Letters From Andy

Ladybug Letters

Good Clean Dirt

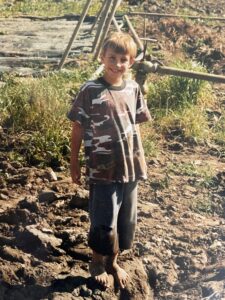

My daughter, Magdalena, as a child in the greenhouse. She’s 26 now.

My theory on child raising was pretty simple- just throw them in the tub at the end of the day and call it good. My kids grew up on the farm, so they were surrounded by dirt. When they were little their mother, my late wife, Julia, was dealing with a first bout with breast cancer, so I had them with me a lot in the field when she was off at the hospital getting treatments or at home recuperating. I’d often be working with the crew for most of the day so the children would be more or less unsupervised, but we did have some rules: Stay out of the poison oak. Don’t drink from puddles. Don’t play with harvest knives or propane weed burners. No turning on the tractor. Don’t pick up anything dead. No throwing rocks, sticks, dirt clods, tomatoes or zucchinis at each other. Always walk down the rows in the wheel track, not on the raised bed where the crop plants are. And Don’t leave your clothes in the field. I know it seems like a pretty strict regimen, but they survived, and there weren’t too many problems. Until we had a tomato U-Pick on the farm and my son ended up mingling with the visiting children. Then I ended up facing down a posse of really unglued mothers. More on that in a minute….

Samson, the apricot blond farm cat, supervising the lavender harvest and remaining chill.

People go to U-Picks for a lot of different reasons. Some people see a farm U-Pick as an opportunity for bonding with each other. When I worked at Star Route Farm in Bolinas in the early ’80s we had a pumpkin patch in what we called the “Lagoon Field,” alongside the Olema-Bolinas Road and we did a U-Pick. Two separate and unrelated fathers showed up at the same time and parked by the side of the road. Somehow, in that very large field with thousands of available pumpkins in every shape and size, their two boys ended up needing- REALLY NEEDING!- the exact same pumpkin. Neither child could be convinced to select another, different, but equally charming pumpkin to take home and carve. Long story short, as the autumn sun got low in the sky giving Mt Tamalpais a golden glow, and as waterfowl circled overhead and came in to land in the placid waters of the Bolinas Lagoon, two fathers could be seen beating the stuffing out of each other by the side of the highway. Over a pumpkin. The cute hippie girl with a background in retail who’d been hired to oversee the U-Pick was horrified. Maybe we should have hired a bouncer. Luckily, fights between customers were rare. U-Pick is actually a very nice way to sell pumpkins, since there’s always a kid who wants the biggest pumpkin, another kid who wants the smallest one, and somebody who feels sorry for the Charlie Brown pumpkin that the other kids overlooked.

We did a potato U-Pick on our farm once. Some people come to a U-Pick so that they can “get their hands in the soil,” “get close to the earth” or find some balance from their typical day jobs in the cubicle mines of Silicon Valley. Boy, did those people get their money’s worth. When you encounter a round, close to clean potato in the store display there is little evidence of the “earthy” environment the potato developed in. But when you put your shovel blade in the soil and start digging you turn up all kinds of stuff besides potatoes. Yes, there are plenty of colorful potatoes, so a potato “U-Dig” can be a bit like hunting for Easter Eggs. But there are also the rotted remains of the mother, or seed potato that was planted in the ground by the farmer for the new plant to sprout from. And there are sometimes big, fat, nasty looking potato bugs chewing on the potatoes that are developing. And there are ants, and centipedes, the occasional scorpion, caches of pearly snail eggs, weird worms, unidentified pupae and larval forms of scary insects. And it is dusty, heavy work. But our potato U-Dig was very successful. I’d taken the precaution of harvesting hundreds of pounds of potatoes before the U-Dig, and we’d washed, sorted, and weighed them out. It was a hot day, and after a half hour of digging all but the most adventurous diggers decided that they’d be happy to buy pre-dug potatoes. I heard the phrase, “I’ll never look at a potato the same way again,” again and again.

Some people go to a U-Pick to pick. We did a number of tomato U-Picks over the years and that’s where I ran afoul of the mothers. Even at age 8 my son, Graydon. had “leadership qualities.” As the visitors picked their way through the tomato patch some of the younger kids got bored and ended up doing a “farm tour” with Graydon, who was very familiar with the layout of the fields. But when nobody was paying attention he took his new friends to what he billed as the “Fun Puddle.” It was a hot summer day but along the edge of the field in a remote corner of the farm there was a large, shallow puddle that had formed where an irrigation pipe had leaked. At first the kids had fun stomping around in the mud with Graydon, but soon he showed them how much more fun it was to actually roll in the puddle. While their parents and older siblings were dutifully harvesting tomatoes, Graydon and his companions joyfully slopped around in the mud as though it were Woodstock ’69 and they were all tripping on acid. The $#iT hit the fan when the moms called it a day and loaded up their harvest and, for the first time in a couple of hours, got a load of what their “leaders of tomorrow” had been up to. “How could you let this happen?” they asked incredulously. But I’d been helping them learn how to pick tomatoes. My attention had strayed. It didn’t help much when I said, “It’s just good, clean dirt. It washes off.” I still feel a debt of gratitude to some Russian mothers from Mountain View. They’d been the most businesslike about picking tomatoes and when it came to their kids they dealt with the situation in a business-like fashion too. They weren’t thrilled with the mud, but they weren’t devastated either. I turned on the ag pump, got the irrigation sprinklers going, and they marched their kids into the spray to clean them up. Even some of the more delicate moms saw the wisdom in this maneuver, and soon everybody was on their way home to the cities and suburbs, tired but alive.

Graydon, the instigator, in the Hollister tomato field.

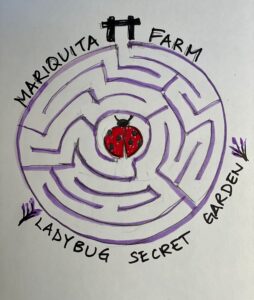

This Saturday, June 10th through June 23rd our farm will be open to make reservations for a series of dates to participate in a lavender U-Pick. I predict a successful experience for anyone who chooses to come and visit us. The lavender is planted in raised beds that make up a huge labyrinth. It’s a serene setting. The scent of lavender is calming and healing, and there’a a lot of it, so I don’t expect to see anybody coming to blows the way that can occur when two fathers choose to stand up for their sons’ “rights” to a particular pumpkin. There are creepy crawlies in the soil, the way there always is, but the nature that any visitors experience is likely limited to birds, butterflies, and bees. For their part, the bees will be minding their own “bees-nis,” working hard to collect pollen and nectar for their hive at the top of the hill. The high raised beds of the lavender patch make for relatively easy picking, but we will have some lavender bunches available for people who want extras and there will be some other herbs, citrus from our orchards, edible items and treasures available in the farm store.

This is a great time to see the farm. We are also looking for volunteers to help maintain the labyrinth or those interested in roses that want to admire and help deadhead the plants. Signup for U-Pick and check the website for all the ways to enjoy the farm. https://www.mariquita.com/features/lavender-u-pick/

The lavender field is our home and we have the well being of our neighbors to consider, so we are doing the U-Picks by reservation. Please don’t bring pets, even if they are in the car. The U-Pick is for Ages 8 and up only. A sun hat is highly recommended, as is a full water bottle. Thank you, and we hope to see you soon! Andy & Starr

Starr’s grand daughter is a great volunteer and a meticulous weeder.

Check this link if you’re interested in volunteering. https://www.mariquita.com/friends-of-ladybugs-labyrinth/

© 2023 Essay by Andy Griffin

Looking for a Few Good Gnomes

Ziggy on guard under a Rosa gallica complicata. This old fashioned rose only blooms once a year, but it’s a beauty and very resistant to disease.

