Letters From Andy

Ladybug Postcard

In Loving Memory

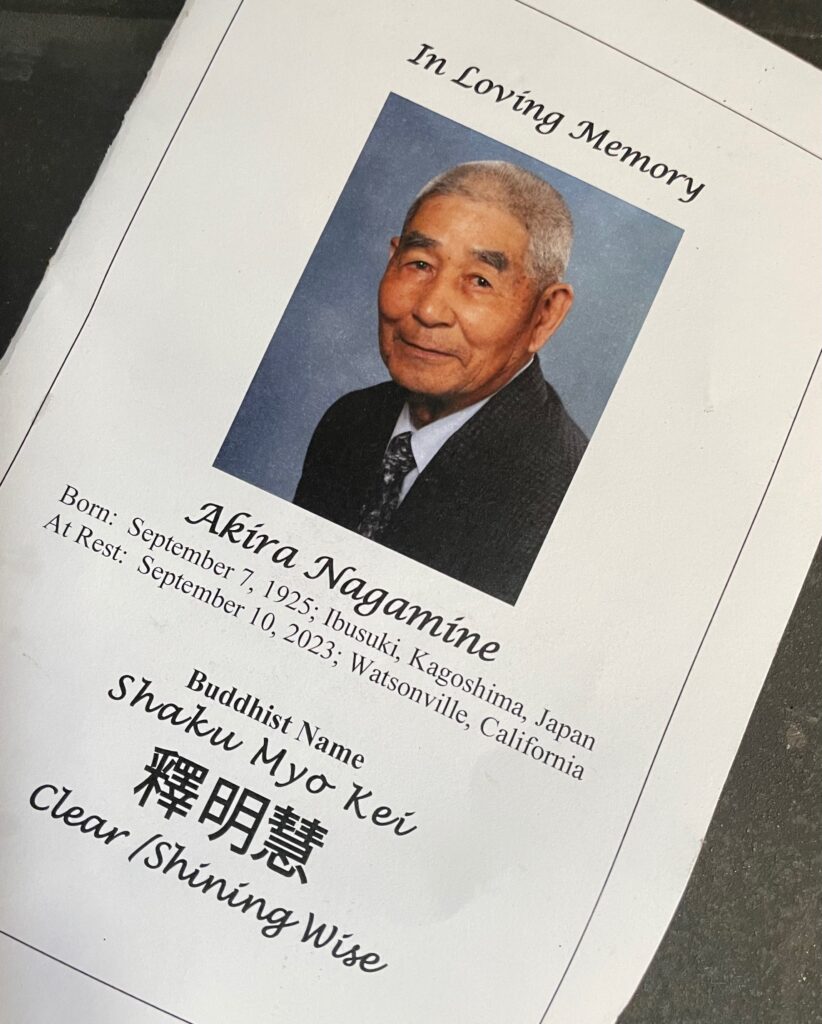

The sanctuary of the Watsonville Buddhist Temple was lined with huge displays of colorful flowers. People dressed in black filed in until the room was full. It was quiet. There was incense. There would be a chanting of sutras and the Dharma message would certainly be about the impermanence of all created things and the inevitability of suffering and loss. We were gathering together to honor a prominent local farmer, Mr. Akira Nagamine, who had just passed away at ninety eight years of age. While it can’t be a surprise when a very elderly person dies, there was still a sense of shock in the room. Mr. Nagamine had seen so much life, and was so relentlessly determined and energetic, that he seemed as much a force of nature as one of its creatures.

The sanctuary of the Watsonville Buddhist Temple was lined with huge displays of colorful flowers. People dressed in black filed in until the room was full. It was quiet. There was incense. There would be a chanting of sutras and the Dharma message would certainly be about the impermanence of all created things and the inevitability of suffering and loss. We were gathering together to honor a prominent local farmer, Mr. Akira Nagamine, who had just passed away at ninety eight years of age. While it can’t be a surprise when a very elderly person dies, there was still a sense of shock in the room. Mr. Nagamine had seen so much life, and was so relentlessly determined and energetic, that he seemed as much a force of nature as one of its creatures.

Here at Mariquita Farm we knew Mr. Nagamine as “Senior,” or “El Senor.” Over the past eight years I’d had the opportunity to lease several of his greenhouses on Hikari Farm for my own production, so we worked right alongside Senior and his crew. We even grew some of the same crops as Senior, like mizuna, shungiku, shiso, and Akahana mame. I’d keep an eye on everything Mr. Nagamine did, hoping to learn by example. I know he observed my practices and he’d be especially curious when he’d see me grow a crop he was familiar with but which I’d harvest or present it in an unexpected, or non-traditional manner, like harvesting tiny mizuna plants for green salads rather than waiting until the crop was large and robust and then bunching it. Senior was a traditional Japanese farmer- truly “Old School”- but his curiosity and interest in the world made him seem far younger than his years.

I’ll always remember Senior seated at his workbench in the packing shed, carefully sorting and bunching the “negi,” or Japanese scallions, that were one of his specialties. Most commercial farms have their workers wad green onions into bunches as fast as their hands can snap the rubber bands, but that was not Senior’s style, not “Old School.” Senior had a reverence for negi that were properly grown, harvested, and packaged. Negi are not “just green onions.” A properly grown spear of negi can take almost a year to produce and it might have a foot of pure, white, tender stalk under its display of deep, green leaves. And a proper cook knows how to utilize and appreciate every centimeter of the negi onion, from its roots to tips of the pointed, tubular leaves. I don’t want to put words into his mouth, but it’s possible Senior didn’t believe anyone under 60 even had the skills, appreciation, or wisdom to bunch negi correctly. At any rate, Senior bunched most of his crop himself, and I’m sure that it was as much a working meditation for him as it was a chore or responsibility.

One morning my once-upon-a-time employer, later business partner, and always friend, Toku Kawaii, called me up. She had a childhood friend visiting from Tokyo who would like to see a bit of the “real” California that lies beyond the freeways, malls, and convenience stores; could the two of them visit the farm?

“Of course!”

Toku and her guest arrived at the farm gate and I went to greet them. They stepped from their car, chatting in Japanese. Senior may have been 92 but he could hear plenty well when he wanted to. And he heard two women outside speaking Japanese, so he abruptly set his negi aside and popped out to see who had arrived. I introduced Senior to Toku and her friend and he was beaming. He welcomed them to Hikari Farm and asked them if they wanted tea and a visit to the greenhouse.

“But, of course!”

So, in due time, we entered the first greenhouse, a huge, glass enclosed space that Senior had planted out in orderly successions of his principle crops- Napa, mizuna, shiso, kabu, daikon and, of course, negi. The women admired the tidy crops in their neat rows and they enjoyed Senior’s animated answers to all of their questions. I can’t say I learned much from their conversation, because I can’t speak Japanese, but listening to the three of them speaking did remind me of Senior’s dexterity with language.

Mr. Nagamine was born into a farming family in rural Kagoshima, Japan, in the first part of the 20th Century, so Japanese was his birthright. But he could speak Mandarin too. In 1944, as a 19 year old Akira Nagamine was drafted in the Imperial Japanese Army and shipped off to the war in Manchuria. The war soon ended, but in the chaos of “peace” the Japanese soldiers in Northern China were abandoned to their fates as the Chinese Communists fought the Kuomintang. It would be eight years before he could be repatriated to Japan. During that time Mr. Nagamine lived by his wits, by his positive energy, and by his will. Senior Nagamine’s negi were tender to the core….but Senior was a very tough man. When Senior and his brother immigrated from Japan to America they found work first in the strawberries, so Senior learned to speak Spanish. They saved enough money up to buy their own farm and he learned English too,

When Toku, her friend, and I reached the beds of radishes, Senior asked his new friends a rhetorical question; “Do you enjoy daikon?”

