Letters From Andy

Ladybug Postcard

Three Weeds’ Tales

Wild arugula growing in a lemon balm patch

Here’s an irony: My father was a California Native plant ecologist who dedicated his life to the study and preservation of native species, and yet I grew up to be at least partly responsible for introducing at least three weeds into the California ecosystem. If a weed is a “plant out of place,” then every weed must have an appropriate place that it naturally comes from and also a story of how it immigrated to its new environment. Here are the stories of three different weeds that I can tell from first hand experience.

My father, Dr. James Griffin, would have been 90 last week, and he’s been on my mind a lot. He didn’t do marine botany, but it was hard to find a dirt road or trail in this state that he hadn’t made his way down at least once to inventory the vascular plants. He’d be the first one to tell you that a vast amount of the plants that blanket California’s wild lands are invasive species. The grasses that cover the fields with green in the spring and gold in the summer are Mediterranean annual species that came into California as burrs and stickers in the tails of the long horned cattle that the Spaniards brought with them from Europe through Mexico.

Arugula is such a popular salad green on the West Coast that right wing pundits have chosen it as the appropriate fodder for bicoastal elitist libs, but arugula started out as a little weed in the barley fields of ancient Egypt. Arugula is in the mustard family and has always been a popular salad herb. The Egyptian farmers that cultivated some of history’s first fields of grain would have plucked the broad, tender leaves of young arugula from between the slender young, emerging blades of barley so that the grain crop wouldn’t be choked out. The arugula “weeds” were eaten too, but they needed to be controlled lest they damage the cash crop. As the culture of grain spread north out of the fertile crescent, arugula followed along. Soon Greek peasants were sowing grain and weeding – and eating the arugula. Then came Italy, then France. But if arugula traveled to France as a weed it flew into California on a magical white tablecloth.

Nowadays, with the oceans of pre-washed salad greens available in every supermarket, it can be hard to remember when salad greens like arugula were hard to find in California. My first job on a vegetable farm was working on a little Biodynamic, French intensive garden on Garden Highway, just north of Sacramento. The farm’s owner worked at Chez Panisse in Berkeley and they bought all the produce. They wanted tender young greens like arugula for their mesclun salads. Because the arugula seed was next to impossible to source, the restaurant brought us back packets of seed from France. When I went to work on Star Route Farm in Bolinas we ended up working with them too and we made endless plantings of arugula. Inevitably, some of that arugula went to seed along the edges of the field, where a stray plant here or there conspired to escape the disc harrow when the fields were turned under.

Twenty years after I left Star Route Farm, I was there on a visit, and I took a walk up Pine Gulch Creek, which borders one of the fields. I was surprised and amused to see a number of arugula plants growing wild in the weeds beyond the edge of the tilled beds. And I found a number of wild mustards that appeared to have leaves that had many characteristics of arugula, as though the two cousins had crossed. I wouldn’t worry about spoiling the gene pool for the wild mustards, though, since the wild mustards were also invasive species from the Mediterranean that have made California their home.

—

Tomatillo weeds in front of our beehive

The second weed that I’m at least partially complicit in introducing is the Tomatillo de Milpa. Everybody is familiar with the tomato-like and tomato sized Tomatillo that is so common in Mexican cuisine. But the large, green, commercial tomatillo has an unruly, weedy cousin, the Tomatillo de Milpa, which sets a generous crop of tiny, somewhat dry and acidic fruits that range in color from green to straw to purple.

The plant has its fans. Zuni Cafe, for example, has often requested the “Milperos” in lieu of the plumper, more commercial cultivar. I hadn’t heard of the crop before I moved to Watsonville. I shared my home here with the Campos Family for a couple of years, and they were from a ranch outside of La Barca, Jalisco. “Country living is great,” Ramiro Campos told me one day. “It’s so nice to have lots of space and keep donkeys and chickens and have a big garden.” So I invited Ramiro to make a garden here, and he went after the task with gusto. He showed me a handful of tomatillos de milpa that he’d brought with him from his home ranch to plant because, as he said, “no garden should be without a tomatillo de milpa.” And we’ve had tomatillos de milpa ever since. These humble plants express a vitality and fertility that rivals any other weed I’ve ever met. But at least I can make a really nice green salsa without leaving the property almost any day in the summer or fall.

—

My last weed is another refugee from Southern Europe. Nepitella is a mint family member that prefers a very well drained soil and can tolerate drought. It seems as though every region has a native mint, which is appreciated for its unique culinary properties. Nepitella is also known as “Roman mint,” and it is a popular herbal accent to many a Roman and Tuscan dish. When I was regularly selling in the Ferry Plaza Farmers’ Market in San Francisco, a frequent market shopper brought a nepitella plant to my stall from his family’s garden in Rome. “I’ll give you the plant if you’ll grow it and bring it to market so that I can have a bunch of it now and then.” I’d had customers, like Delfina in the Mission or Scoma’s in the Marina, asking after nepitella, so I went after the task with gusto.

Nepitella, aka Roman mint, growing wild in our canyon

Ever since then, this perennial herb has been a steady, if slow, seller. At one point, years ago, I planted it at the edge of my home field so that I could keep enough going to satisfy my customers without getting in the way of regular use of the field. When the sales picked up I moved my planting to the greenhouse where I could be more assured of steady winter production. This spring I was walking my fence lines at home, looking for a hole where a marauding tribe of deer might have broken through into my farmed ground. I didn’t find any holes in the fence, but I did find a vibrant population of hardy nepitella plants beyond the fence and spreading down into the Pinto Creek gulch. The Romans may like nepitella, but the deer sure don’t; the plants were fluffy, aromatic, and happy. What would my father think? I’d have to make him a pasta dish and season the sauce with some fresh nepitella to justify myself.

