Letters From Andy

Ladybug Letters

Cultivating Luck

We’ve turned up three rusty, old horse shoes as we’ve gone about getting the “windmill field” ready to plant next spring, so does that make us lucky? I think so. Consider the facts:

My Great Grandfather Griffin farmed this field during the earliest years of the 20th century and the horse shoes were undoubtedly shed by his draft horses. My uncle told me once that the family had a contract at that time to grow cucumbers for Heinz pickles. They probably got a good crop because the soil is rich. They probably didn’t get a good price though, because my Great Grandfather ended up selling the field to Marius Jorgensen, a Danish immigrant who worked as a bricklayer in town. But, as luck would have it, during the sale my Great Grandfather’s son met Marius’s daughter, Anna, and the two youngsters got married, so the field stayed in our family even after the rest of the original Griffin ranch got sold off to pay debts, and eventually I was able to buy the land from my Uncle.

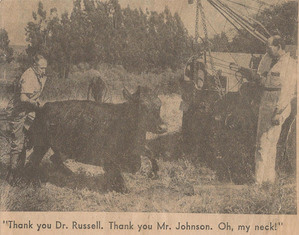

Clipping from the Register Pajaronian (circa 1955) showing Grandma Anna’s cow rescued from the well.

During the years that my Danish Great Grandpa had the land it was leased at one point to a flower grower who produced Calla lilies, and there are some feral lilies that still thrive in the edge of the field where a seep spring keeps the ground wet. There’s another spring under the windmill. My Great Grandpa Marius dug that spring out and he built a brick-lined spring box with a windmill above to lift the water to the surface where it filled a water trough for livestock that grazed the ground after the flower farm moved on. In the mid 1950s my Grandmother’s cow fell down into that well. A tow truck was able to haul the cow out, which was lucky, but Grandma ended up in the local news over that incident when a photographer for the Register-Pajaronian snapped a picture of her with the distraught cow hanging from the tow sling. Sudden fame made Grandma cross, because she’d never sought celebrity.

Graydon harvesting pumpkins 20 plus years ago.

I grew pumpkins and beans in this field in the late 1990’s and these crops did well. When I turned my attention to farming larger sections of leased ground, I put the field back into pasture for my donkeys. With a much smaller business these days, and much higher ag land rents to choke down, it makes sense to farm the field again. So, even as we wrap up all our work for the 2021 season, it’s already time to be planning and prepping ground for the 2022 season. The donkeys have been moved to the next field over and I put up a sturdy fence yesterday to make sure that they stay there. Like my Great Grandpa, I’ll plant some cucumbers, but I’m also planning on raising some beans. And not just any beans! These will be vining, “Jack and the beanstalk” style, “lucky” beans that can send runners climbing 20 feet high if they can find something to scale.

Akahana and Shirohana beans.

Our 2021 experimental bean crop at the land I farm along Freedom Blvd was a success. A successful experiment means that you learn something and, even a trial crop “fails,” the crop is still a success if you learn something. The beans I grew on rented ground were the purple Akahana mame and white Shirohana mame beans – Japanese selections of a runner bean that is native to the Oaxacan highlands. These are the same beans that I grew in this field when my son was a little boy. This year I found a ready market for the small crop of beans that I produced and I calculate that if I don’t spend so much money on rent next year then I can maybe even profit a bit if I grow a larger crop. Between the price of rent, poles, trellis wires, water and a lot of hand labor there are serious costs associated with growing runner beans, which is why you don’t see so many of them in markets. I’m lucky to have my own ground that I can plant into, and my own water to pump.

This past Saturday I was ready to winnow the beans I’d saved for our farm’s harvest box customers. It was warm and the bean pods were dried well but there was no breeze at all. So Starr plugged an extension cord in, strapped on her electric leaf blower, and took a turn as a new age Aeolus, whipping up a stiff wind to carry away the chaff from the stream of beans that fell as I poured them from one barrel into another. We will select some of these beans to plant next spring, and the rest we will put in this 2021 season’s last harvest box.

Another successful experiment this year was our Chayote crop, so I’ll be building a frame for a larger planting that will cross the windmill field. When our experimental chayote crop came in with a larger yield than expected Fidel, our foreman, sold the extra chayotes to the crowd of Oaxacan women who gather at the laundromat his wife frequents. The Oaxacan women were very clear; they were excited to get such fresh produce and they asked us to grow Chilacayotes too. Chilacayotes are sprawling plants, so we will put them below the chayote frame towards the end of the field where they can occupy as much space as they want. The thick canopy of leaves that the chilacayotes produce will act to discourage weeds.