So what if I’m a vulgarian? Having bad taste isn’t like having no taste at all. Besides, we’re not talking “Pink Flamingos” level bad taste here. But enough apologizing….I first met Ziggy, the Gnome, at a Nursery in Saratoga. He had clearly been passed over by the public and demoted by the store manager to a dusty corner in the back, next to a half pallet of 30 lbs plastic sacks of composted steer manure that had started to split and spill their contents. Ziggy’s once prominent spot on the sales floor, right by a bright display of bedding plants, had been taken up by a rainbow tribe of colored, cherry faced, hollow, plastic garden gnomes that exuded a sugary, Disney vibe. Ziggy may have been placed in a dark, dusty corner, and one corner of his concrete pedestal was broken, but he maintained his erect poise and projected the stern but benevolent gravitas that the younger, lighter, brighter gnomes could only aspire to achieve. I hired Ziggy immediately and installed him near our garden gate, where he stands as our 24 hour sentinel, shaded from the sun and moon by a large Gallica rose and an arching Nopal cactus.

A tasteful, larger than life, marble garden nymph, complete with snake, like this one at Villa Montalvo in Saratoga, will set you back a few dollars.

Garden gnomes weren’t always considered as kitsch by the sophisticated. The earliest Gnomes that we have records of date back to Central Europe in the 1600s, and they were like totems, carved from logs, painted, and situated by property owners to keep an eye on their lands. Some people say that the word “Gnome,” comes to us from Latin and they quote Paracelsus, the Medieval Swiss Alchemist, doctor, theologian, philosopher and wordsmith, who created the word “gnomus” as a synonym for “pygmy.” The ancient world had been populated by many magical, humanoid races like fairies and cherubs, but the Catholic Church had largely re-categorized these spirits as evil demons. In his magnum opus, “A Book on Nymphs, Sylphs, Pygmies, and Salamanders, and on Other Spirits,” Paracelsus redefined nature spirits to make them more compatible with Christianity and he wrote that gnomes were elemental creatures that moved through earth as a fish moves through water. Perhaps the word “gnomus” came to Paracelsus from the Greek “genomos,” meaning “from the earth.”

Armadillos lined up at a gift shop in Fredricksburg, a German colomny in Texas, just waiting to move to a garden. Your’s?

It’s worth noting that “Paracelsus” was not Paracelsus’s true name; by birth, the namer of the gnome was named Phillippus Aureolus Theophrastus Bombastus Von Hohenheim. That’s pretty German! Germany is where the first high volume manufacture of garden gnomes began too. In Dresden, the Baehr and Maresch Company began making ceramic gnomes for export as early as the 1840s. Some of these very expensive garden sculptures were imported to Great Britain by Sir Charles Isham to decorate the grounds of his mansion, Lamport Hall. For his time, Sir Charles was considered an eccentric; he was a socialist, vegetarian teetotaler who believed in gnomes and fairies. But he was rich, so a lot of people copied him. Sir Charles ignited a gnome trend among wealthy English landowners, and in time manufacturers began to produce more down-market gnomes for the masses too. Naturally, as more and more middle class gardens began to feature these newer “knock-off” gnomes lolling about the tulips in the suburbs, the fad came to be seen by the tastemakers as regrettable and vulgar, and people moved on to other motifs in garden art, like plastic flamingos or metal armadillos.

Tastes always change and styles must evolve and mutate just as viruses do, so ceramic garden gnomes could have completed a downward skid from the glare of popularity to the oblivion of the passe if it hadn’t of been for another wealthy eccentric, the English lawyer and microscopist, Sir Frank Crisp. In the late 19th century Sir Frank bought Friar Park, an expansive estate, and created a vast and spectacular garden with a scale model of the Matterhorn, and he populated the grounds with large, classic, ceramic garden gnomes from Baehr and Maresch. A new generation of gardeners copied him too, keeping the garden gnome culture back to life for another sales cycle. The two world wars were not kind to garden gnomes because they were perceived to be Germanic, like the Kaiser or the Fuhrer, and not so much benevolent and mysterious elemental creatures of the earth a la Paracelsus. Garden Gnomes could have been canceled again by the zeitgeist and the fashion fates except for….Meet The Beatles!

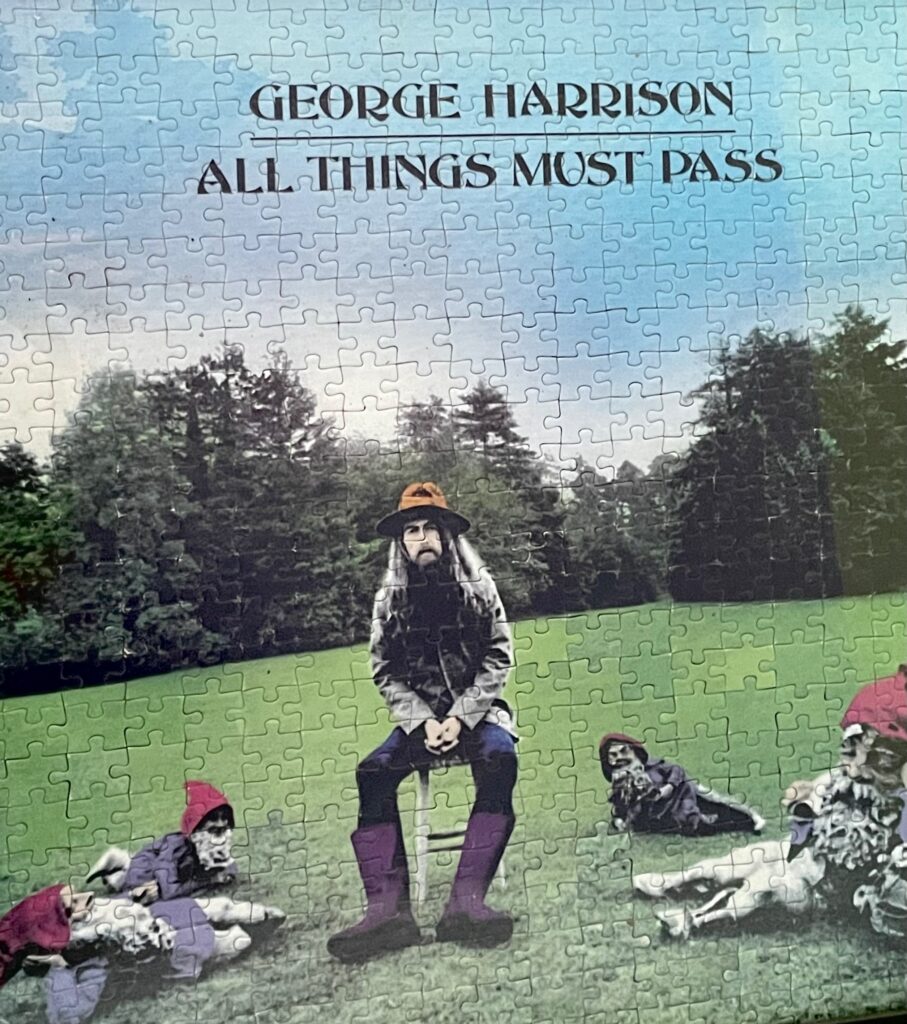

Sir George surrounded by the OG Gnomes of Friar Park that were brought from Germany by Sir Frank Crisp.