© 2022 Essay by Andy Griffin

Photos by Andy Griffin

I Beg Your Pardon

Purslane, cultivated as a crop

“April showers bring May flowers,” goes the old saying. If they were being accurate, the cliche makers of olde could have added: ”…and weeds too.” After a punishing period of drought we’ve finally had a few April showers, so we can expect plenty of weeds in May. I’ll be crabby about all the weeding we have to do this spring, but today, instead of complaining about the added labor costs, I’d like to change up the narrative and talk a bit about the positive role weeds can play in agriculture if we let them. But first, what is a weed?

Weeds are perhaps most charitably defined as “plants out of place.” This formula sounds good as a start but this clever quip reveals more about the person speaking than it does the plant in question. An objective observer has to ask, “‘Out of place’ according to WHO?” Take the archetypal “weed,” Cannabis sativa, for example. Talk about a “plant out place;” weed is a plant SO “out of place” that its very existence has been outlawed by the US government.

Not that the Cannabis plant itself cares about what governments think. From its humble roots as an aromatic herb growing in the wilds of central Asia, Cannabis sativa has not only continued to thrive in its natural habitat but has spread all over the world as a cultivated crop, finding its way into indoor closets and warehouses. It has even escaped cultivation to exist as a feral “weed” in ditches and fields in North America. People have taken advantage of this plant as a source of fiber, as a medicine, as an oil producer, as a food, and as a drug, and cannabis has taken advantage of people to care for it and propagate it.

Cannabis, like all “weeds,” is a plant that exists in relation to people. Our relationship with weeds is fraught; we resent the success that weeds enjoy in spite of our objections, so we have forgotten much of what weeds can teach us and we invent new ways to try and destroy them. In trying to rid ourselves of weeds we sometimes blindly contaminate our own water supplies with herbicides. But we might have fewer “weeds” if we learn to see how such successful plants can have a valued place in our world.

Many people would be surprised to learn that many of the “weeds” that populate our gardens were plants that we once cultivated in our gardens. Lactuca serriola, for example, which gardeners variously and inconsistently refer to as “wild lettuce,” “prickly lettuce,” or “Sow thistle” is the ancestor of the lettuce that’s for sale in the market. Not only is it edible, Sow thistle has more nutrients in it than “regular” lettuce. Lambsquarters, aka “dungweed” or “Goosefoot,” is an antique form of spinach. Stinging nettles, or Urtica dioica, is another “weed” that was imported here to the Americas from Europe as a food crop. French purslane, or Portulaca oleracea, is a common garden pest – until you learn to eat it! The Mexicans know this “weed” as verdolaga and esteem its use in the kitchen as a cooking green, like spinach. I’ve also enjoyed fresh purslane as a main ingredient in a flavorful, spritely Moroccan salad.

If more of us learned to use the weeds in our garden we’d have fewer “weeds” and a more diverse gardenscape. But weeds are perverse, temperamental and ornery. Besides being higher in vitamins and minerals than many of their more modern, refined, and esteemed cultivated cousins, many edible weeds are quite high in irony; I’ve been amazed to see that whenever I begin to make money by selling the weeds from my fields they tend to disappear from the rows.

The high nutrient value of weeds is not lost on the insects that feed on food crops. When I worked on Star Route Farm in the early 1980s my employer, Warren Weber, taught me to use some weeds as insect trap crops. Shepherd’s Purse, or Capsella bursa-pastoris, is a little weed in the Brassica family that would often germinate along with our rows of kale and broccoli. And frequently we would be plagued with wild mustards and wild radishes too, which are also brassicas, just as the kales and broccolis are. Warren said, “If we wait to weed out the kale and broccoli, the flea beetles will feed on them instead of our crops.” I observed that, time and time again, this was true. The insect pests preferred the weeds! So we would wait until the kales and broccolis were past their infancy and big enough to withstand the flea beetles before we cleaned out the “weeds” that the pests were feeding on, and our crops were happier for it.

When I was farming on my own and raising artichokes, I learned to leave a fringe of thorny, mean, milk thistle, or Silybum marianum, growing at the edge of the field, and they would tend to draw off most of the Artichoke plume moth, whose wormy larvae can bore into the tender artichoke buds. Then one day a visiting chef, Tiny Maes, who worked at Kokkari, a Greek restaurant, showed me how young Milk thistle plants can be used as a traditional, rustic, winter ravioli filling. Thistles, like so many other weeds, are forgotten foods

Besides being food crops and/or insectary crops, some weeds are valuable tools in monitoring soil health. Nettles will only germinate in soils that are very rich in nitrogen. Often you’ll find nettles thriving in abandoned corrals or fields where cattle or horses left lots of dung years before. When I see lots of nettles popping up I know that spinach, lettuce, and chard will all grow well, because they need lots of nitrogen to do well. But as the ambient nitrogen levels drop because the resource has been depleted then the nettles will disappear, and I’ll know it’s time to fertilize again.

Purslane in its wild “weed” form

Weeds can tell you when to plant too. Purslane, for example, only germinates when the soil is warm, so the first day I see a purslane sprout in the bed I know I can safely plant the seeds for a whole range of summer crops that would rot in cold soil. When the wild Tomatillo weeds sprout I know I can safely plant tomatoes. Other weeds can suggest crops to grow too. When there’s a lot of Poison Hemlock, or Conium maculatum, in a field you can bet that carrots will grow well there, as both plants are in the Umbellifer family. A healthy field of weeds promises a healthy field of crops (with enough work) just as a field where even the weeds struggle probably won’t bear happy vegetables without a lot of help.

Weeds are a problem, but they are not the worst problem a farm can have. Since they are almost inevitable companions if you don’t want to use herbicides, it can be good for a farmer’s mental health to remember their benefits. The days are getting longer, the soil is getting warmer, and because we had some nice rain, we’ll soon have a vigorous crop of weeds. Where it is convenient, I’ll wait as long as I can to turn the weeds under. Their roots reach down into the soil and bring up valuable minerals. Before they go to seed I’ll turn them under and treat them as a “cover crop.” Weeds will get the last laugh, I’m sure, but they can be useful jokers.