“Of course!”

So Senior set to picking each of his guests a daikon root to take home. The first root he pulled was giant, but it had some unfortunate scarring from Cabbage root maggot, so he set it aside and searched for another. The second daikon that Senior pulled was 24 inches long, two inches wide, and pretty clean, but still, if you looked, you could see discoloration at the tip from root maggot damage. And the third root too displayed a bite mark or two, if you really looked. Senior reached for another daikon.

Toku could see where this was going and she made it clear to Senior that these roots that he’d already picked were spectacular and more than enough. Senior grudgingly acknowledged her concerns and stopped pulling roots, but it didn’t come easy. Before his later-in-life career as an organic grower of traditional Japanese vegetables, Senior had been a successful cut flower grower and shipper. Flowers can hardly help but be “pretty” but Senior always aimed at “flawless.” for his blooms, and he carried that baseline expectation of perfection into his life as a vegetable farmer. I’m not sure he knew the word “mediocre” in any language. In his own eyes he might have fallen short by gifting Toku-san a merely spectacular daikon, but the women had a grand time. Mr. Nagamine had a great time too, and I’m left with a treasured memory of a very pleasant morning with friends.

I’m glad I got a chance to get to know Mr. Nagamine. Sometimes I’d come into the farm in the morning and I’d be crabby because the wholesale prices were so crappy, or the weather wasn’t cooperating with my designs, or a pile of paperwork at home that I absa-f-inlutely didn’t want to deal with was waiting for me back at home, or my back hurt, or my tires were low,. And then I’d see Senior methodically checking his side of the greenhouse, frowning at the weeds until they wilted and coaxing his negi to grow straight and tall. “Holy cow,” I’d think. “I’m 63 and Senior has thirty five years on me and he’s not complaining; his stuff looks great, his customers appreciate his efforts and he has a good attitude. So shut up, Andy, and buck up. We live in a paradise so enjoy it while it lasts.” Serious respect!

So there was a Dharma message from the Reverend about the impermanence of all created things. “Every introduction will inevitably lead to a parting, to a “goodbye” if we’re lucky, to an unresolved sense of loss if we never get to say our goodbyes to our loved ones or make our peace with those with whom we had misunderstandings. Death and sadness are inevitable and every religion, every culture, has figured out ways to help people confront this reality.

I’m not a Buddhist so attending Mr. Nagamine’s memorial service was a learning experience for me. If anything, I’m a lapsed Lutheran. I can remember the Lutheran pastor talking once about religion and about how some people just want to treat the array of religious expression we see in a diverse place like California as though Ultimate Truth is a “smorgasbord” of sorts where we just pick and choose different practices to follow or beliefs to endorse as though they were so many “hot dishes” we could serve ourselves with.

“Yeah, that’s me,” I thought. I’m as Californian as the day is long and I’ve caught myself looking over the various religious convictions I’ve been exposed to and thinking, “nah- that looks like jello salad with mayonnaise,” or “yeah; I can swallow that.” What can I say? I’ve been exposed to diverse traditions and I was schooled in scepticism when I got a degree in Western Philosophy at UC Davis, so being a true believer comes hard. But that doesn’t mean I think that all spiritual expression is “jello salad.” No. Grief and loss are real and while we can’t ever change that we find ways to make beauty out of pain and we keep on plugging away. Day of The Dead celebrations are one way that some cultures have chosen to find beauty amidst grief. Following in the Mexican tradition you can see what we’re doing for the Day of The Dead, or Dia de los Muertos, by looking at our events page..

![]()

This year Starr and I have again created an extensive planting of marigolds as an exercise in farming, gardening, art, and meditation. Marigolds are appreciated in a number of religious traditions because of their rich color and pungent scent. With over 3000 tall marigolds planted around a huge lavender labyrinth the whole field is practically a shrine crafted from plants, but we’re putting together a small altar to honor the loved ones we’ve lost. This year we’re opening the farm up for a Day of the Dead, “Dia de Muertos” celebration in association with the “little bears” from Osito restaurant in San Francisco. You’re invited to come share a traditional celebration meal that Chef Seth Stowaway and the crew from Osito will put together on Saturday, October 28th. Come and walk the labyrinth, take in the amazingly bright and beautiful marigold planting, hear stories, and join in several traditional Mexican Day of the Dead activities like face painting, the gifting of sugar skulls, and the sharing of the Pan de Muertos. Maybe you’ve got a photo or memento that you’d like to contribute to the community ofrenda. Or pick some marigolds and take them home to fashion your own personal bright and aromatic altar. The farm is beautiful right now. Don’t miss out on your ticket to this fall event at Mariquita.com

See you soon!

Starr and Andy

Mariquita Farm

The work never stops here, and we welcome volunteers. We can especially use help weeding the labyrinth since we use no herbicides. During the rose season it’s great to have some help “Dead-heading” the roses. Right now it’s bean season so we’re threshing, winnowing, and sorting beans. Here’s the link to our volunteer signup. https://www.mariquita.com/friends-of-ladybugs-labyrinth/

As always, keep an eye on our website or subscribe to our newsletter for info on upcoming pop up tomatopallozas and events. https://www.mariquita.com/events-and-workshops/

Thanks, and we hope to see you soon.

© 2023 Essay by Andy Griffin

© 2023 Essay by Andy Griffin

Pop Up and Event Schedule

Sunflowers are SO COOL. Edible, ornamental , celestial Fibonacci equations playing out in the garden.

Upcoming Schedule for Tomato Pop-ups & Events

Note: The order page on our website for the Tomato Paloozas opens on the Friday a week before the pickup and closes on Wednesday at 10 pm.

TOMATO PALOOZA

SF, Piccino Restaurant on Saturday, Sept. 23rd. 10:30-12:30pm

TOMATO PALOOZA

Corralitos/Watsonville at Jett and Rose Sat. Sept. 30th 10:30-3pm

TOMATO PALOOZA

Berkeley, Sunday, October 1st – 11:30-1:00

FARM EVENT

Mariquita Farm, Oct. 7 & 8th Participating in the Santa Cruz County open farm tours visit our farm, sign up at Open Farm Tours

FARM EVENT

Mariquita Farm, Oct. 9th

Harvesting Culture Feast – 4-7:30 pm. Tickets at Openfarmtours.com

TOMATO PALOOZA

Palo Alto, Saturday, October 14th- 10:30-12:30 pm.

TOMATO PALOOZA @ Earthquake Block Party

SF, Richmond Dist., Tuesday, Oct. 17th 4:30-6:30 pm.

TOMATO PALOOZA

Piccino Restaurant, SF, Saturday, October 21st

10:30-12:30

FARM EVENT

Santa Cruz, Jack O’Neil Restaurant/Dream Inn,

Jack O’Lanterns, Vines, Bites & Brews

Thursday, October 26th,

6-9 pm. Tickets on the Dream Inn website

FARM EVENT

Mariquita Farm, Saturday, October 28th, 3-7 pm.

The Ladybug and the Little Bear play in the flowers…

Join Mariquita Farm and Osito Restaurant of SF for

Traditional Dia de Los Muertos dinner and activities at Mariquita Farm

Space is limited. Get your tickets for this special dinner event here.