John, Paul, George, and Ringo- the Fab Four- made a lot of music and a lot of money for a lot of people in the 1960s. And as their roller-coaster ride of fabulosity came to an end, George Harrison, the Beatles’ lead guitar player, purchased and refurbished Sir Frank Crisp’s decaying Friar Park mansion with its expansive grounds and luxurious gardens. Harrison came to love gardening, and in time he came to think of himself as a gardener who played the guitar and “had a few hits” rather than as a rock and roll star. On his first solo album, All Things Must Pass, Sir George chose a photograph of himself on the lawn at Friar’s Park, surrounded by Crisp’s classic Maresch garden gnomes for the cover art. As a kid I was a Beatles freak, and Harrison’s record was how I first became aware of garden gnomes. In time I’d become a farmer and gardener who plays a little guitar, and it only seemed natural to give a nod to my musical hero by finding a home in the garden for a gnome. Ziggy is a concrete gnome, not an expensive ceramic medieval gnome, and we got him for half price because he had a cracked footing, but he still fulfills the traditional role of casting a protective eye over the garden. I have not achieved the alchemical perception that allows me to see gnomes moving through the earth as fish through water, like Paracelsus, but I do believe that soil is a magical medium full of organisms and symbiotic, alchemical and mysterious processes. We are only at the beginning of learning how complex and sophisticated the life of the soil is, and I suspect that as we become wiser about the earth’s ways, elemental creatures like gnomes are going to seem a lot less outrageous than they may now. Starr and I don’t have the resources of Sir Charles Isham, Sir Frank Crisp, or Sir George Harrison, but we are eccentric and we have been blessed with a gorgeous scrap of earth to care for. Our efforts to create a beautiful and diverse garden-scape above ground has already led to an increasingly active landscape, with birds and frogs, lizards, butterflies, bees and ladybugs abounding.We’re creating a large and lovely and meditative garden setting that we can share with others. If you’re sympathetic with this vision, or if you just want to get out in the fresh air and do some gardening to clear your mind please consider taking a shift as a volunteer “garden gnome.” We won’t make you stand guard all night by the cactus, like Ziggy, but he will be keeping an eye on you. We’re especially looking for help weeding in the lavender labyrinth to keep the labyrinthine passages clean and easy to walk, and we can use some help “deadheading” the roses and clipping the lavender too. If you would like to try your hand as a garden gnome, helping Ziggy to maintain the calm, beauty and order of a meditative garden, please reach out to us at https://www.mariquita.com/friends-of-ladybugs-labyrinth/ We ask that any volunteers be 18 or over and that they not bring any pets with them.It’s a farm, so expect a certain amount of dust or mud and dress accordingly with sturdy shoes.

A bee working hard in Ziggy’s Rosa gallica complicata

Again, we do have bees, so “bee aware” please. The bees have a lot of work to do, flying about gathering nectar and distributing pollen, so they are typically too busy to bother with us and they have a peaceful spirit but “Bee-ware” and give them their space. Bring a hat, sunscreen, water, and snacks. Bring a jar too- you may want to take home some flowers too.

If you’ve got your own garden to care for you might be interested in our “Create A Garden Stepping Stone” event, with local crafter, Jewel Rogers. https://www.mariquita.com/product/create-a-garden-stepping-stone/

© 2023 Essay by Andy Griffin

Walk for Peace

My late dog, Red, helping me research labyrinths. This one is on the coastal bluffs of Santa Barbara

Starr at the hidden labyrinth near the Golden Gate

His command of English was way better than my Japanese, and I respect that, so I hope he didn’t think I was laughing at him. But when Akira visited our farm last summer and looked out over the 110-foot diameter coil of raised beds of lavender dug into the middle of our field, one of his first questions was, “What for, plant in labyrinth?” I smiled and came up with a glib answer that amused me. “Because,” I replied, “after 40 years of commercial row crop farming I’m bored with planting in straight lines.” Akira was touring a range of farms in California and studying their operations as a way of preparing himself to start out his own farm back in Japan and he dutifully recorded my answer in his notebook. I laughed, but now I’m beginning to wonder if maybe the joke wasn’t on me. Months later, Akira is back in Japan starting his own farm and I’m still thinking about that moment, because his question was a good one, and it’s one I’m challenging myself today to answer in a more thoughtful way. Starr and I are inviting the public to come on May 6th and walk the labyrinth that we’ve created as part of “World Labyrinth Day” and I can expect any visitor to ask the same question. So why did I “plant in labyrinth?”

A labyrinth is different from a maze. A maze can be a puzzle path with false starts, dead ends, surprises, and ambiguities. You can get lost in a maze. A farmer might plant a corn maze and charge people a small fee to enter and have fun. You might even be lucky to get out of some mazes alive. Some people say that a maze is a metaphor for life and that we often stumble through our days confused and disoriented. A maze can provoke you to ask yourself, “Where am I going?” George Harrison once sang “If you don’t know where you’re going, any path will get you there.” So what path are you on? Where are you going?

The “before ” shot of the labyrinth field

Some visitors have chosen to arrive by air!

By contrast to a maze, a labyrinth has one pathway that – if you follow it long enough- will lead to a center. The labyrinth’s path may appear at times to lead away from the heart or loop back on itself but, if you have the discipline to keep going, if you don’t get tired or bored and quit, you WILL reach the center. Some people say that a labyrinth is a metaphor for life. The labyrinth that Starr and I have made is modeled on the Chartres Cathedral labyrinth that was built in the Middle Ages. But labyrinths have been created by many religious traditions over millennia as meditation tools for spiritual development. Starr and I got started on building and planting our labyrinth when the Covid plague shut down the farm for a while, and the construction certainly kept us busy. Now, after three years, the digging is done, and young lavender plants are beginning to fill in the borders. We invite you to come and walk the labyrinth. Maybe you have questions about the path you’re on and the scent of lavender in the air and sound of the birds singing in the trees may provide some inspiration. Maybe you know where you’re going and you just want to detour down a curving country path and enjoy the roses, cacti and lemon trees that frame the labyrinth. Or maybe you just want to get off of 880 or 101 and sip some lavender lemonade and calm down.

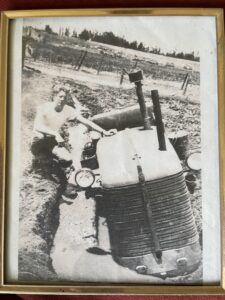

When I was a child the field where Starr and I situated the labyrinth was my grandfather’s sheep pasture. My Grandpa Graydon was born in 1892 and he was a farm worker all his life. He was in that bridge generation from the past to the present and he could drive a team of mules, do basic blacksmithing, repair a gas powered engine, shoot to kill, butcher a sheep or a cow, and grow any vegetable, fruit tree or grain. He lived through two World Wars, several economic depressions, and the Spanish Flu epidemic. He kept going when his sisters died from tuberculosis and he didn’t lose hope when his own children got sick with TB or got sent off to war. My grandpa lived to see Neil Armstrong land on the moon, but he was a practical, “down-to-earth” man of his time, and he had an abiding faith in hard work, in Jesus, and in chemical fertilizers, herbicides and pesticides brought to us by progress and Dow Chemical. I admired my grandfather immensely.

My father as a young man on a ranch somewhere in the Salinas Valley

My father wouldn’t have played much in the field where the labyrinth is now planted because he was bedridden with TB when he lived here. When my dad was healthier, the family lived on other people’s ranches where his father worked as a ranch hand. This place was never enough of a farm to support them. Dad got lucky. He was a veteran of the Korean War and the GI Bill helped him get out of the fields and make his way through college all the way to a Ph.D in Botany. Dad was in that first generation of botanists that looked past the Victorian Era’s Imperialist obsession with “discovering” plants that had been known and utilized by “natives” for millennia and then naming them after themselves. My father thought of himself as a plant ecologist and he and his peers looked at the world holistically as an interrelated web of life where plants and animals and fungi were symbiotically dependent on each other. In an era where humankind could shoot itself into space and look down on the earth, the ecologists were here to echo the wisdom of the first peoples and remind us that we are never above or apart from our relationship and dependence on all other living things. I admired my father immensely.

Maybe I’m lucky. From the time I was 14 I had a sense of the pathway that I am on. Some people look for years to find a sense of direction. I grew up on a rural University research station for Cal Berkeley, surrounded by scientists of every stripe, as well as that crazy blend of hippies, cowboys, Indians, peaceniks, rednecks, Sikhs, and Buddhists that made up the social collage of upper Carmel Valley in the 60s. From my grandfather and my ranching neighbors I got a love of agriculture and a sense and acceptance of the uncertainty that depending on nature for a livelihood can mean. From my father and the liberal minded Berkeley ecology students that I was surrounded by I absorbed a love of untamed nature, a faith in the scientific method to deepen our appreciation for our place in creation as one organism among many, and a loathing for the smell of pesticides and the indiscriminate damage to the ecosystem posed by unrestrained commercial exploitation of natural resources. It took me a while to discover the appropriate vocabulary to describe the path I’m on, but I knew I wanted to do it all- to raise food and make an honest living off the land but in a way that honored both my father and my grandfather and respected the land we all love.