Tasty Mariquita purslane!

This week I’m putting Purslane or “vedolaga” in the harvest box. It’s hard to say this is a really a “weed” since I’ve grown it for several customers who have Mexican restaurants. Treat it like spinach and you’re off to a good start. It’s good in soups too. I used to grow it for Boulette’s Larder in San Francisco, and I bought the “Improved” French Purslane seed from a seed company but, irony of ironies, Chef Amyrll Shwertner prefered the wild, “weedy” form of the plant because it was smaller leaved and looked better on the plate. The Purslane seeds I’d bought became the weed!

© 2022 Essay by Andy Griffin

Photos by Andy Griffin

Simple Pleasures

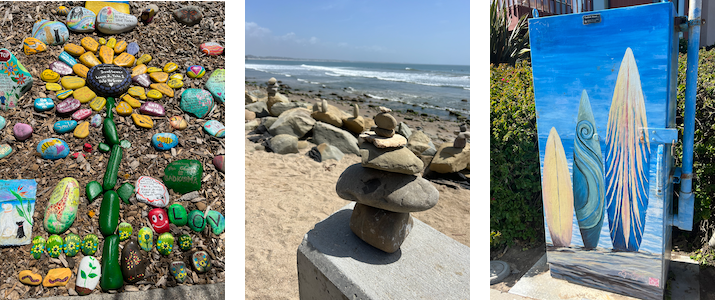

A beachside fruit vendor in Ventura, CA

With the tomatoes going into the ground this week, and with our first harvest share boxes for the Bay Area going out for delivery, Starr and I took a brief getaway down to Ventura ahead of what we hope will be a very busy season. It was a very mellow scene with warm weather, gentle breezes, a white beach, and surfers bobbing in the waves. We took a walk down the esplanade, and it was the typical zoo of Southern California humanity: tattooed women on unicycles, rainbow-clothed Deadheads selling bootleg swag in the shade of the palm trees, a gentleman taking his 6 foot boa constrictor for a walk on the lawn, and of course there was a fruit vendor.

We stopped at the fruit vendor’s cart and bought a serving of chopped, fresh, fruit. It felt very much like being back in Mexico. Mango, watermelon, cucumber, pineapple, cantaloupe, and jicama chopped and tossed with the juice of a fresh lemon and then dusted with red chile powder. As I watched the waves roll in and enjoyed the fruit, I had the thought that this simple preparation would be perfect with kohlrabi standing in for the jicama. Maybe even better, I thought, because the kohlrabi has the toothsome crunch of the jicama, and the white color which contrasts so pleasantly with the orange, red, and yellows of the fruits, but it has its own sweetness that makes it almost fruit-like.

When we have kohlrabi people always ask me, “How do I cook it?” My new answer is going to be, “Don’t.” And while we wait for fruit to come into season up here, kohlrabi can make a lovely salad all on its own, with maybe some chopped green onion. If you slice the kohlrabi, lightly salt it, and dress it with lemon juice, it tastes great. If you have the patience to put it in the fridge and wait a day, it tastes even better.

The lavender colored beans in your box are “Flor de Mayo,” or “May Flower” beans. In Mexico they would be flowering in May, but we planted our crop last summer and harvested them in late fall. We’ve saved the seed we’re going to plant so everything else is available to eat. They cook pretty quickly. A lot of people feel that it’s necessary to soak the beans overnight before cooking, but I never bother. These are so fresh they cook up fast and easy and soaking doesn’t achieve anything dramatic.

The lavender colored beans in your box are “Flor de Mayo,” or “May Flower” beans. In Mexico they would be flowering in May, but we planted our crop last summer and harvested them in late fall. We’ve saved the seed we’re going to plant so everything else is available to eat. They cook pretty quickly. A lot of people feel that it’s necessary to soak the beans overnight before cooking, but I never bother. These are so fresh they cook up fast and easy and soaking doesn’t achieve anything dramatic.

A bit of rain today and then some sunshine should be just right.

See you soon,

Andy and the Crew at Mariquita Farms

© 2022 Essay by Andy Griffin

Photos by Starr Linden

A Field with a View

Mt. Shasta looms over Redding, CA

What’s the stupidest thing you’ve ever done?

I’ve been busy in that respect but, with Mt Shasta as my witness, I have to say I’m lucky to be alive today. It happened a long time ago, but there are some “teachable moments” in my farce, so let me tell you the story.

Mount Shasta looms over much of northern California like Fuji over central Honshu: majestic, sacred, and iconic. When I was 16 years old I took my first job away from home working on a ranch just north of Shasta, and I never got tired of taking in the view. Because we’re about to start our farm’s harvest share program in the Bay Area for the 2022 season, and because I know I’ll be frantically busy for the next eight months, I decided to take a brief road trip up to Portland last weekend to visit my daughter, Lena, who works as a baker there. The drive north took me straight up I-5 and past Mt. Shasta, which stirred up a lot of memories.