Another successful experiment this year was our Chayote crop, so I’ll be building a frame for a larger planting that will cross the windmill field. When our experimental chayote crop came in with a larger yield than expected Fidel, our foreman, sold the extra chayotes to the crowd of Oaxacan women who gather at the laundromat his wife frequents. The Oaxacan women were very clear; they were excited to get such fresh produce and they asked us to grow Chilacayotes too. Chilacayotes are sprawling plants, so we will put them below the chayote frame towards the end of the field where they can occupy as much space as they want. The thick canopy of leaves that the chilacayotes produce will act to discourage weeds.

Along the soggy margins of the field where crops won’t grow we’re going to plant redwood trees. Starr and I have a program of planting some redwood trees every year as a gesture to the future. We’ve planted 15 of them so far. We usually buy a live redwood for a Christmas tree and then plant it out when the holidays are over, but every time we see a reasonably priced tree in a nursery we buy it. Long before my great grandfathers were here this land was a dense redwood forest, and it feels good to be replanting some trees. Since we’re planting the trees on the north side of the field they will never shade the field, but they will offer the field some wind protection. Besides, the earth needs help with CO2 and redwoods are great carbon sinks. We are lucky people to be living here and farming this ground, so planting redwood trees every year seems like an appropriate Christmas gift back to this land that has given us so much.

And speaking of gifts, if you are looking for a stocking stuffer…

And speaking of gifts, if you are looking for a stocking stuffer…

Persimmons

Mr Raccoon leaves big dirty foot prints on the stairway.

It was the thump overhead that woke us up, followed by violent sounds of thrashing and scraping. From my warm, cozy nest in the bed below it seemed as though an inebriated Santa Claus had just crashed his sleigh into our chimney and now the reindeer were tangled in their harnesses and scrambling for footing on the steep roof. I was befuddled and drowsy but it’s only early November so in my rational mind I knew that the scandal on our roof couldn’t possibly be a consequence of Christmas. “The persimmons must be ripe again,” I decided; “They’re sure an attractive nuisance.” Dissing fruit isn’t a popular stance for a farmer to take, so let me clarify myself by first spelling out what makes persimmons so attractive before I dig into what makes them such a pain.

Hachiya Persimmon Tree

Persimmon trees are beautiful, and the rich, deep orange and red hues that their leaves take on in the late fall are as close as we Californians can get to “fall colors.” I remember working on a farm in the Sacramento Valley when I was 20 years old, and one grey, cloudy autumn day we were sent to pick persimmons. There had been a storm the night before and the wind and rain had knocked all leaves to the ground so the fiery, heart-shaped fruit hung from the wet, black branches like jewels- a sight so stunning that I’ve never forgotten it. These were the Hachiya persimmons, the kind that ripen to a slippery, pudding-like goo that is almost obscenely sweet. Another popular persimmon variety is the squat shaped, dusky-orange Fuyu, which has more of an apple-like texture when ripe.

Fuyu Persimmon Tree

When I finally studied up on persimmons I was surprised to learn that the plant is in the same family as the Ebony tree. It takes a persimmon tree a hundred years before it develops the black, tightly grained wood so characteristic of ebony, so it is not a major commercial hardwood but its fruits are appreciated across Southwestern Europe, Asia, and America. Two Japanese persimmon varieties, the Hachiya and the Fuyu, are the most commonly cultivated types available to American shoppers, but interestingly our name for these Asian plants comes from the native American Powhatan word pasiminan, or pessamin. A number of different persimmon species are native to North America, ranging from Connecticut down into Northern Mexico. There are plenty of people who gather and eat the native persimmon types but the American persimmons don’t yet get the shelf space in supermarkets that the Hachiya or Fuyu varieties command.

Wild Persimmon are much smaller than the Hachiya and Fuyu varieties. You can eat them off the branch once they’ve turned dark, wrinkled and raisin-like.

Plant scientists have discovered that the germination rate for persimmon seeds goes up dramatically if the whole fruit first passes through the gut of a zoo elephant leading some researchers to speculate that the American species evolved in companionship with the ancient megafauna like the Wooly Mammoth. Now that the Wooly Mammoths can only be found frozen in the tundra or mired in the La Brea tar pits it appears that their taste for persimmons has been taken up by lesser fauna, like the raccoon, which brings me to the nuisance part of this story.