Zucchetta Rugosa being harvested. We will have these heirloom Italian Butternut squash for casual sale by the piece.

A Taste For Pachamama

The bedroom slash squash storage warehouse. If I leave the squash in the field the squirrels will eat them all. Here they are safe.

Five school girls followed me down the steep cobbled street at a distance, giggling, until one of them got up the nerve to dash past, turn, and confront me. “Would you please come to my house for tea?” she asked.

Her friends crowded around. They were thirteen or fourteen years old, dressed alike in the matching skirts and dark sweaters of their school uniform and their hair was tied back in long black, glossy braids. Having gotten over their initial shyness, they made the quantum leap to boldness and began pelting me with questions; “Are you German? Why are you here? Are you married? Do you believe in God?”

“Shut up,” barked the boss girl. “He’ll answer our questions one by one in a proper interview.”

“Why, yes,” I replied. “I would be delighted to come to your house for tea.”

The girls went into a brief huddle, and arrangements were made. One girl wrote out the address on a piece of notepaper, another girl drew a map, and a third girl left to get some cookies. “We’re looking forward to visiting with you at 5:30,” they said. “Please come.”

They didn’t need to worry. I’d been traveling alone in Bolivia for a month. I was just coming back to town from a walk in the mountains when the girls stopped me. It was late in the day and windy. I was cold and tired. Hot tea sounded nice. These bronze faced girls were bright eyed and charming. I was curious to see how they lived.

I scrubbed up at the room where I was staying and found a clean shirt. The town was tiny, so the girl’s street wasn’t hard to find. I made sure to knock on the door precisely at 5:30, and the leader of the posse welcomed me into her home. I entered a small living room with a sofa against one wall. My young hostess motioned for me to sit. Her friends brought in chairs from the rest of the house and we all sat around the edges of the room, facing each other, with our backs to the walls. Hanging from the walls was a framed image of La Virgen del Socavón, a clock, and a calendar with a shiny picture of the Swiss Alps. The Alps looked like the painted backdrop for a toy train layout compared to the sullen peaks of the Andean Cordillera that loomed up behind the street outside. And rising up in the middle of the floor, almost filling the room to the ceiling, was a conical mountain of freshly dug potatoes.

The girls poured cups of mate de coca and passed around the cookies. They each spilled a ritual drop of tea onto the floor. “A drop for Pachamama,” they recited, “a drop for me.” Then came the flood of questions. “Are you German? Why are you here? Do you like our town? Have you been to Miami? Are you married? How many children do you have? How much money do you make?”

“One at a time,” I pleaded. So the girls slowed down and introduced themselves. Their homework assignment was to study a foreign country and write a report. I looked German. They would get good grades and extra credit for interviewing me. Formalities observed, the girls got down to business and I swung at their questions almost as fast as they pitched; “No, I wasn’t German. Yes, I liked Bolivia. No, I didn’t have children yet, although yes, I was already 32 years old and I did want a family, but no, I hadn’t met the right woman yet, and yes, I’d been to the Miami airport, but no, I don’t live there, and anyway California is nice too.” I even tried to ask the girls a few questions of my own.

A wheel barrow load of Rugosa squash. This is an heirloom Italian variety of butternut squash. I will save the best examples of the breed for seed and sell (or eat) the rest when they’ve cured.

“How come you keep the potatoes in the house?” I asked.

“Because they’ll freeze outside or someone will steal them,” the girl said.

“In California I’m a farmer and I grow potatoes,” I said.

“Oh, everyone grows potatoes,” another girl said. I suppose she was right, at least in her world. “Besides,” she added, “you’re not a farmer; you are an ‘ingeniero agronomo.’ Germans aren’t farmers and farmers are too poor to travel.”

An ‘ingeniero agronomo” would be an agronomist or agricultural consultant. I understood where she was coming from; in rural Bolivia people as white as I am are not farmers. And farming there isn’t a trade people chose to do the way I decided to “become” a farmer; Their parents were born into a life on the land when they were born on to this planet and alternative existences seemed foreign and fantastic. And who would choose to be a farmer and labor outside? Their world was harsh. In the Andes the day may dawn icy, but by mid-morning the sun can be hot on your back. After sundown the temperatures drop again, until your hands and feet are numb. The atmosphere is thin and the air is dry. The sky overhead is deep blue by day, and by night it is jet black and sparkles with majestic drifts of stars. Outer space seems close.

Most people in Bolivia live on the Altiplano, which means “high plains” in Spanish. The Altiplano is high– the altitude ranges from 9,000 feet above sea-level to around 14,000 feet– but the land is nothing close to being as flat as its name implies. The daily extremes of temperatures in the Andes have prompted a number of plants to evolve tuberous growth habits. A tuber is a swollen, underground stem that stores up energy so that if a “killing frost” burns off all the foliage above the ground, the plant still has enough life protected under an insulating mantel of soil to sprout again. The concentrated sugars and starches found in tubers have made a number of them important food crops. The sweet potato, for example, is a tuberous morning glory from Peru that’s now cultivated all over the world. Andeans also cultivate an edible tuberous oxalis, called oca. Potatoes are tuberous nightshades that evolved in the Andes, and they are cultivated there in great profusion.

An heirloom bean from Oaxaca that I’m growing out for seed. This type is typically eaten fresh, like a green bean.

While we find just a few varieties of potatoes on our supermarket shelves, a farmer’s market in Bolivia has potatoes of every imaginable shape and color heaped up for display. Little marble sized potatoes are piled up next to long, skinny ones and big round ones in colors ranging from blues, reds and purples to yellows, whites and browns. The different kinds of potatoes were not simply appreciated for their rainbow of “decorator colors.” Each kind of potato had its own unique attributes; some were more drought resistant, so if there was very little rain they might produce a crop, even when the other kinds didn’t. Some breeds of potatoes were more disease resistant than others, or stood up to storage better, or tasted especially good in certain dishes. There is a logic behind their rainbow of potato varieties, not just a fetish for novelty.

Bolivian farmers have turned the extreme climatic conditions they must contend with to their advantage, and they use Mother Nature’s mood swings to preserve their harvests for the hard times they know lie ahead. Potatoes are cut into pieces and laid out on rocks under the sun to dry, while the farm dogs prowl and bark any marauding crows away. At night, any residual surface moisture that sweats out from the potato chunks is frozen into a spiky beard of ice crystals, which evaporate in the morning sun. After a few days of this treatment, the potato slices are essentially freeze-dried. These black leathery potato chips are called chuño, and can be kept without spoiling almost indefinitely. Chuño is an acquired taste, but when you get used to it, it’s earthy and satisfying in stews and broths.

Our cat meets a wild turtle in the squash patch. She was curious, the turtle was not. It al;l turned out well.

Half the people I met in Bolivia talked of making their way to Miami. But among traditional people, it is still considered polite to thank the Earth Goddess, Pachamama, for the blessing of food. Even as the Virgin of the Mines looks down from the wall, the people will spill a drop of their beverage or let a crumb of their food fall to the ground before taking a drink or swallowing a bite. “A taste for Pachamama,” they’ll murmur, “a taste for me.” I heard this phrase so often in Bolivia that I began to notice the people who didn’t give thanks for what they had. Spilling drinks and food makes for sticky floors on buses and in public places but in the absence of any SPCA, giving “tastes” to Pachamama also keeps skinny, stray Bolivian dogs alive. Bolivia can be a tough place, but the habit everyday people have of giving “thanks” lends a hard and austere country a grace and humility that the populations of affluent countries can only aspire to.