My father was a botanist, and I recall him saying that when he was a grad student in forestry at UC Berkeley in the early 1950s the air was still clear enough to get a view of BOTH Mt Shasta and Mt Lassen on the horizon from Vacaville. It might still be possible on a rare clear winter morning after a rainstorm, but as I drove up the valley the other day I was past Orland and I still couldn’t see the mountains. I did see a kid “pulling a tarp” in a field of alfalfa that was being flood irrigated though, and I had to laugh. Been there, done that…

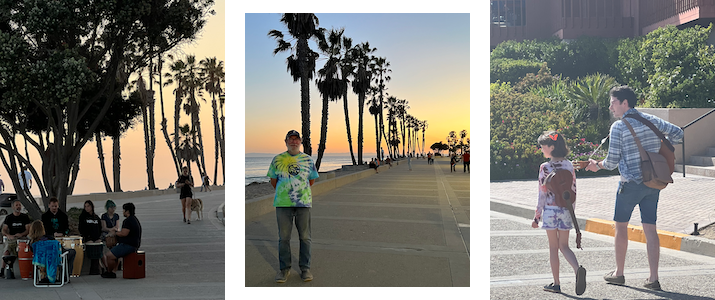

Drip irrigation tape wetting a sowing

On Mariquita Farm we have to be very conservative with water. We share the well with Hikari Farm, and the agreement we have with them is that Mariquita can water the crops every Monday, Wednesday, and Friday while they get to use the water every Tuesday, Thursday, and Saturday. And we only use drip irrigation, even to germinate the crops of greens.

But when I was working in the alfalfa fields in Northern California as a kid, we let the water flow across the landscape like there would always be plenty of rainy days. My father visited me on the Shasta ranch that summer and he shook his head in amazement when he saw me pulling tarps. “A crude, but effective method,” he said. “There are 5000 year-old hieroglyphics on stone walls in Egypt that show people irrigating this way.”

By “this way,” he was referring to the practice of flooding fields to irrigate them by using a series of ditches. It works like this: There’s a “Ditch Master” in charge of distributing the water of the district through a series of canals. When it’s your turn to receive your allotment of district water you need to be ready— it’s ALL the water you’re going to get, so you use it or you lose it, but you’re paying for it either way. Your ditches need to be clear of weeds or other obstructions, and you must make sure that no badgers or squirrels have burrowed holes in the banks which might leave tunnels that guide the water astray. And you need to have your stakes and tarps ready and in place.

When the ditch master turns the valve, the water rushes from the district canal down the empty ditch in a mindless hurry. It’s your job to discipline it. Every so often down the length of the ditch you need to have a sturdy log placed that spans the ditch and is firmly anchored in place. Beside this log you need to have a pile of sharpened sticks and also a heavy, canvas tarp. Before the water arrives at the first field you intend to irrigate you need to have already built your first dam. To do so you poke a series of sharpened sticks into the earth on the bottom of the ditch and then lay them up against the log that spans the ditch. Once constructed, the frame of your dam-to-be looks like ribs sticking down from a spine. Then you lay the tarp against the rib cage, from the top to the bottom, and the loose edge of the tarp is stabbed into the dirt with the point of the shovel. When the water arrives at the dam the tarp traps it, the dam restrains it, and so the water rises in the ditch until it overflows into the field.

As the water flows down the length of the field it is conducted and constrained through a series of “checks,” which are long, low parallel, raised mounds of earth—like speed bumps—which run the length of the field. While the irrigators are waiting for the water to adequately soak the ground they can usually use the time by building the next dams and tamping the canvases in place. That way, when it’s time to move the water they need do nothing more than “pull the tarp” from the upstream dam to release the water to flow further down the ditch. But you don’t “pull” the whole tarp at once—that would be hard to achieve due to the weight of the dammed water that pins the tarp to the wooden ribs—so you pull the top of the tarp down just a little so some water spills out, and then a little more, and a little more. Shenanigans can ensue, of course; your dam can break downstream if you release too much water too fast, or your tarp can get swept away in the flood as you release the water carelessly. Sometimes the ditch water has fish or snakes in it, or some other excitement. Back in the day in ancient Egypt an irrigator probably had to watch out for crocodiles. I had it lucky!

Once the ditch master opens the floodgates in a farm’s main ditch, the irrigators are busy until the water delivery contract has been fulfilled. On the day of “my greatest stupidity” we’d been irrigating around the clock for three weeks straight. We would do the short sets in the day and leave the longest sets for the night time so that we could get some semblance of sleep, but even at that I was getting up at 10pm, 12 am, 2 am, 4 am, and then we started the regular day at 6 am. So it’s fair to say I was very tired, and starting to get kind of dreamy in the afternoon. I had a field to irrigate that had over a hundred head of Brangus cattle in it. I set the tarp, let the water flow and looked south across the field at the dog and Mt Shasta.

The dog was always a help because she ran back and forth in front of the advancing water, so you could judge how far along the water had reached without actually walking the field yourself. And she busied herself snapping up the gophers that were driven to the surface by the flood. Sometimes she would even catch a fish. The water came out of the Little Shasta River and it had all kinds of creatures in it: turtles, crawdads, trout. And then Shasta. You can’t look at anything up there without having Shasta as a dramatic backdrop. I never got tired of looking at.

I’d been gazing at Shasta in a stupor for a while, and I heard a snuffling. I slowly looked about and saw that the cattle had gathered around me at some distance and were sniffing and ogling me, trying to figure me out.I stood there still as a post, and they slowly advanced as their curiosity overcame their fear. “I’ll bet this looks interesting from the air;” I thought to myself, “these cattle gathering around me in a ring. If I wait until they’re really close, then startle them, it would probably look like an exploding meat flower.”

And that’s exactly what I did: When the cattle got so close that I could smell their breath, I jumped up and yelled! They bolted in a panic. It probably did look like an exploding meat flower if observed from above. I certainly scared the shit out of them, and I had to walk through it as I went to pull my tarp and move on to the the next set. I’m lucky they didn’t trample me. And I feel bad about it now, because it wasn’t a nice thing to startle the cattle, and I do like cows.

By the time I got to Red Bluff I could see both Shasta and Lassen. It was a beautiful day. The weather has warmed up a lot, the soil is warm, and it’s time to plant tomatoes next week.

© 2022 Essay by Andy Griffin.

