost. This year we’re opening the farm up for a Day of the Dead, “Dia de Muertos” celebration in association with the “little bears” from Osito restaurant in San Francisco. You’re invited to come share a traditional celebration meal that Chef Seth Stowaway and the crew from Osito will put together on Saturday, October 28th. Come and walk the labyrinth, take in the amazingly bright and beautiful marigold planting, hear stories, and join in several traditional Mexican Day of the Dead activities like face painting, the gifting of sugar skulls, and the sharing of the Pan de Muertos. Maybe you’ve got a photo or memento that you’d like to contribute to the community ofrenda. Or pick some marigolds and take them home to fashion your own personal bright and aromatic altar. The farm is beautiful right now. Don’t miss out on your ticket to this fall event at Mariquita.com

See you soon!

Starr and Andy

Mariquita Farm

The work never stops here, and we welcome volunteers. We can especially use help weeding the labyrinth since we use no herbicides. During the rose season it’s great to have some help “Dead-heading” the roses. Right now it’s bean season so we’re threshing, winnowing, and sorting beans. Here’s the link to our volunteer signup. https://www.mariquita.com/friends-of-ladybugs-labyrinth/

As always, keep an eye on our website or subscribe to our newsletter for info on upcoming pop up tomatopallozas and events. https://www.mariquita.com/events-and-workshops/

Thanks, and we hope to see you soon.

© 2023 Essay by Andy Griffin

© 2023 Essay by Andy Griffin