I don’t think I ever convinced the young ladies that I wasn’t German. I answered some questions about life in California and had them laughing, even if they were disappointed that I didn’t live on a sugary, white sand beach with Gloria Estefan Y Miami Sound Machine.

When the tea party was over my hostesses thanked me profusely for helping them with their homework.

“Encantado,” I said, as I negotiated around the pile of potatoes and headed for the door. “The pleasure was mine.”

Alache in flower with a green seed. This is a Oaxacan potherb that is used to thicken broths in much the same way as okra (a relative) is used to give body to gumbo. I love how the seed looks like a Dharma Chakra.

Victoria cleaning beans. We do the work by hand because we’re too small scale to make machinery much of an option.

The work never stops here, and we welcome volunteers. We can especially use help weeding the labyrinth since we use no herbicides. During the rose season it’s great to have some help “Dead-heading” the roses. Right now it’s bean season so we’re threshing, winnowing, and sorting beans. Here’s the link to our volunteer signup. https://www.mariquita.com/friends-of-ladybugs-labyrinth/

As always, keep an eye on our website or subscribe to our newsletter for info on upcoming pop up tomatopallozas and events. https://www.mariquita.com/events-and-workshops/

Thanks, and we hope to see you soon.

© 2023 Essay by Andy Griffin

Pop Up and Event Schedule

The first of this season’s marigolds. I planted several thousand plants.

Mariquita Farm

Tomato Palooza Pop-up Deliveries

&

Special Fall Farm Events

Dear Friends and Long Time Supporters,

There is still confusion about our delivery schedule. We are no longer creating Mystery Boxes this year, but we are doing Tomato Palooza Pop-ups and Special Events!

The way Tomato Palooza Pop-ups work:

Each week on Friday we are posting a pop-up event on our website. You have until the following Thursday at 9am to order the items we are offering on the order form for Saturday delivery that week.

1. This week we are taking orders for Los Gatos, order window will close on Thursday September 7th at 9am, and delivery will be on Saturday, September 9th.

2. On Friday, September 8th we will be taking orders for Berkeley, order window will close on Thursday September14th at 9am for delivery on Saturday, September 16th.

3. On Friday, September 15th we will be taking orders for SF, Piccino Restaurant in the Dog Patch area, order window will close on Thursday, September 21st at 9am for delivery on Saturday, September 23rd.

4. On Friday, September 22nd we will start taking orders for the Corralitos/Wastsonville (Santa Cruz County) area order window which will close on Thursday 28th at 9am for delivery on Saturday September 30th. We will also be doing an Olive Oil and Tomato tasting at this event which will be held at the Jett and Rose boutique on Freedom road at 2905 Freedom Blvd, Watsonville CA. next to Alladin Nursery. Belle Farms (Olive Oil) whose oil we have been carrying for many years will join us!

NOTE: We will be posting additional Tomato Palooza dates as the locations are clarified and the produce becomes available.

A few upcoming events in October to put on your calendar, with opportunities to visit

Mariquita Farm:

1. Saturday, October 7th, Sunday, October 8th.

We are one of the featured farms on the Open Farm Tours in Santa Cruz County. For a small fee you can visit Mariquita Farm along with other near by farms. Go to Openfarmtours.com for more information and tickets.

2.We are also the host for the October 9th dinner from 4-7:30pm, “Harvesting Culture Feast” sponsored by Edible Monterey Bay Magazine.

3. Thursday, October 26th, we will be part of the

“Tasting of Santa Cruz” at the Dream Inn. More details will follow.

4. Saturday, October 28th, We will host a special dinner with Chef Seth Stowaway of Osito Restaurant in SF for Dia De Los Muertos (Day of the Dead) celebration with a Marigold u-pick, face painting, an alter and more. More details will follow.

5. Look for our Marigold U-pick announcement September/October to be determined with details to follow.

Victoria cleaning beans and sorting the stray Shirohana Mame out from the Akahana Mame. Shirohana mean “white flower” and Akahana means “red flower.” The color of the flower is a clue to the color of the eventual bean it produces.

You can pre-order for the our upcoming Los Gatos pop-up here https://www.mariquita.com/tomatopalooza-popup/

A “Slow” Recipe For Polenta

These corn plants have to be 10 feet tall- or more! I’m 6’1″

Here’s a “Slow Food” recipe for Polenta: I start by planting the corn.

Actually, it was my friend, Annabelle, who started the recipe for me by giving me some heirloom “Otto File” corn seed that she collected when traveling through Italy a number of years ago. “Otto File” means “eight rows” in Italian, and each ear of Otto File corn does display only eight rows of golden kernels. While other varieties of corn might be be more productive, Otto File is the “go to” corn for real, old-school polenta. Since I had Italian restaurants eager to make their own polenta “from scratch,” Annabelle’s gift of the correct seed was well timed and much appreciated. We planted the seed and grew it out for 3 years, saving only the best, longest ears of each year’s harvest until we had enough quality seed for a commercial scale planting. If you want to plant your own patch of Otto File corn all you need to do is buy a pound of seed from us at our next pop-up and save it to plant in the spring instead of milling it up to cook.

If you are going to make polenta, know this: “Store bought” polenta is “shelf-stable.” That is to say, each kernel of corn in store-bought polenta has been cracked and “de-germed.” The “germ,” or that embryonic part of the seed that germinates, has been mechanically removed and processed to make other, value-added products. When you make your own polenta from the corn meal you grind yourself you will probably not be able to (or want to ) de-germ the corn before grinding it up. The downside of grinding whole corn is that, once ground, the fresh ground meal will not hold up for as long as the industrial corn meal that has had the hearts removed. If you buy our corn to make meal from take care to grind what you intend to use promptly or the meal will eventually spoil. The upside of grinding your own “whole grain” corn is that it will be much richer and more flavorful that store bought polenta meal BECAUSE it is whole grain.

A bowl of shelled “Otto File” corn. I grind it “as is” and it seems to work out fine.

I like a mix of fine and coarse ground cornmeal for the most toothsome and interesting polenta.

To grind the corn into meal I use a Vitamix food processor. No, I am not an influencer who is going to profit from brand promotion. I find that three, separate 15 second pulses on the “smoothie” icon works out to make the best meal. To my taste, a blend of finely powdered meal with some larger chips or pieces of corn makes for a more interesting texture. I generally pass the meal through a sieve at least once to remove any really large pieces of corn that may not cook at the same rate as the rest of the meal. If necessary, I will re-grind the biggest pieces one pore time before preparing the polenta.

This is the polenta “mud” that I stir into the boiling water- SO much easier than letting a thread of dry grain trickle into the boiling water.

Marcella Hazan, the quintessential Italian Grandmother and the author of “Essentials of Classic Italian Cooking” recommends a ration of seven cups of water to one and 12/3rds cup of corn meal for perfect polenta. I’m not going to argue with her, but I always keep a tea kettle of hot water nearby when I’m cooking polenta so that I’m ready if I need to add more water. Think about it; polenta really only has four ingredients; corn meal, water, salt…….and time! If you want to cook a pot of polenta for a long time you will be rewarded with a richer flavor and a more velvety texture. Marcella cooks her polenta for 45 minutes but I like to cook mine for six hours.

A tray of hot polenta cooling in a baking pan. Even relatively liquid polenta will “set” well iin an hour or so f it has been cooked for a long time.