Photos by Andy Griffin

A Note from Andy

The pole bean patch has been laid out; gopher wire under the the ground, poles and trellis wire above ground. The first beans were planted last week. The white stripe you see is a row cover laid out to protect emerging seedlings from birds.

Hi All: We finally got some rain- two inches last night. The world feels fresh and beautiful but there are no puddles because the thirsty soil drank it all up. The frost seems like it has passed, so we’re busy planting the cold sensitive crops. Planting is going full speed ahead inside the green house too, and the young citrus orchard made it through the frosts of its first winter.

Left: The scarecrow we’ve put up to amuse the birds that fly inside. | Right: Kale and chard growing in the greenhouse.

Left: Our kitty, Tassajara, rubbing on an Assadas citron. | Right: Casha reflecting on the bean pods we saved for planting this spring before we shell them.

Akira and Moyu from Hikari Farm visit us as we work on our lavender labyrinth planting.

That’s life on the farm on a morning in spring!

© 2022 Captions by Andy Griffin.

Photos by Andy Griffin.

Magic Beans

Controversy was swirling at a recent school board meeting- “A REAL FOOD FIGHT!” read the headline of one local rag that covers civic affairs. But did the drama amount to a hill of beans? We investigate.

The trouble started when Ms Brooks read the classic text, Jack and the Beanstalk, to her kindergarten class. You remember the tale: Jack trades the family cow for a handful of magic beans which, when planted, grow up to the clouds. Jack climbs the beanstalk and discovers a castle occupied by a giant, etc. The kids loved the story, so the trouble didn’t start until they got home and told their parents what they’d learned at school that day. Many parents were outraged. Karen Feldenheimer was one of them.

“What are you teaching the kids?” she wanted to know. “There is no such thing as a ‘magic bean,’ because there is no such thing as magic. It must be a GMO bean! That’s evil!”

Carlo Avila, another involved parent, voiced the concern that this alleged “fairy tale” covered up the uglier aspects of Western colonialism. “How can we speak of ‘magic beans’ in an old Northern European fairy tale?” he wanted to know. “Prior to Columbus, the Europeans had no ‘beans.’ Sure, they had pulses, like peas, lentils, garbanzos, and favas, but true beans were only native to the Americas and so Jack couldn’t have encountered them in Pre-Columbian Northern Europe. Why do we whitewash the role that Native Americans played in developing so many of the world’s food staples?”

The cat inspecting the runner beans we saved for seed and will shell this week.

Jeanine Silva, a concerned mother of three, had a more nuanced perspective that she sought to voice, but perhaps the rowdy school board meeting was not the right forum. “True,” she said. “Pre-Columbian Europeans–even their Giants in the clouds–had no Phaseolus beans, and certainly they had no climbing beans like the Scarlet Runner beans, but they did have favas. And even though the favas don’t grow to the clouds they do grow tall!” She pointed out that the fava stems are hollow. “The ancient Egyptians believed that the spirits of the dead ascend to the clouds from the earth they were buried in by passing from the roots of the fava up through the hollow stem. Perhaps Jack ascended through a fava stalk? Can we agree it’s a possibility?”

“More evil magic!” yelled Karen Feldenheimer. “Let’s just teach the kids math!”

Frank Duval, the school’s oldest math teacher, was attending the meeting. He knew that Jeanine Silva was on to something but he felt insecure about supporting her in a public setting, as he was on the staff and couldn’t be seen taking sides. Frank was familiar with Pythagoras and taught the Pythagorean theorem as part of the regular curriculum. Frank also knew that Pythagoras had learned his math in Egypt. While Pythagoras is well known in geometry classes for his math skills, it is not today widely known that he also believed and taught his followers that it is evil to eat “beans,” and by “beans” Pythagoras meant favas. Why would eating fava beans be “evil” for Pythagoreans? It must have something to do with respect he had for the fava being the channel the spirits took to the afterlife, Frank reasoned. But he kept his mouth shut while the parents fought over beans. Sometimes people are not really interested in being informed or in questioning their assumptions.

The bean patch.

So where does that leave you and me? Are these “magic beans” that I’ve put in your harvest share box? I’d say, “yes and no.”

Even after 40 years of farming, I still think it’s magic when seeds sprout. The beans in your box are “Flor de Mayo,” or May Flower beans. We planted them last year in May when the danger of frost had passed. They are climbing beans, and we let them scramble up a trellis. They yield over a long season, and we saved the last of the crop last fall to be able to offer it to you this spring. Meanwhile, we’re already getting started on this year’s bean crop. Besides Flor de Mayo, we will be planting Oaxacan red beans and several kinds of pole beans.

In order to get a nice bean crop this coming fall, we have dug trenches and put down gopher wire to keep the gophers from eating the plants. On top of the ground we’ve put stakes and wire mesh for the vines to climb up. We will plant the seeds we saved from last year’s crop in about 10 days when the soil has warmed up. We are focusing on runner beans and other pole-type beans because they taste good and yield over a long season. They won’t grow to the clouds, but two of the varieties that we’re planting will form underground tubers, like potatoes, and sprout back from under the ground every spring. That’s magical too, as far as I’m concerned, and the repeat harvests will help amortize the start-up costs of laying out the wire and stakes.

When I was prepping the ground for the beans I turned up a bunch of rusty horseshoes. The field where I’m planting the beans was farmed with horses back in the day. My uncle told me that my great grandpa grew cucumbers there for Heinz, the pickle producers, back in the 1920s. I found five horseshoes so far and with that kind of luck we should have a wonderful bean crop to share with you. I guess the horseshoes are “lucky,” but they’re hard on the rototiller.

When I was prepping the ground for the beans I turned up a bunch of rusty horseshoes. The field where I’m planting the beans was farmed with horses back in the day. My uncle told me that my great grandpa grew cucumbers there for Heinz, the pickle producers, back in the 1920s. I found five horseshoes so far and with that kind of luck we should have a wonderful bean crop to share with you. I guess the horseshoes are “lucky,” but they’re hard on the rototiller.