I’m 63 now, so I can look back with a sense of perspective about the path I’ve taken. Sometimes my life has seemed like a maze, but now, with the benefit of age and experience I can see that what seemed like dead ends or false starts turned out to be curves. I once worked for the Cargil Corporation as a field worker and got sprayed by an airplane in the sunflower fields. What could have been a good moment to quit agriculture became a catalytic event to move me further to the left. I found a summer job working on a little biodynamic garden that served Chez Panisse and I earned five dollars an hour. I also found my tribe of people who were working as a community to bring an environmental and social consciousness to the food system. My work gave me a chance to meet visionary and energetic people like Albert Straus, Ellen Straus, Warren Weber, Amigo Bob Cantisano, Mollie Katzen, Patty Unterman, Judy Rodgers, and Alice Waters. With the help of my late wife, Julia, I was able to buy this property from my family, and she built the community-centric business that allowed us to raise our own family here. She and I named our farm “La Mariquita,” meaning “The Ladybug” in Spanish, because our goal was to create a farm that was small and beautiful where the ladybugs were welcome partners.

Starr and her son, Malakai, planting the labyrinth

Family farming in a healthy and life affirmative way has never been harder, but it has never been more important either. For me, constructing a huge labyrinth and planting it out with beds of lavender is a life affirming artistic statement, like a spiritually suggestive crop circle that you can see if you’re flying over the world’s problems in a jet on your way to your big conference in Silicon Valley. I’m not against high tech- I’m writing this on a computer- but it can be too easy for the innovators and policy makers to get lost in the seduction of virtual reality and forget the actual reality of earth, air, fire and water down here in flyover country. I think of our labyrinth as a beautiful hello emoji looking up from the land. “Hi Jet plane people. What path are you on? What path are you taking us down?” And besides being a symbol and an invitation, the labyrinth is also a crop producer. Starr has been gathering and drying the lavender flowers. We’ve planted beds of roses and lemons and culinary herbs to embrace the labyrinth, and these crops yield their harvests in their seasons. Plus, farming in straight rows WAS starting to get to me. I wasn’t lying when I told Akira I needed a change, and I feel better for making it.

Shelley’s “wabi-sabi” rendering of our vision for the labyrinth.

Starr has her own reasons for working with me to create this gigantic earth art piece, and I’ll let her speak for herself. But I can tell you a few things about her that might put her energy into perspective. She’s the one in the family with an actual degree in Plant and Soil Science. Now she’s a farmer, but she was an organic activist and organizer back when the conventional agriculture crowd greeted those efforts with real hostility. These days, those same companies own the largest organic farms, but that’s a story for another day. And when Starr’s days as an organic farm inspector were in the rear view mirror she focused on event organizing and worked as an artist creating custom pocket shrines for people. Starr and I share a vision of the farm and labyrinth as a living, flowering, fruiting, buzzing, chirping, sweet-scented earth shrine to Mother Nature. When you enter through the front farm gate – or fly overhead- it’s our hope that your first reaction is “Holy Compost! This place is ALIVE!” And we hope it makes you feel more alive too, no matter the path you’re on.

Treat yourself to a special day on Saturday, May 6th when we walk with others around the world for “World Peace” in the Labyrinth. We will also tour the gardens and talk about roses; we have over two hundred rose plants now. And our friend Danielle, a local esthetician and owner of Wild Beauty Cosmetics, who has been buying and using our roses to make rose oil, will do a special rose oil tutorial. All that, and lunch will make for a memorable day at Mariquita Farm. Space is limited and you won’t want to miss out. Tickets available below at:

https://www.mariquita.com/.product/world-labyrinth-day./.

Here’s a link to Akira’s farm blog if you want to see what he’s up to blog: https://agri-step.info

You can also keep an eye on what’s coming up via our two Facebook accounts, Mariquita Farm and Ladybug’s Labyrinth and Secret Garden and you can find us on Instagram @mariquitafarm or @ladybugslabyrinth.

Andy and Starr

© 2023 Essay by Andy Griffin

Photos by Starling Linden & Andrew Griffin

Finally some sun!

My grandmother once had a cat who had three kittens on the 15th of April. Naturally, she named them “Taxine,” “IRiS,” and “Deadlina.” But April 15th means different things to different people. For those of us who farm along California’s Central Coast, April 15th is our “frost free” date. Obviously, there’s nobody to sue if Mother Nature chooses to send a frost our way on April 16th, and I do remember a hard frost on April 17th back in the late ’90s but, generally, we are out of the coldest weather by mid April.

Here is the crop of Austrian Winter peas that we planted as a cover crop. The ground has finally dried out enough to work so we turned the peas under on Monday. A legume cover crop has converted as much atmospheric nitrogen into a soluble form that plants can take up when it has started to flower, so when we see the blooms we get ready to disk the foliage under. Besides adding nitrogen to the soil a good cover crop adds lots of biomass, which breaks down into carbon particles, which aid in water retention. I managed to get a first row of seedlings transplanted too. Here are some baby sunflowers I got into the ground. Artichokes are next.

Next to the sunflowers you can see the wire mesh that the beans will climb up. I planted perennial runner beans last year, and as soon as the soil warms up we will see the underground tubers push up the shoots of this year’s bean crop, so there’s no need to plant them- I just have to weed the rows so that the slugs and snails don’t destroy the emergent stems and leaves.

Besides working the soil and getting the transplants out we’ve got a lot of winter related remedial damage control to get through.  A big eucalyptus fell over, covering my rototiller, box scraper, and disk harrow, as well as crushing a harvest wagon. Also buried were beds of oregano, sage, sorrel, borage, mint, and fennel. Before it was chopped up the tree reached all the way from the leaves in the foreground to the trunk on our neighbor’s property. But we now have firewood for life!

A big eucalyptus fell over, covering my rototiller, box scraper, and disk harrow, as well as crushing a harvest wagon. Also buried were beds of oregano, sage, sorrel, borage, mint, and fennel. Before it was chopped up the tree reached all the way from the leaves in the foreground to the trunk on our neighbor’s property. But we now have firewood for life!

The wind can be problematical, but all the rain has been good for our citrus orchards. Our lemon trees are so loaded down with fruit that the branches are at the point of breaking. Thanks to our friends at The Dream Inn, in Santa Cruz, we’ve been able to harvest a lot of lemons for their kitchen. Here Starr looks down on me, picking from above, as I lie on my back and pick from below. Each “dwarf” Meyer lemon tree has been yielding 100 lbs of lemons. We have many specialty varieties of young citrus trees that have appreciated the copious rain that came our way this winter and they’re growing like crazy.

Given all that has transpired over the last several years we are not in a position this year to deliver regular boxes of mixed veggies, fruits and herbs, as we have in the past, but we will resume a schedule of pop-ups when we have the crops to back them up, and we will be opening the farm for a series of events, u-picks, and workshops. Join us Saturday, May 6th, to celebrate World Labyrinth Day with a Labyrinth walk, a tour of the farm and rose gardens, and a presentation by Danielle Kingsley of Wild Beauty Cosmetics about the skin care products she makes from our rose petals. Keep an eye on the newsletter for details. Here I am in a shadow selfie waving “goodbye” to a long, hard, cold, wet winter and “hello” to you all and a fruitful, floral, and flavorful season.

Thank you for reading our newsletter. To keep current with the happenings on the farm please follow us on Facebook @ https://www.facebook.com/MariquitaFarm and https://www.facebook.com/LadybugsLabryrinth/ We manage our Instagram accounts so that they have different content from Facebook. Follow us on Insta @mariquitafarm and @ladybugslabyrinth

PS- The tomato plants are waiting until April 15th to go in the ground. No use taking chances with something so important.