My grandparents planted two persimmons next to our house back in the late fifties, one Hachiya and one Fuyu. These trees frame our home and shade it during the warm months of summer. We live in the country so we share our space with raccoons whether we want to or not. Some mornings we see their muddy footprints on our porch marking where they’d shuffled around, peering through the French doors at us while we were sleeping the night before. But during the fall when the persimmons ripen the coons become overtly obnoxious. Each of our trees have hundreds of fruits hanging from the branches. You’d figure that with all that fruit we’d have enough persimmons for all of the critters and people to enjoy, but that’s not how things work out.

Mr. Raccoon was cute when he was a baby, but now he’s grown up into a big, stinky, brawling thug of a beast with needle sharp teeth. He never went to kindergarten so he never learned to share. He wants to hog ALL of the persimmons just for himself. His numerous cousins and uncles, ex-wives, lovers and children are similarly charm-free and they share his greedy appetite for sugary sweet fruit. As the persimmons begin to color up among the green leaves Mr Raccoon clambers up the tree trunks and strolls across our roof, checking first on the progress of his Hachiya crop and then giving his Fuyu trees a sniff. When he meets another raccoon, similarly bent on eating ALL of the fruit, the two coons snarl out a challenge and the fight is on to see who really owns the crop.

Mr. Raccoon was cute when he was a baby, but now he’s grown up into a big, stinky, brawling thug of a beast with needle sharp teeth. He never went to kindergarten so he never learned to share. He wants to hog ALL of the persimmons just for himself. His numerous cousins and uncles, ex-wives, lovers and children are similarly charm-free and they share his greedy appetite for sugary sweet fruit. As the persimmons begin to color up among the green leaves Mr Raccoon clambers up the tree trunks and strolls across our roof, checking first on the progress of his Hachiya crop and then giving his Fuyu trees a sniff. When he meets another raccoon, similarly bent on eating ALL of the fruit, the two coons snarl out a challenge and the fight is on to see who really owns the crop.

So we get our ladders out and we pick the crop. Otherwise there’s no sleep for us. Luckily, picking persimmons is a nice chore and reaching among the brilliant, orange and red leaves for the beautiful, glossy fruits is not anywhere near as onerous as picking lemons from amidst their thorny branches. And once the harvest is in the fun begins. Yes, if they’re ripe you can eat them out of hand. I especially enjoy eating the fresh Fuyu persimmons as I find the Hachiya almost too sweet. But I never have turned down an opportunity to eat persimmon bread or persimmon cookies. A lot of people enjoy making Hoshigaki, the air-dried persimmons that are such a favorite in Japan. Our friend, Jonathan, has made a tradition out of making hoshigaki. Below are some pictures which illustrate that process. Persimmons have more of a “moment” than a “season” so I hope you enjoy them while they last. And don’t worry about the Raccoon family — they’ve had their turn; now it’s yours.

Happy Thanksgiving from all of us at Mariquita Farm!

Rain!

Hi All: We got a soaking rain last week with our six inch deep rain gauge overflowing before it could measure the total precipitation. With the ground now nice and moist the soil will begin to cool as the water evaporates. Typically, we get our first frost on the first nice, clear night after a big fall rain, when the nights are long and chilly. It’s overcast now, so it won’t frost immediately, but we need to get everything that’s vulnerable in the barn before it does hit.

I’ll be picking as many chayote as we have. I’ll put them in the share boxes until we run out, then switch over to potatoes. The soil blankets the potatoes, which have not yet been dug, so they’re protected.

This is the last week of picking tomatoes too, I suspect. And peppers, though we will have some shishito a while longer as they are planted in the greenhouse. We’re busy in the greenhouse, but my next phone call is to the tractor repair shop because the seal on the Power Take Off /transmission seal just blew. That’ll have to get fixed before we can work more ground up under the roof. Luckily, we have a bunch of beds already prepped, so we shouldn’t be delayed too long.

This is the last week of picking tomatoes too, I suspect. And peppers, though we will have some shishito a while longer as they are planted in the greenhouse. We’re busy in the greenhouse, but my next phone call is to the tractor repair shop because the seal on the Power Take Off /transmission seal just blew. That’ll have to get fixed before we can work more ground up under the roof. Luckily, we have a bunch of beds already prepped, so we shouldn’t be delayed too long.