Happy Spring!

From all of us at Mariquita Farm

© 2022 Essay by Andy Griffin.

Photos by Andy Griffin.

Big News

Hi Mariquita supporters,

We’ve been busy planting, weeding, and chasing the birds away from our baby seedlings and now we can plan our deliveries. We will begin packing our boxes in April. It’s always a bit of a mystery what will be ready in time for each week’s pick list, but there’s little mystery as to how we will go about distributing our veggies, fruits, flowers and herbs this year. Here’s our new setup:

For harvest year 2022 we are choosing to do staffed deliveries at a few of our pickup locations. This means that you will order as usual on-line to receive items for pickup. Then, on the delivery day, there will be a two-hour window for pickup from one of our team members at the pickup location. The pickup window for all these staffed deliveries will be from 4-6pm.

Look for additional items on the truck for sale. All sales can be done through Venmo, Zelle, cash or check (at pick up) at no additional charge and PayPal for an additional $2 per $25 spent.

We will continue our drop-offs at non-staffed Santa Cruz and Aptos pickup sites every other week on Tuesdays, starting March 15th. Those deliveries are starting, and we are taking orders now for the Tuesday, March 15th pickup.

CURRENT PICKUP SCHEDULES:

Santa Cruz and Aptos deliveries: These drop offs will begin on Tuesday, March 15th and will happen every other week.

Pick up windows: Santa Cruz – Noon-5pm and Aptos from 11-7pm.

Starting on Thursday, April 14th, we will be popping up twice a month at Piccino restaurant in the Dogpatch neighborhood of SF, Pick up window 4-6pm.

Starting on Thursday, April 14th, we will be doing a drop off delivery twice a month at our Los Gatos location, Pick up window Noon–8pm.

Starting on Thursday April 21st, we will be delivering twice a month to our Berkeley and Palo Alto Sites, Pick up window 4–6pm.

Once the shop pages open, the orders can be placed. All orders close on Sunday at 6pm for pickup the following week.

We are also planning to host a series of “Tomatopalooza” events and, new this year, we will be a holding several “Special Events” on our farm in Watsonville. Keep an eye on the newsletter for details!

Birds, butterflies and excitement are in the air and we look forward to bringing you a full basket of Mariquita love and vegetables this season!

Thanks,

Andy and all of us at Mariquita Farm

© 2022 Essay by Andy Griffin.

Photo by Starr Linden.

Get Ready…Get set…Go is coming soon!

The lemon arbor at Ganna Walska Lotusland in Montecito.

Life gave me lemons…But this isn’t an essay about me making lemonade. In fact, if I take personal responsibility for my circumstances, I should say, “Life gave me many privileges, opportunities, and learning experiences yet, despite those advantages, I chose to plant lemons.” More specifically, little by little, I’ve planted over 120 citrus trees, including 30 Meyer and 30 Lisbon lemons, plus an assortment of Bearrs limes, Thai Makrut limes, Yuzu limes, Ranpoor limes, Australian Finger limes, Buddha’s Hand citrons, Etrog citrons, and a scattering of Kumquats, Limequats, and orange varieties. The jury is still out as to whether or not the orchard was a good idea and on icy, winter nights I worry. If my fruit project doesn’t go sour I’m sure I’ll claim that I had a clear idea of what I was getting into and I executed my plan with precision and alacrity. In case my citrus scented dream ends in failure I’m already practicing my rationalizations. “I was seduced by art,” I will say. Or I can blame the Union Pacific Railway and Republican Party Politics. Or maybe I was doomed and my genetics betrayed me. Genetics are a good place to start.

After he stepped off the boat from Copenhagen and cleared Ellis Island my Great Grandfather Marius took a train to Minnesota because back in the late 1800s that’s where the Squareheads went. I’m told that after Great Grandpa arrived in Minnesota he wrote a postcard back home to the family. “This place is even worse than Denmark,” he said, referring to the cold wind, rain and snow of the upper Midwest in winter. It didn’t take Marius long to catch a westbound train for sunny California, and that’s how I came to be here on the Central Coast today. It’s not hot enough here in Corralitos to produce fine quality oranges, mandarines, or grapefruit, but we do enjoy a nice climate for lemons and limes. And, compared to the boggy, foggy little island in the Baltic that my family came from, this place is practically Ibiza. I’ve never been high on snow and ice so I have to imagine that whatever kink in his DNA that prompted my Great Grandfather to abandon the lands of his forefathers for sunnier latitudes got passed on to me and so I share his taste for the warm sun on my back.

My farmer friend, Annabelle, gave me a book by Helena Attlee titled “The Land Where Lemons Grow.” It’s a great book, well written, and full of history about Italy, food, the citrus industry and popular culture. There is even some practical information about growing citrus that is cleverly disguised by an entertaining delivery. The author is British and her book is infused with the same romantic attachment to the warmth of the sun that animated my Great Grandfather. When I visited the lovely gardens at Ganna Walska Lotusland in Montecito it all came together for me. There is a splendid lemon walk in Lotusland where trellised lemons cover an arched passage so that you are shaded by the foliage from the hot sun as you pass beneath. A luxurious display of beautiful yellow fruits hangs overhead and the refreshing scent entices you to reach for the lemons. Beyond the lemon arbor the Santa Ynez Mountains make for a magnificent backdrop. The scene looks for all the world like a page out of “The Land Where Lemons Grow” come to life. The old fashioned, colorful labels that fruit packers slapped on wooden crates back in the day come to mind too, with rows of green trees pictured in the foreground, bearing golden fruit, with blue skies overhead, dramatic mountains on the horizon, a Mediterranean style villa on the side. And there’s usually a frolicking young woman pointing to an inviting brand name like Sunny Cove, Wood Lake Nymph, or Sea Side.