Thanks, again. Andy and Starr

© 2023 Essay by Andy Griffin

Mariquita 2.0

Have you noticed that God didn’t create “The Farm of Eden?” It’s one thing to imagine walking in a garden naked with your lover like Adam & Eve did, innocently sharing ribs, sharing fruit, caught up in the enchantment of nature. But a farm? It’s not the same vibe to wander around an alfalfa field in your birthday suit, or a cattle feedlot, or a cabbage patch. Besides, if we are to take the Book of Genesis literally, farms are “cursed ground.” By the end of Chapter Three, God has kicked the first couple out of Eden and we’ve all had to live in exile, “by the sweat of the brow,” ever since. Farms are work. Farms are all about production, harvest, sales, shipping, payables, receivables, payroll, regulations, taxes and either avoiding, surviving, or ameliorating the vagaries of weather.

I don’t buy into the notion that my career in agriculture has been a curse but, like Adam’s first son, Cain, I am a farmer, and sometimes agriculture can feel punishing. The last several years have been an especially challenging rollercoaster ride for many businesses, with all of the disruptions provoked or aggravated by the Covid 19 virus, and life on our little farm has been no exception. But there has been one benefit to all the plague drama; Starr & I got to devote a lot more time to our home garden. With every other distraction closed down or restricted, there wasn’t much else to do but garden when we weren’t working on the farm. And now, after three years, as the pandemic slowly morphs into a “new normal,” the gardens on our home ranch shine like they never did before and our work is beginning to pay off in blossoms and fruit. Our place can’t be The Garden of Eden, but we can aim towards planting a paradise, and we’ve even found homes for a couple of colorful, decorative, little talavera pottery snakes amongst our flowers, just for fun.

I don’t buy into the notion that my career in agriculture has been a curse but, like Adam’s first son, Cain, I am a farmer, and sometimes agriculture can feel punishing. The last several years have been an especially challenging rollercoaster ride for many businesses, with all of the disruptions provoked or aggravated by the Covid 19 virus, and life on our little farm has been no exception. But there has been one benefit to all the plague drama; Starr & I got to devote a lot more time to our home garden. With every other distraction closed down or restricted, there wasn’t much else to do but garden when we weren’t working on the farm. And now, after three years, as the pandemic slowly morphs into a “new normal,” the gardens on our home ranch shine like they never did before and our work is beginning to pay off in blossoms and fruit. Our place can’t be The Garden of Eden, but we can aim towards planting a paradise, and we’ve even found homes for a couple of colorful, decorative, little talavera pottery snakes amongst our flowers, just for fun.

Over the last three years we have planted over a hundred citrus trees, and set out at least one hundred rose bushes. We’ve set out beds of ornamental and culinary herbs, we’ve created floral walkways, planted redwood trees, and erected frames for heirloom Mexican crops like Hoja Santa, chayote, and perennial beans. We’ve tucked a kaleidoscope of ornamental sages and succulents into the corners and crannies of the garden, and established hedges of fruiting cacti. Our most sustained effort at gardening has probably been the construction of a raised bed Eleven Circuit Medieval Labyrinth, modeled after the labyrinth at the Chartres Cathedral in France, but we have planted ours out with several thousand aromatic lavender plants. And now, after all our work and the passage of time, the garden is really starting to come together. We’re calling this project “The Ladybug’s Labyrinth and Secret Garden.” It’s our goal to share our creation with the hummingbirds, butterflies, bees and ladybugs that are so much at home here in this quiet and beautiful setting…. and with you!

Over the last three years we have planted over a hundred citrus trees, and set out at least one hundred rose bushes. We’ve set out beds of ornamental and culinary herbs, we’ve created floral walkways, planted redwood trees, and erected frames for heirloom Mexican crops like Hoja Santa, chayote, and perennial beans. We’ve tucked a kaleidoscope of ornamental sages and succulents into the corners and crannies of the garden, and established hedges of fruiting cacti. Our most sustained effort at gardening has probably been the construction of a raised bed Eleven Circuit Medieval Labyrinth, modeled after the labyrinth at the Chartres Cathedral in France, but we have planted ours out with several thousand aromatic lavender plants. And now, after all our work and the passage of time, the garden is really starting to come together. We’re calling this project “The Ladybug’s Labyrinth and Secret Garden.” It’s our goal to share our creation with the hummingbirds, butterflies, bees and ladybugs that are so much at home here in this quiet and beautiful setting…. and with you!

The pestilence of Covid aside, agriculture is never a stroll through the garden, and it never has been. Farmers who persist at their occupation learn to change their operations and adapt to the economic environment as marketing conditions change around them, just as they have to react to the weather. The now typically and predictably insane weekday traffic across the Bay Area has made our old delivery model of business problematic, so one of the adaptations we’ve made at Mariquita Farm has been to move towards a garden scale operation that is more of a destination for people to come to us. I’m thinking of this new effort at serving the people as Mariquita 2.0. Yes, we will continue to offer our produce to consumers through a series of pop-ups around the Bay Area, as we have in the past, but we will be focusing those outreach efforts on the summer and fall months when we can count on your favorite harvests of dry-farmed Early Girl tomatoes, and colorful heirloom and cherry tomatoes to go along with the herbs and flowers.

New on the farm this last year was an addition of the onsite Ladybug Gift Shop where we feature all of our dried herbs, heirloom beans, corn and flowers, along with a collection of gifts, plus a variety of plant starts that we have grown, including both edible and ornamental plants. For those folks who are further away, or for mailing our farm products and gifts to friends and family out of the area, look for our new mail order possibilities on the website this spring. Also, on the farm for the 2023 season, we will host a series of exciting workshops on a range of activities-everything from ice-dyed clothing, amazing copper stone and gem wand making, to stepping into your garden with your very own hand-made stepping-stones. Flowers will be abundant on the farm this summer and you will be able to come and make a variety of flower bouquets. Visit us and walk the Labyrinth on World Labyrinth day, May 6th when we will host a labyrinth tour. And… if you have your own party ideas, anything from company staff parties to bridal or bachelorette parties, or if you want a place to host your workshop, our farm can be your farm for a day! Look for all the new exciting details on how to host an amazing farm event with your family and friends.

New on the farm this last year was an addition of the onsite Ladybug Gift Shop where we feature all of our dried herbs, heirloom beans, corn and flowers, along with a collection of gifts, plus a variety of plant starts that we have grown, including both edible and ornamental plants. For those folks who are further away, or for mailing our farm products and gifts to friends and family out of the area, look for our new mail order possibilities on the website this spring. Also, on the farm for the 2023 season, we will host a series of exciting workshops on a range of activities-everything from ice-dyed clothing, amazing copper stone and gem wand making, to stepping into your garden with your very own hand-made stepping-stones. Flowers will be abundant on the farm this summer and you will be able to come and make a variety of flower bouquets. Visit us and walk the Labyrinth on World Labyrinth day, May 6th when we will host a labyrinth tour. And… if you have your own party ideas, anything from company staff parties to bridal or bachelorette parties, or if you want a place to host your workshop, our farm can be your farm for a day! Look for all the new exciting details on how to host an amazing farm event with your family and friends.

All of the details on our events and farm day-use will be presented on our newly designed website coming out later in March. You can also keep an eye on what’s coming up via our two Facebook accounts, Mariquita Farm and Ladybug’s Labyrinth and Secret Garden and you can find us on Instagram @mariquitafarm or @ladybugslabyrinth.

We are very excited about these changes and we hope you will be too!

We want to thank each and every one of you for your loyal support as hosts and customers over the many years in our CSA. Our hope is to continue the relationship by offering you an opportunity to visit us here on the farm and to come out when we have pop-ups in your area.