Thx A

Fire On The Mountain

It was hot last Friday afternoon as I returned home from my produce deliveries to the Bay Area. As I turned the truck from Freedom Blvd onto Corralitos Road I passed the big wooden Smokey Bear sign and noted that the fire danger sign that he holds was red and said “high.” I was not surprised. Usually the sign reads “high” or even “extreme” from early June all the way until the first rains in the Fall bring some welcome moisture.

Have you ever met a celebrity? The biggest “name” I’ve ever encountered was definitely Smokey Bear- the real Smokey Bear- back in the summer of 1966 at his residence in the Washington DC zoo. My father had been a forest fire fighter to put himself through college, and in the early ’60s he was working as a plant ecologist for US Forest Service, stationed for a while at the USDA headquarters in DC. He took my sister and I to visit the famous bear. I think about my father every time I pass one of those wooden Smokey Bear signs and I remember him joking around and modeling his official “Smokey Bear” hat that was part of his regulation uniform.

My thoughts snapped into the present when I parked my truck in the yard. A friend dropped by to visit at that moment and he pointed out a wisp of smoke rising out of the forest in the Santa Cruz Mountains just to the north of the farm. Within minutes the wisp had turned into a plume that was rising into the sky. Yikes! And pretty quick there was a spotter plane circling the smoke cloud, and then helicopters and tanker planes laying down retardant. It turns out that the fire was a “control burn” on the Estrada Ranch that turned into an “out of control” burn. I don’t know who permitted the burn, and I can’t imagine what they were thinking.

My thoughts snapped into the present when I parked my truck in the yard. A friend dropped by to visit at that moment and he pointed out a wisp of smoke rising out of the forest in the Santa Cruz Mountains just to the north of the farm. Within minutes the wisp had turned into a plume that was rising into the sky. Yikes! And pretty quick there was a spotter plane circling the smoke cloud, and then helicopters and tanker planes laying down retardant. It turns out that the fire was a “control burn” on the Estrada Ranch that turned into an “out of control” burn. I don’t know who permitted the burn, and I can’t imagine what they were thinking.

Don’t get me wrong- I completely understand the “eco-logic” of control burns. If I could, I’d set fire to the canyon on our farm to reduce fuel, reduce poison oak and eliminate eucalyptus. But I wouldn’t have done it on Friday when it was hot and dry, with a breeze, and when Smokey was saying that fire danger was high. What was the hurry? Luckily, the firefighters were able to control the blaze. Today the typical Sunday calm on the farm was ruffled by the sound of big choppers booming overhead as they dipped water out of neighboring Pinto Lake to haul up and dump on the remaining hot spots. When the water would hit the coals a big puff of steam and ash and smoke would go up that we could see from our kitchen window. And now, ironically, the forecast is for 80% chance of rain starting in about a half hour. We’ll soon see if the meteorologists have made an accurate forecast.

In Mexican Spanish there’s a joke where “meteorologos” are called “mentirologos.” “Mentir” is the verb for “lying” , so they’re the scientific liars, LOL. But whether this evening’s 80% forecast is accurate or not, October is the season when nothing can be taken for granted weather-wise. It could rain, or be hot and dry, or we could get slapped with a sudden frost. Anything goes in the fall and the nights seem suddenly longer. There’s a reason that Fall is the spooky, uncanny season where the rich sweetness of the earth’s bounty is mixed with images and portents of mortality. Winter is approaching.

This week’s harvest box showcases the ambiguity of the seasons. Bright red pomegranates speak to the warm days of summer past that fueled the growth of fruit and filled them with sugar. We still have tomatoes and peppers- it hasn’t rained or frosted yet! But the brassicas, like kale and napa cabbage, speak to the cold tolerant green crops that thrive in the cooler months. And we’ve got the first of the colored daikon that will be bright on the plate even when the sky overhead is dull gray.

I’m pleased that we gathered the Oaxacan Pinto corn in from the field before the rain hits and spoils it. We will offer it on the side over the next couple of weeks. It’s beautiful and ornamental, but you can make purple cornmeal out of it. I’m looking forward to some purple polenta in the weeks to come. If it doesn’t rain then we’ll have one more blast of San Marzano tomatoes before the end of the season. Watch for updates. If you haven’t gotten any tomatoes for winter sauce or you don’t have any time to can, fret not!- our friends at Happy Girl Kitchen put a 1000 pounds of our harvest into jars so we’ll have that available.

Postscript:

It did rain last night- for about seven minutes- and now the dust has settled.The sky is clean, the pumpkins in the little patch by the chicken coop are rinsed clean of dust, and there’s a crispness in the air. But I’ll bet Smokey will still say fire danger is high. We need more than a spit and a drip from Mother Nature to reduce the fire hazard.