The dreamy fruit box labels were no accident. During the Civil War Lincoln and the Republican Party sought to unite the west and east coasts by linking them with railroads. To stimulate the construction the federal government granted the Union Pacific Railway and the Central Pacific every other square mile of land along the proposed rail routes so that the companies had assets to leverage for loans from European banks. With the backing of the capitalists they began construction and to promote their new railroads they advertised the virtues of the western lands that they were opening up for development. The Egyptians may have invented math, the Greeks invented pizza and the Hebrews invented monotheism, but the Americans invented mass marketing, and in the promotion of the railways and the settling of the southwest no holds were barred and no exaggeration was too shameless. PT Barnum ought to be our patron saint. The lure of sweet oranges and tangy lemons- a virtual Garden of Eden simply waiting to be populated- was heavy juju for the poor, shivering northern Europeans and they came pouring out of Scandinavia, Germany, Poland, Ukraine and Russia. My great grandpa was one of millions.

As soon as my atavistic dreams (or illusions) of a sunny, citrusy, Edenic garden were awoken by Lotusland and Helena Attlee’s writing I began planting. An excellent citrus nursery, Four Winds, is just around the corner from my home so sourcing the plants was easy. I took note of the ground that I’ve got that is south facing so that it enjoys the most sun. I measured out the slopes because I know that cold air sinks, causing a slight breeze which can be just enough to keep frost from settling as it does on bottom ground. I staked the space, stretched out the drip tubing for irrigation and planted. I went in with my neighbor, Zea, from Fruitilicious Farm, and bought copious amounts of organic citrus fertilizer. I cloaked the trees with frost protection fabric when the cold threatened and I pruned and shaped the trees as they developed. Now the first harvests are here and there’s WAY more fruit than I could ever use. Things seem to be starting successfully so I need to make this essay about YOU making lemonade- or lemoncello, or lemon tarts, or lemony salad dressing, or all of the myriad of other recipes that feature lemons. And obviously, we haven’t stopped growing all of our other vegetable crops. The season is stirring to a start and we will send more specific information on our delivery schedule next week.

Meyer and Lisbon Lemons

Thanks,

Andy and all of us at Mariquita Farm

© 2022 Essay and Photos by Andy Griffin.

Photos of Fruit Packing Labels courtesy of Zea Sonnabend.

Maybe I’m Amazed

The very warm, almost hot, afternoons that we’ve been having this past week could lead a person to believe that we’re already enjoying summer. I was on restaurant deliveries in San Francisco last Thursday and I got my first request of the season for basil from a chef. Since I was double parked on California Street with a swirl of traffic around me I couldn’t take the time to explain that basil is a tropical herb that evolved in South East Asia. We must wait until the soil warms enough so that any basil seeds we plant feel at home and sprout with joy instead of sadly rotting away in the cold mud. As consumers it’s natural to feel the warm sun on our backs and feel aroused for a taste of basil pesto, but as farmers we can’t let our appetites dictate our planting schedule. It’s only February! Once the sun goes down the temperatures fall fast. As the sky darkens we see Taurus, the Bull, high in the sky. In April, when Taurus is sinking into the western horizon at sundown, we will know that spring is here and that we can safely plant basil outdoors without worrying about frost. But next week we will sow trays of basil in our greenhouse so that we can get a jump on summer by transplanting out little tufts of basil seedlings on April 15th.

Maybe Taurus, the bull, is on my mind because we’ve been creating a labyrinth on the farm and planting it with lavender, and we’re making real progress. The Minotaur, you’ll recall, was the monster with the body of a man and the head of a bull who was imprisoned in a labyrinth in Crete. Today we would say that, properly speaking, the Minotaur was imprisoned in a “maze.” The two words, “maze” and “labyrinth,” have been used carelessly or interchangeably at times in the past, but today we understand a maze to be a puzzling construction, full of blind alleys, dead ends, and troubling forks in the paths- like the maze that Theseus threaded his way through when he went to slay the infernal bull headed man. But a true labyrinth has but a single path. True, as you walk a labyrinth your path may loop around and appear to take you away from reaching the center, but if you keep going down the path, you will get to the heart. We are planting beds of lavender between the pathways of the labyrinth that we are constructing, and in time these plants will form a hedge. Last season my partner, Starr, harvested lots of lavender and dried it to use and sell and as this crop grows we will have even more. But why create a labyrinth?

Maybe I’ve just been planting crops in straight lines for my whole adult, professional life and I want to color outside the lines for a change? As a farmer I’ve always understood that farming is different than gardening. As I experience it, gardening is about beauty. Gardening is meditation. Gardening is art. Gardening is a release. Gardening is play. And farming is about money. Nobody pays a farmer to meditate, create art, play, or experience release. People need food at a price they can afford, so if you’re going to stay in business as a grower you need to take whatever measures you can to bring your crops to market at a price that will generate the sales you need to get the money needed to pay the farm’s bills. This reality is as old as God. If you read the Book Genesis you’ll see that we were kicked out of the Garden of Eden for the sin of eating the fruit of the Tree Of The Knowledge Of Good And Evil and condemned to farm. “Cursed is the ground for thy sake,” said God. “In sorrow shalt thou eat of it all the days of thy life; Thorns also and thistles it shall bring forth to thee….” etc. In April, when the basil sprouts with joy, so will the thorns and thistles in the field. Farming is work. Maybe I just want to play. Or maybe I’m amazed.