Here’s to a wonderful 2023

Andy and Starr

© 2023 Essay by Andy Griffin

Photos by Starling Linden

Hope Springs Eternal

I’ve got a counterintuitive tale for you. Several years ago, during the driest, dustiest, saddest period of the last drought, I was gazing out the kitchen window to the north, across the fields and towards the Santa Cruz Mountains. From the valley floor to the top of Loma Prieta and Mount Madonna the land was faded, tired, and sad. But the lone Live Oak in the middle of the field just below my house seemed particularly droopy, as if it were losing leaves. I wondered if maybe the Oak Moths were getting to it so I wandered down the hill to check it out. I drew close to the weeping oak and I was looking up into the branches, expecting to see a cloud of Oak moths fluttering about or a swarm of their caterpillar larvae eating at the leaves, when I suddenly sank in mud up to my ankles. The ground under the dying Live oak was sopping wet. In the middle of the drought we had a puddle in our field. I looked back up the slope towards our house and my gaze settled on our windmill that stood still and quiet…

Oak tree (before).

We got electric power here on the ranch back in 1956 and my grandfather chose, at that time, to switch from wind power to an electric pump to draw our water from the spring box. The old windmill had worked fine to bring water to the surface and maintain an animal trough, but it couldn’t push the water up the hill to the house, and at any rate our field is sheltered and we don’t have a lot of wind. The old well isn’t deep either. My great grandfather, Marius Jorgensen, built it by digging a deep hole. He was a mason by trade, schooled in Denmark, and he did his work “Old School” style by laying a ring of brick around himself as he dug the hole until he had excavated a cavity 10 feet wide and 20 feet deep and lined it with bricks. Water seeped between the bricks and rained into the cavity until the well was filled. Of course, there were snails in there, and salamanders and god-knows-what-else swimming in the water, but we drank it. When I got married my wife, Julia, took one look at the well and said, “No Way. I’m Modern!” So we had a domestic well dug next to the house that was 250 feet deep, with a concrete collar around the well shaft to eliminate the danger of any surface water contaminating the deep aquifer.

Oak Tree (after)

The water seeping into our old spring box down the hill from the modern well is surface water- it seeps out from springs from a local and shallow Santa Cruz Mountain aquifer that rides on top of the deeper Sierra Nevada aquifer. If you look out across the valley from our place you can see stands of willow trees growing along the hills, all at the same elevation above the valley floor, marking where the land drops from this surface aquifer so that the native water bearing layer is exposed and shows itself as a series of springs and seeps. When Jack Edsberg drilled a new well for me in 1994, the tailings from under the bore hole showed us that the drill bit chewed through 200 feet of pure clay to reach the gravel beds and underground rivers of the second, deeper aquifer. Since we first started pumping from the new, deep, well for domestic use our water table has fallen at a rate of about a foot a year. This is not good news. We still have a standing column of water 100 feet deep to draw from, but at this rate we are game-over for water in a hundred years. But, paradoxically, our local watershed that overlays it is releasing more water through the springs on our property than it did in the recent past. The ailing oak tree was drowning in a drought.

Once we had our new, domestic pump to serve the house, I was free to use all the spring box water on my farming projects. I installed a 5000-gallon water storage tank at the top of the hill, to hold the spring water for fire protection and light irrigation. And for years I did grow a modest few beds of herbs at the home farm and I began planting citrus, roses, and cacti. Maybe it was one of our local earthquakes that moved some subterranean rock around and opened up some new springs to flow on our land. Since I clearly now have enough new water to drown an old oak tree I figured I could use another storage tank. We got the new tank installed this past summer. Now, with 10,000 gallons of water storage, I feel comfortable that I can maintain a much more serious effort at farming this land than I have in the past, and for the past year we’ve been gearing up our efforts at production here This year we were able to finish the labyrinth that we dug by hand and planted out with lavender. And in 2023 we get to see the first mature bloom set. And the remarkable thing is that the lavender, a drought tolerant crop, uses very little water.

Around the edge of the field with the labyrinth I planted a hedge of nopal cacti, interspersed with roses. I was fortunate, a few years back, to be gifted cuttings for 15 different kinds of prickly pear cacti by a member of the Rare Fruit Society. As they mature and begin to produce their fruits the range of colors of the fruits will become obvious. There are “prickly pears,” or “tunas,” in Spanish, that are purple, red, rose, orange, yellow, white, and green. The different varieties of nopal cacti yield their crops at different times of the year, and their fruits taste different and lend themselves to different uses. The purple cactus fruits are known to the Italians as “Fico d’Indio,” or “Indian Figs,” and they are much appreciated for their use in flavoring and coloring lovely granitas and sherbets. Purple cactus syrups are great for coloring drinks too.

Around the edge of the field with the labyrinth I planted a hedge of nopal cacti, interspersed with roses. I was fortunate, a few years back, to be gifted cuttings for 15 different kinds of prickly pear cacti by a member of the Rare Fruit Society. As they mature and begin to produce their fruits the range of colors of the fruits will become obvious. There are “prickly pears,” or “tunas,” in Spanish, that are purple, red, rose, orange, yellow, white, and green. The different varieties of nopal cacti yield their crops at different times of the year, and their fruits taste different and lend themselves to different uses. The purple cactus fruits are known to the Italians as “Fico d’Indio,” or “Indian Figs,” and they are much appreciated for their use in flavoring and coloring lovely granitas and sherbets. Purple cactus syrups are great for coloring drinks too.

Starr harvesting rose petals.

There’s a logic to planting roses too. I’ve come to appreciate how hardy roses are. I like plants that can survive the sometimes-long stretches of time when I’m too preoccupied to pay much attention. Roses respond well to care, and sometimes they can benefit from a period of benign neglect. At present we’ve got about a 100 roses planted and It’s been nice to see these plants start to flourish. Starr has been harvesting fresh petals for a local aesthetician, Wild Beauty Cosmetics, in Soquel, and dried petals for the Dream Inn Romantic Room Package, in Santa Cruz. The fun thing about harvesting petals is that we get to enjoy the roses before we need to harvest them. Against the western edge of the field, which I feel is too shady for good cacti habitat, I switched from interspersing cacti with roses to planting a row of solid roses. But these are all climbing roses that can scale the young live oaks that border the field and, in time, provide a dramatic backdrop of color to embrace the labyrinth and milpa that take up the flat ground.

The lemons and other citrus that we’ve planted on the slope behind the labyrinth are greedier for water. Citrus trees are usually grafted trees; there’s a sturdy rootstock of a citrus variety that is valued for vitality and disease resistance, upon which are grafted the valuable commercial varieties of fruit bearing variety. When a citrus tree is stressed for water it has seemed to me that the vulgar, spiny rootstock responds by sending up new shoots and overwhelming the scion that’s been grafted to it. After three years in the ground I see the most recent citrus plantings starting to really thrive and it makes me feel good. We’re already getting lots of lemons, and now the limes are beginning to kick in, and there are Buddha’s Hands from time to time. Next year will be the year that the other varieties of citrus catch up and begin producing meaningful harvests. We’ve got yuzu, limequats, finger limes, Rangpur limes, and blood oranges planted- and flowering.

Looking into a bucket of cover crop seed.

It’s raining as I write this note, and it makes me glad that we got our cover crop in just before the storm hit. Thanks to our hardworking volunteers Arnie & Linda for helping us scatter the seed across the tilled field, just ahead of the raindrops. Next year I plan to flip the planting scheme around so that the ground that had marigolds on it this year will have the milpa, and vice-versa. The milpa was a lot of fun, and productive. We harvested a lot of corn and squash. Next year I plan on milpa that uses Otto File corn, Rugosa squash, and Italian runner bean for a fun Italian spin on the traditional Mexican planting scheme- as though the garden were planted along the Oaxacan-Sicilian border.

We built a small greenhouse to grow seedlings in, and sowing trays of vegetables along with a larger focus on flowers in 2023. For now, the last crops of 2022 are getting harvested and the fields are getting put to sleep for the winter.

We hope you will enjoy the last of the fruit and vegetable harvest along with our great stocking stuffers of dried herbs, herbal “tea” infusions, lavender and rose gifts, herbal cooking salts, jars of marmalades, beets and curried cauliflower and all the other delightful items we have left to offer. And don’t forget you can send some of these wonderful items to friends all over the country with our gift packages or order them for pickup at your site making it a happy holiday filled with farm gifts for everyone.