Consumer Alert

Use a vegetable peeler to remove the spines. Even the spineless ones are best peeled so as to remove the tough hide. Chayotes are in the squash family, but they behave somewhat differently than their zucchini cousins. Once harvested, chayotes can remain happy and healthy sitting in a bowl, not even refrigerated, and the tough hide is part of their strategy. In fact, if you don’t cook your chayote up, eventually a stem will emerge from the bottom of the fruit. You could just pop it into a pot of soil and it will grow into a sprawling, vining, jungly glory in your garden. I provide a frame to control mine.

Use a vegetable peeler to remove the spines. Even the spineless ones are best peeled so as to remove the tough hide. Chayotes are in the squash family, but they behave somewhat differently than their zucchini cousins. Once harvested, chayotes can remain happy and healthy sitting in a bowl, not even refrigerated, and the tough hide is part of their strategy. In fact, if you don’t cook your chayote up, eventually a stem will emerge from the bottom of the fruit. You could just pop it into a pot of soil and it will grow into a sprawling, vining, jungly glory in your garden. I provide a frame to control mine. discover the big, fat, immature seed at the heart of the chayote, looking not unlike an avocado pit. Scoop out and discard the seed. Now you can slice the flesh into cubes. Raw, the flavor is not unlike an unripe melon- crispy and almost sweet, like a firm cucumber. You can enjoy the chayote raw in salads, but it is typically cooked. I cooked up mine as though it were zucchini, with some herbal salt, a twist of black pepper, and a squeeze of lime. It came out very nicely as a side dish. There are a lot of Mexican dishes that employ chayote, but I also ordered a chayote dish in a local Chinese restaurant recently just to try it. Because the flavor is mild it can marry with a wide range of flavors.

discover the big, fat, immature seed at the heart of the chayote, looking not unlike an avocado pit. Scoop out and discard the seed. Now you can slice the flesh into cubes. Raw, the flavor is not unlike an unripe melon- crispy and almost sweet, like a firm cucumber. You can enjoy the chayote raw in salads, but it is typically cooked. I cooked up mine as though it were zucchini, with some herbal salt, a twist of black pepper, and a squeeze of lime. It came out very nicely as a side dish. There are a lot of Mexican dishes that employ chayote, but I also ordered a chayote dish in a local Chinese restaurant recently just to try it. Because the flavor is mild it can marry with a wide range of flavors. Chayote dishes are traditional in Mexico around the season of the Day of The Dead. The plants will yield a harvest up until the frost comes and kills the green leaves. But even when the vines die back the chayote persists underground. The plant makes a starchy tuber under the ground, much like a potato. The chayote tubers are eaten too, and I look forward to trying one out. Mostly, I’m going to leave my plants’ tubers underground so that the plants have a head start on sprouting next season. Since our planting seems to be a success I’m planning on planting a bunch more next spring. As more chayotes set on the vines this season I’ll select about 60 or so of the fattest ones and save as seedstock for next year. I read that in Mexico it is traditional to plant chayote on the 5th of February. I won’t do that. We’re so much farther north so a frost free planting date for planting will come later. I’ll plant my next crop on April Fool’s Day as the next season in farming gets rolling.

Chayote dishes are traditional in Mexico around the season of the Day of The Dead. The plants will yield a harvest up until the frost comes and kills the green leaves. But even when the vines die back the chayote persists underground. The plant makes a starchy tuber under the ground, much like a potato. The chayote tubers are eaten too, and I look forward to trying one out. Mostly, I’m going to leave my plants’ tubers underground so that the plants have a head start on sprouting next season. Since our planting seems to be a success I’m planning on planting a bunch more next spring. As more chayotes set on the vines this season I’ll select about 60 or so of the fattest ones and save as seedstock for next year. I read that in Mexico it is traditional to plant chayote on the 5th of February. I won’t do that. We’re so much farther north so a frost free planting date for planting will come later. I’ll plant my next crop on April Fool’s Day as the next season in farming gets rolling.The New Abnormal

A creeping mist hanging low to the ground kept me from seeing the great V of Canada geese flying overhead last evening but I could hear them honking to one another up and down the line and it reminded me of nature’s timeless patterns and the cyclical drama of the seasons. Fall is upon us. Of course, these Canada geese were probably only migrating from the Spring Hills Golf Course on the north side of the valley off of Casserly Road to the Pajaro Valley Golf Course on Salinas Road on the south side of Watsonville. “Who’s migrating?” they were probably saying. “We like it here.” But the one constant condition in nature is the inevitability of change. Nothing seems “normal” any more.