In Old English to amaze meant to bewilder or confound and the root word, “maes,” is cognate with our modern word “maze,” which accurately describes the devilish Cretan prison that confined the Minotaur. There is certainly plenty to be “amazed” about these days, from the bewildering climate crisis to our political dead ends to the smog of ignorance and disinformation that contaminates public discourse. If you live in an online world where you’ve had your life upended by stock market turmoil or the kinks in the supply chain, or if you’re working from home and sick of it, then a life outdoors, farming in the fresh air, might seem like a great alternative. But that would be gardening, lol… We farmers have had our lives upended too over the last several years of the Covid pandemic. Last year, for the height of tomato season, the packaging suppliers didn’t have cartons and we really had to scramble. Thank you all for returning the boxes after you canned your tomatoes- that REALLY helped us. By the end of last year’s growing season I felt pretty much out of gas, and I’ve looked at our labyrinth project as a therapy. Don’t forget, the difference between a maze and a labyrinth is that a labyrinth has a single path, even if it is convoluted, and if you stick to it you will reach the center. And who doesn’t need to be centered these days?

The Labyrinth has been a slow process because we can only work on it when we don’t have other, more pressing farm chores to complete, but we’ve been plugging away for some time. For our “staycation” the first Covid winter Starr, and I visited a number of local labyrinth constructions. Oakland’s labyrinth in the Sibley Volcanic Preserve was an inspiration, as was the labyrinth in San Francisco near the Presidio on the water. This past winter Starr and I visited a labyrinth in Houston, Texas, just down the block from the Rothko Chapel, and another in Tucson at the Arizona-Sonora Desert Museum. We came home energized to get back to work on our labyrinth, and the warm, dry weather has given us an opportunity to make a lot of progress. We’re hoping that sooner or later Covid will pass, and we can invite you to come visit the farm, walk the labyrinth, and enjoy the farmscape that your patronage and support is helping to create. And for any of you who don’t want to feed the spirit by walking in circles we’re still planting crops in straight lines to feed the body too. Onions, lettuces, carrots, greens and herbs are growing in the greenhouse already, and right now we’ve got tomatoes started in trays for transplanting out in April when the wintery Bull has left his nighttime pasture.

Our 2022 goal is to be up and operating a pop-up event each week starting in early April and to augment that outreach with a number of on-farm events in the summer and fall. Keep an eye on the newsletters and we will keep you posted on developments and opportunities.

Happy New Year, be well, and we will see you soon.

Thanks,

Andy and all of us at Mariquita Farm

© 2022 Essay by Andy Griffin.

Top photo of labyrinth by Starling Linden.

Row of photos of Oakland and San Francisco labyrinths, and photo of arugula in the greenhouse by Andy Griffin.

Creative Evolutions

Borders are interesting places. Yes, borders divide people into one side and the other side, but borders are also places where different cultures make contact. Misunderstandings abound along frontiers, but so do creative evolutions. The Pacific ocean has acted like a vast border but it has also been the connective medium between the Americas and Asia, and this week’s harvest box underscores that relationship. Take the shishito pepper, for example.

We think of the shishito as a “Japanese pepper” — I get my seed from Kitazawa Seeds, in Oakland, a company that specializes in Asian vegetable varieties — but a botanist will tell you that everything about peppers are American in origin, except the name. Columbus had investors who financed his voyages to the “Indies.” He couldn’t afford to disappoint the powerful people who placed bets on his dream. Vast profits were going to be realized by crossing the Atlantic from Western Europe to India and returning home with cargoes of Piper nigrum, or Black Pepper, deftly cutting the Muslim traders out of the spice trade by making their overland routes from Asia irrelevant. So when Columbus careened into seas and lands that were new to him, a new world devoid of even a single grain of Black pepper, he had to talk fast. The locals got called “Indians” and the spicy fruits that they cultivated got the name of “peppers.”

Habanero peppers

Back in Europe, the people were hesitant to accept this hustle and the new “peppers” only gained acceptance slowly, which is not surprising considering the ignorant and religious context of the age. Any plant not mentioned in the Bible could reasonably be defined and feared as “Satanic.” In today’s marketplace, we have a myriad of different kinds of peppers available, from the tame Bell pepper to the fiery Habaneros, but it’s worth remembering that every basic form of this widely variable plant had already been developed by the Native American farmers. Asian cooks didn’t have the same prejudices as their European counterparts and the new American “peppers” found a ready place in the kitchen. The Japanese are not known for their dependence on picante flavors and they adopted a mild type of immature, green pepper as their own, selecting and improving it to make it conform to their tastes, dubbing it the “shishito.”

Akahana beans

A similar dynamic occurred with the runner bean. Beans, like peppers, tomatoes, potatoes, sunflowers, corn and squashes, were originally developed by Native American farmers. The “old” world had pulses, like peas, lentils, garbanzos, and soy, but they did not have the Phaseolus beans like the Kidney bean, the green bean, or the runner bean. Compared to many other legumes, runner beans prefer a cooler environment to grow in. The cool highlands of Central America, from Oaxaca down through Guatemala, were home to a tribe of rambling, scrambling, climbing, vining beans now known as “runner beans.” The Scarlet runner bean earns its name by virtue of its brilliant scarlet flower. It has a white flowered cousin known as the white runner bean. These beans found favor among Japanese farmers due to the large size of their seeds and their mild flavor and velvety texture once cooked. The Japanese selected and improved the new American beans to suit their taste, and called the purple seeded form the “Akahana mame” and the white seeded bean the “Shirohana mame.”

Shirohana beans

Shirohana flower

Thank you for your support this season. We’ll be closing the farm down for a bit to rest, regroup, and come up with a new business plan. Work will not stop during our shut down, but Starling and I will be down on a border ourselves, visiting Organ Pipe National Monument on the Mexican border to see some cacti, dropping in on the Everglades to visit with family and see some alligators, and hopefully even venture out to the Florida Keys and the Dry Tortugas National Park to gaze out across the Caribbean and make plans for the future.

We wish you happy holidays and a healthy, peaceful winter!

We wish you happy holidays and a healthy, peaceful winter!

Andy and the Crew at Mariquita Farm