We hope you will enjoy the last of the fruit and vegetable harvest along with our great stocking stuffers of dried herbs, herbal “tea” infusions, lavender and rose gifts, herbal cooking salts, jars of marmalades, beets and curried cauliflower and all the other delightful items we have left to offer. And don’t forget you can send some of these wonderful items to friends all over the country with our gift packages or order them for pickup at your site making it a happy holiday filled with farm gifts for everyone.

Thanks,

Andy, Starr and the Crew at Mariquita Farm

© 2022 Essay by Andy Griffin

Photos by Andy Griffin and Starling Linden

There’s More to the Story

“Every picture tells a story” they’ll tell you. And it’s probably “a thousand words” long, too, if the clichés are to be believed. But I wonder if maybe it isn’t the frame that’s the most important part of any picture? How you choose to frame an image both limits and focuses any intended expression. Another person, finding themselves in the same circumstances with the same camera as you, might react with a snapshot that tells an almost entirely different tale simply by framing the moment from a different perspective. One of my favorite pictures that I took this year was of Kelly waving up at me from inside the marigold patch. The image captured a moment of joy and color for me, and it confirmed all the choices I’d made about what kind of marigolds to plant and when to plant them. We were inspired to plant a marigold crop to coincide with Diwali and Dia de los Muertos festivities and, with some friendly mentoring from our friends at Arnosky Family Farm in Wimberly, Texas, we got the right seed, planted it at the right time, and totally nailed the moment. The flowers were fun to grow, beautiful, aromatic, and catalytic too, because they prompted us to meet some new people and engage with new communities.

A different perspective of the labyrinth.

A different photographer visiting the farm might have focused on an entirely different scenario. If you choose to employ a wide angle setting, you can paint an entirely different picture than that of a young woman smiling in a field of gold. A wider perspective can take in the labyrinthine pattern of garden bends dug into the field just beyond the marigolds and planted out in lavender. From above, looking down on the field from a bird’s eye view it might look for a moment that there was a crop circle carved into the land. But there’s nothing alien about this labyrinth; Starr and I created it ourselves as our homegrown Covid project to broadcast some positive energy back at the world around us. Labyrinths are mysterious. We chose to model our homegrown labyrinth on the eleven circuit labyrinthine mosaic that was set into the floor of the Chartres Cathedral in France back in the Middle Ages. We bordered our labyrinth’s path in lavender because lavender is a very hardy, drought tolerant, healing herb. This earth-art project has been a couple of years in development and execution and it felt good to get it finished this year. One of the fun things about the labyrinth is that our cats often come down to join us when we’re working on it. Here’s a picture of Samson, our apricot-blond dreamboat of a cat, watching us weed the lavender beds on a mild, fall afternoon. We look forward to inviting you down in the spring to walk the labyrinth when it’s grown out more fully and in full bloom.

Samson in the Lavender beds.

Corn silk in the milpa.

Sometimes I’ll go on Google Earth to get a satellite’s super-wide view down on the farm. The last time I checked NASA had not yet swept overhead to record the milpa that we planted to embrace our labyrinth garden. A milpa is a classic indigenous Mexican planting scheme where the “holy trinity” of corn, squashes, and beans that are planted out together. In the dream world of a perfect milpa, the squash spread out across the earth, with their broad leaves choking out any malignant weeds. The corn stalks poke up through the canopy of squash foliage and the beans twine up the corn stalks. Corn, squash, and beans make a well-rounded diet for the human body and the plants are complementary in the field too. In a perfect milpa the weeds are succulent purslanes, glaucous quantities, and purple, wild tomatillos, each a nutritious complement to field and body, and weedy only in the sense that these plants defy any attempt to discipline them. The milpa worked out well this year and I have plans for next year’s milpa already. We will switch out the marigolds and plant them where the milpa was this year, and vice versa. Marigolds make an excellent rotation crop for food crops as they tend to suppress soil pathogens. We will put the corn, squash, and beans where the marigolds grew this year. We’re putting a nitrogen fixing cover crop on this ground next week, before the next rain hits. For a fun twist on the classic Mesoamerican milpa logic we will use an Italian heirloom polenta corn called “Otto File” for the corn part of the equation, and an heirloom Italian hard squash, the Rugosa butternut, to stand in for the squash component, and Japanese runner beans to be the legumes that will complete the trinity. Think of next year’s milpa as a fantasy garden planted somewhere along the Oaxacan/Italian/Japanese frontier. We had a fun farm tour this year when we participated in the Open Farm tour, and we plan to repeat and improve upon that experience.

Greg and Gus from the Dream Inn.

In 2023 we are focusing on welcoming visitors to the farm for events and workshops. Opportunities for small groups of 60 or less people can rent the gardens for staff parties and meetings, workshops, weddings, divorce parties and much more. Starr and I were happy to host The Dream Inn, from Santa Cruz, early this fall when the kitchen put on a special meal for their partners and associates in the media. It was fun to break out my heirloom cauldron that my Grandma used to cook beans in, back when she was a ranch cook in the 1930s and 40s. Keep an eye on our newsletter for updates about upcoming events and workshops that we will host in the spring and summer. The rose gardens are a sight to see and we hope to showcase them in April and May. In the short term, after we return from a brief Thanksgiving break, we plan to have a few popups in December before the winter holidays.

The table is set!

Wishing you all a full table of bounty!

Andy, Starr and the Crew at Mariquita Farm

© 2022 Essay by Andy Griffin

Photos by Andy Griffin and Starling Linden

Giving Thanks!

Turkeys roaming in the labyrinth.

Every day is “Turkey Day” at Mariquita Farm….but Thanksgiving only comes once a year. We have resident flocks of wild turkeys that roost in the pines in the forest at the edge of our field. It’s funny to see them hopping from bed to bed as they traverse the hand-dug 11 circuit medieval labyrinth that we’ve created in the middle of the field. When Starr created a farm store by our front gate one of the hens was captured by her reflection in the glass until I chased her off and broke the spell. When the turkey chicks hatch in the spring we see the hens lead long trains of little, fluffy, golf-balls through the grass on their daily hunt for the bugs, seeds, sprouts and greens that make up their daily diet. At first, we might see over twenty chicks trailing behind the hens. Then we’ll see 18, then 15, then 9, or fewer. The woods here are populated with fierce creatures that love to eat turkey every day of the year. Wild turkeys may seem silly and stupid, but somehow they survive the Bobcats, coyotes, mountain lions, and foxes as a tribe to raise up another brood of turkeys for the following spring.

Turkey reflecting…

Thanksgiving has been positioned by America’s promotional wizards as “Turkey Day” because gratitude is harder to monetize than dead fowl. I appreciate Thanksgiving because, besides being a moment to gather for a meal with friends and family, it also marks the end of the year’s growing season on the farm and I know that I’ll have a couple of more restful months ahead of me before the merry-go-round speeds up again. We’re almost to Thanksgiving again and I’m thankful that we’ve had a year on the farm with lots of work, but no accidents or unseemly drama. It’s been another weird year’s ride through the Covid pandemic, with uncertainties abounding, but thanks to your support we’ve made it through the season, and we’ve got a fall harvest basket full of wonder to share with you for your Thanksgiving meal. We wish you a peaceful Thanksgiving.

Here’s our schedule:

Following Thanksgiving we will step away from our regular delivery schedule but we will do some December pop-ups as we approach the winter holidays. Here’s our tentative schedule for December.

Saturday, December 10, 2022 in Palo Alto

Thursday, December 15, 2022 in Berkeley

Saturday, December 17, 2022 at Piccino Restaurant in SF.

Tuesday, December 20, 2022 in Santa Cruz County and Los Gatos

Turkeys roosting…

The holidays are here and we hope that you will consider sharing our gift boxes of dried herbs and herbal infusions, heirloom beans and jarred beets, curried cauliflower, tomato juice, crushed tomatoes and marmalades with your friends and and family. We ship or we will drop off at a pickup location. We also have lots of lavender, rose petals and lavender florets to share before the year is over.