our longtime customers who buy thousands of pounds of dry-farmed Early Girls tomatoes, like PizzaHacker in San Francisco or Happy Girl Kitchen on the Monterey Peninsula had to postpone or cancel some orders because they couldn’t source the jars that they needed for the sauce that they wanted to make. We worked our way through those issues, but now we’re confronting a cardboard crisis. Repeatedly, over the last month or so, Sambrailo, our local packaging supplier has run out of the boxes we need for cherry tomatoes or single layer tomatoes. Imagine a box company with several blocks of empty warehouses and fleets of idle forklifts while meanwhile all the farmers are screaming for cartons. But what can they do? The supply chain is kinked. Everybody is talking. Some folks say it was the ship that ran aground in Suez and blocked the canal that set the problem in motion. Other people say it’s because the paper industry is stymied by lack of workers. Who knows?

our longtime customers who buy thousands of pounds of dry-farmed Early Girls tomatoes, like PizzaHacker in San Francisco or Happy Girl Kitchen on the Monterey Peninsula had to postpone or cancel some orders because they couldn’t source the jars that they needed for the sauce that they wanted to make. We worked our way through those issues, but now we’re confronting a cardboard crisis. Repeatedly, over the last month or so, Sambrailo, our local packaging supplier has run out of the boxes we need for cherry tomatoes or single layer tomatoes. Imagine a box company with several blocks of empty warehouses and fleets of idle forklifts while meanwhile all the farmers are screaming for cartons. But what can they do? The supply chain is kinked. Everybody is talking. Some folks say it was the ship that ran aground in Suez and blocked the canal that set the problem in motion. Other people say it’s because the paper industry is stymied by lack of workers. Who knows?

Several restaurants, including Chez Panisse in Berkeley, and Zuni Cafe, Perbacco, and Flour and Water in San Francisco, make a practice of saving nice boxes for us. And both PizzaHacker and Happy Girl Kitchen have been good about returning the tomato cartons, so I think we’re good for getting our tomatoes boxed up, at least until the next cargo of cardboard arrives at the box company. So how much longer will we have tomatoes? Hopefully, all month, but once we’re into Fall the harvest depends on the weather…..and on the vagaries of the mysterious supply chain. How are you doing on jars? If you’ve got the glass and you’ve got the time and if you’ll have the appetite for lovely red sauces this coming winter NOW is the time to get your tomatoes. And a big thanks to all of you who have gotten tomatoes from us this season, and a big thanks to all of you who have made the effort to return us the clean boxes that they came in.

Fun Facts for the Vegetable Literate

“FAQs” are “frequently asked questions,” and the reason they are frequently asked is because EVERYBODY wants to know the answers. Amaze your friends with your produce fluency by arming yourself with these fun facts!

Lovage is a member of the Umbelliferae- the carrot family- along with parsley, celery, cilantro, chervil, dill, fennel, anis, and cumin. Like its relatives, Lovage has a strong scent. And lovage is often used as a garnish the way so many of the other Umbelliferae are. I joke that a single bunch of lovage has as much flavor as a whole case of celery, And the flavor of lovage certainly is reminiscent of celery, but it’s a lot stronger; little goes a long way, but it does go well with tomatoes. If you read the small print on a can of V8 juice you’ll see that lovage is an ingredient. Lovage is also a good ingredient for tomato sauces and soups. Lovage even has a role in the execution of a perfect Bloody Mary. That piece of celery often found cluttering up a Bloody Mary? – the most original of all Bloody Mary recipes called for the drink to be sipped through a lovage straw. Lovage stems are hollow, and to sip the drink through a fresh cut stem imparts just enough of the herb’s warming flavor to compliment the tomato cocktail without overwhelming it, whereas celery is just a stick of irrelevant roughage. Because we’re so rich with ripe tomatoes right now – and tomato juice and crushed, jarred tomatoes, it seems like a good time to pick some lovage.