Once I have my pot of water boiling I add a pinch of herbal salt to the water. Then I stir a big spoonful of “corn mud” into the roiling water. Once the water is at a boil again I add another big spoonful until I’ve put all the meal into the water and the water is boiling again. Then I turn the flame down so that that polenta is barely bubbling. I’ll come back and stir it every 15 minutes or so but, basically, the idea is to let the polenta cook and cook and cook and cook SLOWLY. You may notice that the level of cornmeal gradually drops in the pot over time. I will add a dash of hot water if I feel like things are getting too thick too quick, but I usually just leave the pot to slowly bubble away.

Slices of polenta are perfect fried or baked. I like to get the polenta squares crispy on each side while keeping them moist and tender inside.

Our cat, Samson, enjoys the cool of the corn patch.

After five or six hours of slowly bubbling away I feel like the polenta is ready. I’ll pour the hot, soft polenta into wide ceramic casserole dishes and let it cool at room temperature. Once it is cool the polenta will congeal into a substance thicker than jello, which can be easily sliced and baked or fried. I like to fry the polenta in long, thick rectangles, taking time to turn each piece so that it is gilded and crispy on each side. If you wanted to you could fry up little tiny squares to use as croutons in a salad. I like my polenta served with a sauce as though it were a pasta. I always make a huge batch and freeze half of it so that I can whip up some polenta even when I don’t have time.

Setting up for the Corralitos Farm and Garden Market

We are in the middle of pop up season. This coming Saturday we will be in Los Gatos. In the weeks to follow we will return to Berkeley, San Francisco, and Palo Alto, as well as popping up here in Corralitos at the Sunday Farmers Market. We will be featuring lots of tomatoes, tomatillos, herbs and flowers, but we will also have Otto File corn for sale. Keep an eye on our newsletter for updates. You can pre-order for the our upcoming Los Gatos pop-up here https://www.mariquita.com/tomatopalooza-popup/

FIELD OF FLOWERS

Our first marigold of the season. The variety is called “Chedi.”

Let me start with a simple disclaimer; I do not intend in this article to promote, dispute, or ridicule any religious faith or tradition. Nor do I have any religious authority or aspirations to speak for god, or the gods. My only interest is in sharing what I’m learning about how to grow marigolds. It’s just that you can’t do much research into the interesting ethnobotany and Linnaean taxonomy of the marigold without soon becoming enmeshed in the theories, traces, and rumors of the divine. And that’s on top of the obvious misdirections and dead end paths that have been provided by marketing experts. The “African Marigold,” for instance, is not from Africa. We’ll get to that, but first let’s deal with our first Divinity.

In the early 1990s the Virgin of Guadalupe was said to have made a presentation in a grove of live oak trees in Pinto Lake County Park, here in Watsonville. An impromptu shrine grew up around the site. Predictably there were howls of outrage from Constitutionalist activists who were offended by a religious site being hosted on public property, but they soon got bored and went away. The shrine became part of the local landscape. Nowadays Mary’s oak tree no big deal, and soccer teams ritually visit the grove to be blessed by a Padre at the outset of the season the same way that a priest goes down to the harbor in Monterey to bless the fleet of fishing boats before they venture off into perilous waters. But while the “Just say ‘No’ to Mary in a public space” people were still squared off against the folks leaving flowers (AND CANDLES!) at the foot of the Virgin’s oak tree I took time to talk with the people on my farm crew about the controversy.

The fog helped the work of planting the field by making the work more comfortable.

“What do you think about la Virgin de Pinto Lake?” I asked Ramiro Campos. “Are you surprised that there was a presentation there, so close to where we live?”

“Well, no,” he replied. “Mary goes everywhere.” And he pointed to a random scattering of calendula weeds blooming along the drain ditch at the edge of the lettuce field where we were workingwith their cute, little, orange-yellow flowers glowing in the green grass.

I was puzzled.

Ramiro laughed. “The grandmas say that marigolds sprout along every path the Virgin takes.”

I laughed too. “She gets around!” I’d seen these so-called “marigolds” growing on disturbed ground on every farm I’d worked on all around California, usually popping up from late winter to early spring, and I recognized them as the wild cousins of the larger Calendulas that we often grew as edible flowers for the restaurant trade.

“It’s said that the Virgin walks the Earth at night and leaves gold coins in her wake for the poor to gather. “Mary’s ‘gold’ is easy to find, but hard to spend.”

Two years ago Starr and I visited friends in Texas who have a flower farm. https://www.texascolor.

The marigolds after one week in the ground.

I read up on marigolds in the off-season and discovered that the heavy scent of the African marigold is known to repel mosquitos. We’ve got a swampy canyon on the farm below our house that can host mosquitos in a wet year, so planting an aromatic boundary to the field seemed like a good idea. And it was fun to learn that the “African marigold” is from Mexico. Before the Columbian exchange, the marigolds that were used in Indian and Buddhist religious ceremonies were the same small flowered, cool season, calendula type, Old World “marigolds” that were appreciated in European Catholic traditions. But once that Spanish treasure galleon shipped into Manila from San Blas, Mexico, the “East Indies” discovered that these “new” marigolds from the “West Indies” thrived in their warm, tropical conditions. And the “new world” marigolds were everything the old ones were, but bigger, brighter, and heavily perfumed. Frank Arnosky gave me the information on the best varieties of Tagetes marigold for sacramental purposes that come from seed companies in Thailand, and I was off and running.

The south facing field we have on our home ranch seemed the best place to situate a crop of flowers. The field is sheltered, flat and gently sloped, so it would be easy to work and the soil would drain well. The first step was to plant a cover crop in the fall ahead of the first rains. I chose to plant a blend of oats, vetch, winter peas and barley to cloak the soil from heavy winter rains. And rain it did! We stopped counting at around 60 inches. We did have some erosion from the unexpectedly heavy-and early- rain, but the young oats and barley kept most of the silt in the field and I was able to turn the cover crop under in late april. The next step was filling trays with seed. I wasn’t in a hurry; if you want to have a nice marigold crop in October and November you should plant it in the field no later than July 25th. I had my plants ready to go right on time.

The marigold field this morning.

I rototilled up the first curved bed with the tractor and laid out a single line of drip tape. The marigold field embraces the circular lavender labyrinth that Starr and I created, so no row was ever going to be straight. Once the tape was soaking the row I used the tape itself to measure out where I would put each plant. The high flow drip tape that I use has an emitter every six inches, so I could use the spreading stains of wet earth around each emitter to mark where to put the tiny seedling. I planted well over two thousand plants, one every 18 inches. When I’d finish one row I’d start another. It took me a number of days to finish, but I liked working in the fog at dawn because the cool temperatures were best for the tender, young plants. Now, after a thorough weeding, the plants look strong, happy and healthy. We’ve even got the first blooms showing on a trial bed I did a few weeks earlier than the main crop to test the vitality of the seeds.

Starr is drying some of the blooms. Here you see the three colors of “Chedi” marigolds.

When I first met Starr 5 years ago she was making tiny little shrines for people using Altoids Mint containers. Her shrines reminded me of similar tiny “to go” shrines I’d seen in little markets in Ecuador and Bolivia but they were uniquely American with a riot of different cultural elements. If you are a surfer she can make you an oceanic shrine, if you’re a Goddess worshipper she can make you a goddess shrine. If you are struggling in the ganja business she can make you a shrine that speaks to those concerns. And as we looked at the field we thought it would be interesting to make the entire field into a shrine of sorts, celebrating all the plants and creatures that make up a healthy, diverse, and beautiful farmscape. For her, it would be a way to mix her passion for gardening with her interest in making shrines and to do it on a scale that you could see from a plane. For me it was an opportunity to take what I’ve learned about growing plants on a commercial scale but to bend all the straight lines and make the effort as much about beauty as about productivity.