Lovage is a member of the Umbelliferae- the carrot family- along with parsley, celery, cilantro, chervil, dill, fennel, anis, and cumin. Like its relatives, Lovage has a strong scent. And lovage is often used as a garnish the way so many of the other Umbelliferae are. I joke that a single bunch of lovage has as much flavor as a whole case of celery, And the flavor of lovage certainly is reminiscent of celery, but it’s a lot stronger; little goes a long way, but it does go well with tomatoes. If you read the small print on a can of V8 juice you’ll see that lovage is an ingredient. Lovage is also a good ingredient for tomato sauces and soups. Lovage even has a role in the execution of a perfect Bloody Mary. That piece of celery often found cluttering up a Bloody Mary? – the most original of all Bloody Mary recipes called for the drink to be sipped through a lovage straw. Lovage stems are hollow, and to sip the drink through a fresh cut stem imparts just enough of the herb’s warming flavor to compliment the tomato cocktail without overwhelming it, whereas celery is just a stick of irrelevant roughage. Because we’re so rich with ripe tomatoes right now – and tomato juice and crushed, jarred tomatoes, it seems like a good time to pick some lovage. a potato with DNA from a banana?”

a potato with DNA from a banana?”Glimpses of Late Summer

Late summer is an especially busy time on the farm, with harvesting summer crops, and planning and planting for the winter, going on at the same time. Here are a few glimpses of the changing harvests and colors on the farm.

Red Oaxacan Beans

Jimmy Nordello Peppers, Sweet not Hot!

First Ripening Chayotes hanging down from Roof of Frame

Scarlett Runner Beans

Yellow Tusta Peppers—

–© 2021 Photos by Andy Griffin and Starr Linden.

Fall Comes Dancing In!

Our yard is full of “Naked Ladies.” Or you may know them as “Pink Ladies.” Their name in Botanical Latin is Amaryllis belladonna- “belladonna” meaning “beautiful woman” in Latin. These flowers shoot up like flamingo-colored signal flares from bulbs buried in the hard, dry dirt of late summer and announce the onset of fall. I welcome the sight and scent of these voluptuous creatures and they remind me of my childhood.

My father was a botanist who specialized in native California ecology. We lived in an old ranch house in upper Carmel Valley that had rows of these flowers planted outside. Dad told me that the Naked Ladies were originally from South Africa and that they’d originally been imported into the US in the late 19th century and were much appreciated by gardeners at the time. The overwhelming, sweet scent and almost lurid colors were in sync with the overblown Victorian mentality of the era. Since the Amaryllis bulbs are so hardy the plants can persist for years with no care. My dad taught me to look for seemingly stray patches of these flowers in the woods. “When you see these flowers out in the middle of nowhere,” he used to say, “you know there was once a homestead with a gardener.” We’d look around in the grass and sometimes find the bricks of a broken chimney or the outlines of an old foundation.

Our house is newer but my family has been on this property for over a 100 years. The Amaryllis here were planted by my great Grandfather. But as much as these plants are a signpost to the past, they also act as a prompt to remind me of how much work I’ve got to do now. The Amaryllis always bloom here in the first week of September. We’ve got the heaviest harvests of the season to gather, the dry weather means we have plenty of irrigation to do—- and we’ve got the fall plantings to get into the ground. The crops we plant now are the harvests that we’ll make from November thru March. So we’re really busy now and crops are getting planted almost every day of the week. Romanesco cauliflower is in the ground for later in the fall, as is broccoli. Beets and radish are going in this week as soon as the oldest plantings of basil are turned under.

The lovely photo of Naked Ladies in our yard was taken by Starr’s niece, Jenn, who is visiting from the midwest and helping Starr compose and package the gift boxes of preserves and dried herbs that we’ll be offering in mid October as we head into the holiday season.

—© 2021 Essay by Andy Griffin. Photo of Naked Ladies by Jenn and photo of Gift Bag by Starr Linden.

Gobble, Gobble!

The only turkey bird native to California, Meleagris californica, went extinct 10,000 years ago. The wild turkeys that presently…

choose your own verb to insert into this sentence from the following list:

a. plague

b. ornament

c. desecrate

d. populate

e. despoil

f. violate

g. enrich

….California, are not from here at all. Heck, they are not even from Turkey! Turkeys were domesticated from the native wild flocks thousands of years ago by the indigenous peoples of what is today Mexico. Following the conquest of Mexico by the Spanish the domestic turkey made its way to Asia, then down the Silk Road to Europe. These birds probably earned theirEnglish misnomer because they were first imported to the British Isles from ports in the Eastern Mediterranean controlled by the Ottoman Turks. And while the continuous and wide ranging domestication of the turkey led to the development of various farmyard breeds, the wild turkeys that are their proper ancestors never stopped running riot in the forests—- except in California, where over-hunting of the native birds by the native people is likely what made extinct a species we now only know through the fossil record.