Come down and see what we’re creating when we do our Marigold U-Pick this year. Keep an eye on our newsletter and on the website for dates and details.

We don’t just grow marigolds either. Beside the milpas of corn, squash and beans that we have on the farm, and the beds of herbs we are also cultivating a wide range of cut flowers. My favorites are the zinnias, which happen to come from Mexico originally, just like the marigolds. Starr is partial to her collection of Dahlias, and we both love the sunflowers. Starr will be bringing bouquets to all of our farm pop ups. And speaking of which, we just added more tomatoes to this coming weekend pop up on Ross Road in Palo Alto. The warm weather is helping bring the crop on, late but welcome. Look to our sales page to see where inventories are at and order some before they’re all gone!

On the 30th of September we will be doing a pop up at Jett & Rose in Corralitos with our friends from Bella Farm Olive Oil. Details TBA.

The work never stops here, and we welcome volunteers. We can especially use help weeding the labyrinth since we use no herbicides. During the rose season it’s great to have some help “Dead-heading” the roses. Here’s the link to our volunteer signup. https://www.mariquita.com/friends-of-ladybugs-labyrinth/

Thanks, and we hope to see you soon.

© 2023 Essay by Andy Griffin

Mariquita Farm Pop Up Schedule for Tomato Season 2023

Hi Everybody: Tomatoes are ripening as I write these words to you. As our harvest permits, we will be selling our tomatoes at a series of pop ups around the Bay. The season arrived late this year, but the plants are sound, healthy, and we are hoping for good harvests. We have a rainbow of cherry tomatoes planted, plus dry-farmed Early Girls, Piennolo, San Marzano and Heirloom tomatoes We will announce each sale and post what we can confidently offer for pre-sale on the Friday morning eight days before the sale date to give everybody (including ourselves) time to plan. We intend to bring extra crops to the pop-up for walk-by sales and time, labor and harvests allow, as well as a range of dried herbs, fresh flowers, citrus preserves, and other farm goodies. We may add dates if time and harvests allow. Keep an eye on our website and on your “in box.” If you don’t hear from us check your filters in case the algorithms think that we’re selling spam instead flavorful tomatoes, herbs, and flowers. Subsequent notices will give updates and additional information as to times of day, quantities and varieties of tomatoes, but here’s the schedule as we see it now:

August 19 Corralitos at Alladin’s Nursery at Freedom Blvd and Corralitos Road

August 26 Piccino Restaurant in San Francisco’s Dogpatch

September 2 Palo Alto off of Oregon Expressway on Ross Road

Thank you, and we hope to see you soon! Andy & Starr

And don’t forget, Starr is at the Corralitos Farm and Garden Market which is held each Sunday from 11 to 3 in the parking lot of the Corralitos Cultural Center on Hames Road. We look forward to seeing you.

Looking back at the van from over the flower display in Berkeley

Check this link if you’re interested in volunteering. https://www.mariquita.com/friends-of-ladybugs-labyrinth/

Glamping With The Ladybugs

Our farm isn’t just a place for the wild creatures to take refuge from the civilized world, or for a civilized soul to find refuge from a wild world. Mariquita Farm is also a working farm and one of our main crops are beans.

“Albert Einstein slept here,” Albert Straus said, as he showed me to my room.

“Albert Einstein came to Marshall?” I was incredulous.

“Talk to my father and he’ll tell you that, sooner or later, everyone comes to Marshall,” Albert said.

The Straus Ranch is perched on the shores of Tomales Bay, near the settlement of Marshall, halfway between the towns of Point Reyes Station and Tomales. A sloping drive lined with ancient, wind twisted, dark cypress trees led down from the old, white, Victorian ranch house down to Highway 1, with the cold, choppy, bay waters slapping at the shore just a few yards past the road. It’s the edge of the continent, the middle of nowhere, a windy rangeland populated mostly by dairy cows, and seagulls. Marshall is isolated, but beautiful, and in 1979 I had the fortune to spend a season living there and working for the Strauss family on their dairy.

Besides our market crops we grow lots of flowers for fun, including over 100 different kinds of roses. This is an old, Italian heirloom rose called “Variegata di Bologna.”

Over time I learned the family’s story in more detail. Bill and Ellen, Albert’s parents, had come to America as Jewish refugees from the Nazi occupied Netherlands. They had a friend in common with Einstein, who had fled Germany when the Nazis came to power. To the racist ignorati, Einstein’s Theory of Relativity was “Jewish Physics,” and they wanted to kill him for thinking creatively. Luckily, Einstein found a refuge at Princeton’s Institute for Advanced Studies. He would continue to work on the puzzles of relativity the rest of his life and when he wanted to be alone with his thoughts he could decamp from academia and spend some quiet time in Marshall with the Straus family and their Holstein cattle.

We have a half mile of trails that link three different redwood fairy rings in Pinto Creek Canyon along the edge of the property.

I was hired because Bill Straus had “retired” and Albert needed help with the chores. Mr. Straus, “retired” though he was, still put in long days of work on the ranch. Besides their home ranch, the Straus Dairy rented a second ranch a few miles down the coast in Marshall called the Pauli Ranch, where they grazed the “open” heifers that they were waiting to breed once they reached maturity. On my day off, when I wasn’t available to go to Marshall and feed the heifers, Mr. Straus would do the work. Bill saw me one day when he returned from the Pauli Ranch.

“You’ll never guess who I saw in Marshall,” he said.

I couldn’t. A large, Victorian era hotel in Marshall had, until recently, been occupied by a drug and alcohol treatment organization called Synanon, but they’d gone cult and tried to kill the lawyer, Paul Morantz, who was checking into their affairs by putting rattlesnakes in his mailbox. Mr. Morantz didn’t die. Now Synanon was being sued, and their hotel in Marshall was up for sale. The real estate agent was showing the property to institutional buyers to see if he could sell the place as a potential spa, hotel, or spiritual retreat center. When the real estate agent saw Bill Straus pull out of the Pauli Ranch, he waved him over. If anyone in Marshall could be counted on to make a newcomer feel welcome, it would be Mr. Straus, who was always gracious and understanding.

“Bill,” he said, “allow me to introduce you to his Holiness, the Dalai Lama. Your Holiness, Mr. Bill Straus.” The two exiles shook hands and greeted each other warmly.

“That’s amazing,” I said.

“Sooner or later everyone comes to Marshall,” Bill replied.

Here I am walking around the edge of the labyrinth with Starr’s granddaughter, with one of the three corn patches on my right.

I owe the Straus family a lot. Not only did they put up with me for a year, but after I’d left the ranch and gone back to college they were very helpful to me. Albert’s mother, Ellen, observed that I had taken a lot of interest and initiative in getting a vegetable garden going while I was living on the dairy.

“Maybe you should go into organic vegetable farming,” she told me. And she gave me the address and phone number of Warren Weber, her neighbor down the coast in Bolinas who owned and operated Star Route Farm. With Ellen’s good references I was able to get a job there and I’d spend five years in Bolinas learning the vegetable trade from “the ground up.”

Our “Glamper’s Yurt” nestled between the Meyer lemons and the Makrut limes.