Mother Nature has a refined sense of irony. When I decided to plant a milpa this spring I was looking forward to trying out a planting style that was developed in ancient Mexico. In a milpa, a holy trinity of corn, squash, and beans are cultivated together in harmony. The corn grows upright and its thick stocks serve as a ladder for the beans to climb up and find support in. Meanwhile, the squash plants spread out across the ground and choke out any weeds. Even the weeds common in the milpa that do poke through the canopy of squash, like the wild tomatillos, lambsquarters or purslane, are edible and are appreciated for the variety they add to the diet.

Mother Nature has a refined sense of irony. When I decided to plant a milpa this spring I was looking forward to trying out a planting style that was developed in ancient Mexico. In a milpa, a holy trinity of corn, squash, and beans are cultivated together in harmony. The corn grows upright and its thick stocks serve as a ladder for the beans to climb up and find support in. Meanwhile, the squash plants spread out across the ground and choke out any weeds. Even the weeds common in the milpa that do poke through the canopy of squash, like the wild tomatillos, lambsquarters or purslane, are edible and are appreciated for the variety they add to the diet.

In my milpa I chose to plant a Oaxacan corn, a Japanese runner bean and a French squash. All of these crops had, of course, been essentially developed in Mesoamerica before the “Columbian Exchange” but had then found a new

refinement after being cultivated overseas in different countries. I figured that my multi-cultural milpa would be a fun expression of California’s culinary and human diversity. And I haven’t been disappointed. The French Doran squash have scrambled across the ground and cloaked the soil, choking out weeds. The Japanese Akahana mame beans have twined their way up the stalks of Oaxacan Pinto corn, which reach 10 feet high into the sky. I even planted some sunflowers to brighten the corn patch. Sunflowers are yet another invention of pre-Columbian American farmers. But I wasn’t counting on the turkeys.

In Mexico the word for turkey is “guajolote” and there is no food more essentially Mexican than Mole Poblano, or guajolote served in a mole sauce. And mole sauces typically are made rich and velvety with squash seeds that have been pounded into a paste. The people that invented the milpa, that developed the corn, squash, and beans from wild plants into major crops—these people really knew how to live at home in their environment. Not only did they create a number of the world’s most important food crops, they also knew how to eat the pests that plagued those crops. The corn fungus that disfigured the young ears of corn was considered a delicacy- huitlacoche- and when it presented itself in a crop it was welcomed, not treated with fungicide. The grasshoppers that would eat the young corn were gathered to be cooked up to be served alongside the beans and squash. In an elegant twist of fate the corn earworms that eat young corn and leave a disfiguring pathway through the neat rows of colored kernels were themselves cooked in hot oil and served to hungry diners in corn tortillas. And the wild turkeys that dared to invade the milpa were tamed and domesticated. The ancient farmers that created the milpa system of farming were thrifty and creative. Then there’s me….

The packs of wild turkeys that roam my yard haven’t ruined my milpa but they have made success more of a challenge to achieve. These big, fat birds have pecked some of the squash, devoured the sunflowers, and torn up a lot of the beans by thrashing around in the corn patch taking dust baths. I could solve the problem by shooting the turkeys and serving them in a corn tortilla with a tomatillo de milpa salsa. But I won’t. As much as the turkeys annoy me by stealing cat food from my kitty’s bowls, by crapping all over my yard, and by messing up my garden, I do find them entertaining and puzzling. How can wild turkeys be so stupid and still survive? Everyday they come to the fence as they cross the property and walk back and forth in confusion, forgetting that they know how to fly and in fact have flown over the same fence many times before, even earlier that same morning.

So the turkeys walk back and forth along our fence line dressed in stupid splendor, their plumage flashing their psychedelic, iridescent camouflage that so curiously is flashy yet effective at blending them into the grass. Once the turkeys finally do hop across the fence with a simple flap of the wings they line up at the top of our little slope just south of our house. They like to run down the hill that has become their personal runway to help them with their takeoff, and they make a great, noisy beating of their wings before they catch flight. Overhead the turkeys look like pterodactyls as they fly across the sky, heading to the tops of the tall Torrey pine tree at the foot of the hill. Each turkey selects its own tree limb to land on. After some squawking and gobbling and fluffing of feathers they settle down to sleep. The ground below their roosting tree is littered with turkey crap- and with coyote turds because our sharp-nosed canine companions are always hoping for a turkey dinner.

—© 2021 Essay by Andy Griffin. Photos by Starr Linden