Now, 43 years later, I’ve got my own farm in Corralitos and it’s as lovely in its own way as the Strauss Dairy in Marshall or Star Route Farm in Bolinas. For fun and as an outdoors art project my partner, Starr, and I have chosen to create an eleven circuit labyrinth that’s 110 feet wide and plant it out in lavender. The labyrinth is embraced by citrus orchards and the beds of herbs, vegetables, and flowers that we tend. In the redwood canyon we’ve created quiet walking trails that link the redwood fairy rings one to another. Our next project is the creation of a wildflower meadow to sustain the birds, the bees and the butterflies.

The yurt is roomy and you can see the stars overhead on a clear night.

Our farm is a twenty acre refuge in a crazy world. Maybe, like Albert Einstein, you’d like a farm to hang out on when your thoughts get heavy. Maybe, like the Dalai Lama, you want a meditative environment for workshops and events. If you’re a “glamper,” we’ve got a big, big tent with a bed, a table, and an outdoor kitchen. If you’re a bird watcher, we’ve got a turtle pond full of ducks, egrets and geese. We’ve even seen a Bald Eagle on occasion although when the eagles show up the other birds clear out. If a stay on our farm looks attractive to you check out the “Amenities” section of our website for more details and photos. https://www.mariquita.com/venue-rental/

The work never stops here, and we welcome volunteers. We can especially use help weeding the labyrinth since we use no herbicides. During the rose season it’s great to have some help “Dead-heading” the roses. Here’s the link to our volunteer signup. https://www.mariquita.com/friends-of-ladybugs-labyrinth/

Thanks, and we hope to see you soon.

Our climate is temperate and mild because we’re only about 12 minutes away from the Monterey Bay. This is Aptos Beach at Rio Del Mar.

© 2023 Essay by Andy Griffin

Tomatoes

My feet are tapping. In my head, I can hear a vigorous horn section celebrating my every thought with a jazzy fanfare; it’s like I’m channeling Louis Prima today. If you don’t think you’ve heard of Louis Prima, he’s the hitmaker from back in the day who gained fame for his songs, “Yes! We have no Bananas” and “Just A Gigolo.” I’m in the fruit and vegetable business, not in the escort services, so it’s produce that’s got me jumpin’ and jivin’ with Louis. “Yes! We have no Tomatoes, Toot Toot!” “But we will soon. Toot Toot!”

Musicologists will tell you that “Yes! We Have No Bananas” was a novelty song in the jazz idiom from the first quarter of the 20th Century. Louis Prima didn’t write the piece, but he had a hit off it in 1923 and, later, other artists, like Benny Goodman and Spike Jones, made popular recordings of the song too. Boiled down to its essence, the song is a lark that finds fun in a Greek produce vendor’s reluctance to say “no” to his customers. “Just try these coconuts, ” Louis sings.” These walnuts and doughnuts, there aren’t nuts like they…But, Yes! We have no bananas, we have no bananas today.”

Rainbow Cherry Tomatoes are not a special breed, but a mix of various breeds. The big, red Cherry tomatoes are actually an heirloom Italian paste tomato called “Piennolo.”

Heirloom “Persimmon” tomatoes

The tomato patch

Agricultural historians who listen to old jazz records hear something deeper at work and speculate. Maybe the Greek produce vendor couldn’t get bananas because of the Fusarium oxysporum plague that destroyed the Costa Rican banana crop in 1919. Also called “Panama Disease,” the fusarium fungus causes a wilting disease that has dramatically affected the banana trade any number of times. But what about the tomatoes? Why are we still singing, “Yes! We have no tomatoes.”

It was a cold spring and, so far, it’s been a cool summer. We planted the tomatoes right on schedule in early April and crossed out fingers that the frost wouldn’t get them. It didn’t. But it never got very warm, either, so the tomatoes didn’t grow very fast. We had weird, late rainfalls, but the rain didn’t hurt the crops. The rain didn’t help either. The late rains meant that we had to weed more often than we’d like, but the precipitation didn’t harm the tomatoes. Still, with day after day of overcast weather, the tomato plants were slow in taking off and flowering. If the tomato plant is thought of as an engine, then the nutrients in the soil are the fuel and the water is the lubricant, but the sun is the foot on the gas pedal. Some people think that you can speed a slow crop up with extra fertilizer, but if the issue is not enough warm sun then all the fertility in the world can’t help.

So, yes, we have no tomatoes, but we will. I figure we’re about three weeks late this year. The cherry tomatoes will come first because they are the smallest fruits and ripen the quickest. The dry-farmed Early Girls are “Early,” too, and will start to color up a week or so after the cherries.The rainbow array of Heirloom tomatoes come a bit after the Early Girls.The Heirlooms vary from variety to variety when it comes to the speed with which they mature. Cherokee Purple is usually the first and the Marvel Striped Tomato is usually the latest with the others, like the Brandywines and the Persimmons and the Aunt Ruby’s German Green falling somewhere in the middle. The San Marzano canning tomatoes and the Piennolo drying tomatoes come last.

Look at this big boy enjoying his Dry Farmed Early Girl tomatoes!

We will have lots of flowers this year too.

We will not be running our Mystery Box program this year, but we will be doing pop-ups around the Bay Area to sell our tomatoes, herbs, citrus, and flowers starting in August and running through the end of tomato season. We will be returning to Dogpatch in San Francisco, thanks to our hosts at Piccino restaurant. In the north of the City we will be back at our regular site in the Richmond District. Across the bay, we will be back in Berkeley on 9th street, and down the Peninsula we will be back at Ross Road in Palo Alto. The Pumpkin House is our hangout in Santa Cruz. Also, keep an eye on the newsletter for updates because we will be doing some open farm days with tomato and flower pickups. The sun is out now, the plants are in full flower, the green fruit is swelling, and it’s looking like we can get started in mid August. Yes, we will have tomatoes! Toot Toot!

Thank you, and we hope to see you soon! Andy & Starr

Check this link if you’re interested in volunteering. https://www.mariquita.com/friends-of-ladybugs-labyrinth/

© 2023 Essay by Andy Griffin

Just Ducky

Pinus Sabiniana along the road to Carrizo Plain. My father did his doctoral thesis on this tree species, which used to be called the “Digger Pine,” because the Native Americans gathered around them to collect the rich, flavorful seeds. Dad cautioned me that it would be best to call the plant by its scientific name, or at least one of its other nicknames, like “Ghost Pine,” “Gray Pine,” or “Bull Pine,” so as to avoid offending people. Waking up to the more painful parts of our history, like the genocide of Native Americans, is NOT the problem. “Woke” is no joke. The politicians who would seek to keep knowledge about slavery or genocide under wraps are not patriotic, just too scared to peek out from behind the flag.

One of the things some Yankees found barbarous about the Indians they met in the “new” lands they occupied, was that, for indigenous residents, cooking up some grub might mean cooking up some grubs. Grubs are beetle larvae. Scientists can tell you that, as a food, grubs are high in antioxidants, essential amino acids, and vitamins, and the Indigenous cooks could give you some recipes, but most contemporary consumers in the US would say that grubs are nauseating, like maggots. Scientists and Indians could tell you that maggots are good food too, but even the word “maggot” is enough to reliably summon forth a host of “food issues” for many folks.

Here’a a cool, metallic, silver Beetle I encountered today in the Apple mint. DId you know that before they were “The Beatles” John, Paul, and George were briefly “The SIlver Beatles?”

The American pioneers saw the locals they were displacing using sharp sticks to scratch in the soil and unearth such grubs, and they called them “diggers,” using the term as a dehumanizing pejorative, like the “n word,” but with a “d.”

Over a hundred years later, in 1966, community-minded anarchists in The San Francisco Mime Troupe began to toy with the idea of leaving the urban psychedelia of Haight-Ashbury behind and going “back to the land.” They called themselves The Diggers.

These modern, countercultural “diggers” took inspiration, in part, from a group of 17th Century agrarian socialists in England who sought to create a subsistence farming movement on Common Lands and who had been called “Diggers” by both friend and foe. The new 60s “Diggers” also looked to California’s First Peoples as role models for a renewed ecological consciousness. The biggest food issue that the Diggers could see was the problematic role of Capitalism in the food system.

The old pejorative term “Digger” had a resonance for these activist hippies. They appropriated the old anti-Native American racist slur to define their own identity and contrast themselves with the corporate war machine. Can you dig it?

The Haight wasn’t the only psychedelic neighborhood. Oaxaca seems to have an aptitude for the surreal & psychedelic. We took a trip there and saw this old airplane at the Huatulco airport. Strap on those seatbelts; it’s going to be a colorful flight!

Grubs have always been too much of a challenge for me to eat, but that’s my social conditioning speaking, not my rational brain. There are many smart people advancing the idea that human consumption of insects, larval or otherwise, could be key to eliminating world hunger.

Even if you don’t want to eat grubs like popcorn, one after another, insects may become part of our food chain. The world’s resources of marine creatures have been devastated, for example, by overfishing— and a lot of fish are ground up to make organic fertilizers.

If insects, like flies and maggots, were raised on a vast scale to be processed into fertilizers, utilizing human food waste as a growing medium, we could reduce our dependence on already depleted fisheries even as we reduce the amount of waste going into our dumps. We could reduce the amount of methane escaping from the dumps and contaminating the atmosphere. Also, protein powders derived from farmed insects could be valuable as food additives for processed foods like breakfast cereals, by increasing the food value of these products even as we disguise the existentially-uncomfortable source of their nutrition.

A Oaxacan moth – or is it a butterfly? – at the Huatulco Airport. Corn ear-worms are the larvae of the Corn moth, and every Oaxacan farmers market will have someone making them into tacos.

A Triqi Indian labor crew from Oaxaca once schooled me in this matter of eating insects.

We were picking some fresh corn for the farmers market, and I asked three of the crew to pluck the nasty-looking corn ear-worms out of the corn ears so that our sensitive customers would only see the silky yellow ears. Corn ear-worms are the larval form of a moth. I was surprised to see the guys carefully collecting the ear-worms into a clean bucket.

“You don’t have to treat them like treasures,” I said.

They laughed at me. For lunch, they boiled some salted water over a camp stove and blanched their catch of plump worms for a few seconds. They removed the pot from the flame, drained off the excess water, and quickly pan-fried the worms to make them crispy. They folded the fried worms into warm corn tortillas, added a splash of tomatillo sauce, some chopped cilantro and onion, and finished off with a squeeze of lemon. “Voila!”— I was presented with a plate of traditional Oaxacan tacos.

“These are always popular during the corn harvest,” they told me.

A rose fed escargot eating out the heart of a rose as it fattens itself for the farm-to-white-tablecloth crowd.

But Native Americans don’t have a monopoly on eating agricultural pests. Example Deux: the French. One environmentally sophisticated response to an infestation of snails is to gather them from the field, cleanse and fatten them on cornmeal, and cook them up as “escargot.” Only an ancient, refined, and ironic culture can think to control pests by drowning them in butter, smothering them in chopped garlic and parsley, and serving them up to be eaten, with their minced and marinated flesh re-cupped into their very own shells and plated on china, right next to a serving of the vegetable that they once molested.

I could eat a length of garden hose if it was cooked with enough butter, parsley, and garlic, but eating agricultural pests as a control measure is not a solution that everyone can swallow. Observant Jews, for example, won’t eat mollusks, because they’re not kosher. Snails are mollusks, but so are their cousins, the slugs. Even the French won’t eat slugs.

It was taken as gospel among the hippie homesteaders I grew up around in the Bay Area, that ducks will eat all the slugs and snails they can find in a garden. I once worked on a farm with a patch of artichokes that was being obliterated by a snail plague. You could walk down one row with a 5-gallon bucket and strip enough fat, round snails to fill it.

I couldn’t stand to see a vast mess of snails destroy our crops. I had a vision of fattening a flock of ducks off of all the slugs and snails, and then selling the ducks to French restaurants for duck l’orange. It was a “kill two birds with one stone” idea, except that I’d be killing a million slugs and snails, plus any number of fattened birds.

I left the farm, drove around the shores of Bolinas Lagoon to Highway One, and north to Point Reyes Station, where I purchased two happy ducks for fifteen dollars: a drake and a hen.

Before she would release the birds into my custody, the duck dealer, a middle-aged woman who spoke of the ducks as her “feather children,” made me promise on all that was holy that I would not eat them.

I promised; so much for my savory, profitable, and elegant “circle of life” pesticide program!

I could’ve raised the ducks, slaughtered them, and sold them to somebody else, monetizing their ducky lives for a quick profit without breaking a promise. But lying seemed like bad karma. Plus, the young duck couple with their cute white plumage and iconic orange bills, their ridiculous quacking and their incessant butt-wiggling, endeared themselves to me. If the drive back home had been much longer, I might’ve ended up with two feather children myself.

Back at the farm I took the two white puddle ducks to the artichoke patch. I sat back to watch my ecologically-correct mollusk control program take off. The ducks stepped out of the confines of the carton they’d traveled in, took one look at the snail-infested artichoke patch, eyed the bright waters of the Bolinas Lagoon shimmering in the distance, and flew to freedom.

The duck lady wasn’t happy to see my return. She feared for the safety of her two backyard ducks once they had to face the cruelty of nature. Would the wild mallards on the lagoon welcome them into their flock? Or would the two cute white ducks be shunned as albino freaks and left to fend for themselves, surrounded by bald eagles, hawks, owls, coyotes, foxes, dogs, bobcats, mountain lions, skunks, raccoons, and snakes?

In the end she agreed to sell me two more birds. I prevailed upon her to teach me how to clip their wings. “We wouldn’t want them to fly off and get eaten by bobcats in the wild, would we?”

When I got back to the ranch I locked the two ducks up in a large, empty chicken coop. The ducks made such a cute couple, I caught myself counting my ducklings before my hen even got laid. We would probably have to hire a duck herder just to guide our flock from field to field!

I gathered up a five-gallon bucket full of snails, and dumped it into the coop so my new feathered helpers wouldn’t get hungry. I was hungry too, after my morning’s work, so I went to my cabin for lunch.

When I returned a half-hour later, I was surprised to see the ducks cowering in the corner of the cage, surrounded by a slobbering mob of snails.

Two ducks, thirty dollars, and a million snails added up to exactly zero. Apparently these ducks, like so many of us, had “food issues.”

The Grateful Dead have evolved into a myriad of forms over the year, including this iteration, Dead & Company. I took this picture of their iconic Dead Head logo in Chula Vista

Our lavender labyrinth and flower gardens are a labor of love and we can always a little help, especially with weeding in the lavender or dead heading in the roses. “Dead-headers” don’t have to be Dead Heads. Check this link if you’re interested in volunteering as a “Garden Gnome.” https://www.mariquita.com/friends-of-ladybugs-labyrinth/

© 2023 Essay by Andy Griffin