Thanks for support this year!

Your friends at Mariquita Farm!

Andy, Starr, Shelley, Kelly, Gayle, Gildardo, Rebeca, Fidel and Federico, Hose, Abisai, Claudia, Neftali, Ramone and Maria

© 2022 Essay and Photos by Andy Griffin

Chayote

A few of you might find the fierce looking chayote that I’ve put in your harvest share box to be somewhat alarming. Fear not! Beneath it’s seemingly hostile exterior the chayote is actually a mild-mannered, healthy, economical and tasty friend in the kitchen with a worldwide fan-base. In case you don’t already know the chayote plant by reputation or from personal experience, let me make a formal introduction:

Every plant’s leaf is essentially a solar panel, erected and unfolded with the express purpose of gathering the sun’s energy in order to power the growth, maintenance, and eventual reproduction of the organism. The chayote’s broad, flat, and soft, pliable leaf is a clue that it might be a fast growing plant, and indeed it is. Not only do broad, flat leaves capture lots of sunshine and provide the power for rapid growth in high light environments, they’re also useful for plants that are growing in lower light situations to capture any and all of the available photons, and we see that the chayote employs both strategies for survival. Chayotes evolved in the area we now know as Central America, especially southern Mexico, Guatemala, and Honduras. The Chayote is a sprawling creature, spreading out over any available ground while sending long, tendriled vines high into and through the canopy of nearby trees, emerging from the tangled branches that make up the roof of the jungle into the bright light just that much closer to the sun.

If leaves are “solar panels,” then tubers are “batteries.” A chayote vine may trail 50 feet up a tree to chase the sun but it is sending the energy it gathers down the tangle of its stems into a tuber buried under the ground. The tuber stores the sun’s energy in the form of sugar and starch. A tuberous growth habit is a typical survival mechanism for tropical plants that can experience sudden, unexpected frosts that will burn up tender, exposed foliage. Yes, the Central American ecosystem where chayote evolved is usually warm, humid, and sunny, but mountains are mountains, and every once in a while there’s a sudden, hard frost that stings the higher elevations. The chayote that gets burned to the ground by the cold can always stage a comeback by sending up new shoots from the buried tuber that was insulated by the protective embrace of the earth. Potatoes do this too; they’re from the tropical Andes where the inconsistency of the weather is the only “constant.”

Oaxacan Chayote

A wild chayote’s fruit is spiny, which tells us that there’s something tasty there to be protected. The chayote is in the squash family, the Cucurbitaceae, and the flesh of its fruit is dense and mild flavored. A mouse or wild boar might want to eat the chayote but the gourd’s stiff spines are not very inviting. The indigenous people who lived across the natural range of the chayote learned to peel the spines off and enjoy the flesh of the fruit either raw, sliced thin and made tender with lime juice or salt, or steamed, boiled, baked or grilled.Like its cousin, the zucchini, the chayote has a mild flavor that can serve as a “delivery vehicle” for any number of more emphatic and unctuous sauces like mole. Our modern name for the crop, “Chayote,” comes from the Nahuatle word, “chayotli,” but as the crop gained popularity and spread south into what’s now South America it picked up other names, like “Chuchu,” or “Cahiote.” The fruits were harvested and used like squash, the tendrils and leaves were used as greens and added to soups and stews, and the tubers were dug up and cooked like potatoes.

When the Spanish voyagers came to the “New World” the chayotes jumped aboard their sailing boats. Despite its many uses, the chayote was not initially welcomed back in Europe. Like other indigenous American crops that feature in the “Columbian Exchange,” like the potatoes, tomatoes, and chili peppers, the chayote was suspect because it was not mentioned in the Bible. Since it didn’t get a specific name drop in Genesis, doesn’t that mean that the chayote might not have been created by God, but rather by Satan?

Once their colonies were established the Spaniards gathered up once a year, the immense piles of silver, gold, and jewels that they robbed from their new American subjects, or dug with slave labor from American mines and loaded up their ships with the booty, setting sail for Asian ports where they would trade. The treasure fleet that left from the port of San Blas, in Nyarit, was called the Manila Galleon, because its first port of call was in the Philippines. Filipino cooks were unconcerned with chayote’s suspected Satanic origins and they took to crop fast. Tagalog for chayote is “Sayote.” From Manila the culture and appreciation of the chayote spread out across Asia. You know that little chunk of something white and unknown that was covered in sauce in your Chinese takeout and you ate it without worrying? Chances are strong that was chayote.

Once their colonies were established the Spaniards gathered up once a year, the immense piles of silver, gold, and jewels that they robbed from their new American subjects, or dug with slave labor from American mines and loaded up their ships with the booty, setting sail for Asian ports where they would trade. The treasure fleet that left from the port of San Blas, in Nyarit, was called the Manila Galleon, because its first port of call was in the Philippines. Filipino cooks were unconcerned with chayote’s suspected Satanic origins and they took to crop fast. Tagalog for chayote is “Sayote.” From Manila the culture and appreciation of the chayote spread out across Asia. You know that little chunk of something white and unknown that was covered in sauce in your Chinese takeout and you ate it without worrying? Chances are strong that was chayote.

I’ve started growing chayote under the influence of my foreman, Fidel, and the Oaxacans I’ve been working with. It’s been a fun crop to learn about. The trick for success in growing any plant is to learn where and under what conditions it evolved, and to mimic that setting as much as possible. If a plant germinates and feels “at home,” the chances are very high that it will grow successfully. We bury each chayote that we intend to grow in a gopher basket so that the pesky rodents can’t harvest before we do. We erect a frame of 4×4 posts cloaked in chicken wire to give the vines something to climb on, like the thickets of sticks that natural chayotes would encounter in a natural setting, and then we give the plantation a thorough, gentle soak every once in a while, just like the rains they would experience in their Oaxacan or Honduran mountain homes. The chayote plants seem very happy here.

I had a couple of Oaxacan women visit the farm the other day and do a chayote “U-Pick.” They prefer the spiny chayotes, which is the variety that they know from back home. We have several different kinds of chayote growing, including the smooth forms that are preferred in Asian markets. What I’ve noticed is that the spiny chayotes come first, and the spineless, smooth chayotes tend to take a couple of weeks longer to develop, even though they were all planted at the same time. Maybe I’m just dull and insensitive, but the several kinds all taste pretty much the same.

I had a couple of Oaxacan women visit the farm the other day and do a chayote “U-Pick.” They prefer the spiny chayotes, which is the variety that they know from back home. We have several different kinds of chayote growing, including the smooth forms that are preferred in Asian markets. What I’ve noticed is that the spiny chayotes come first, and the spineless, smooth chayotes tend to take a couple of weeks longer to develop, even though they were all planted at the same time. Maybe I’m just dull and insensitive, but the several kinds all taste pretty much the same.

I hope you enjoy eating the chayote as much as I have enjoyed growing them. You can use them almost anyway you would any other summer squash. I’ve enjoyed them in saute and dressed with lemon or lime juice. You can keep them in the fridge, but you don’t need to. They’re perfectly able to hang out at room temperature on the counter and you can enjoy them as weird vegetal sculptures before you cook them.

I hope you enjoy eating the chayote as much as I have enjoyed growing them. You can use them almost anyway you would any other summer squash. I’ve enjoyed them in saute and dressed with lemon or lime juice. You can keep them in the fridge, but you don’t need to. They’re perfectly able to hang out at room temperature on the counter and you can enjoy them as weird vegetal sculptures before you cook them.

Andy and the Crew at Mariquita Farm

© 2022 Essay by Andy Griffin

Photos by Andy Griffin and Starling Linden

Something to Crow About

Starr with a few crows in Palo Alto.

I’m booted up, caffeinated, mouse in hand, and ready to hammer out a petulant screed concerning the general carelessness in the fashion industry as concerns “seasonality.” But first, we need to address some scurrilous allegations and imputations that have been passed around about the genus Corvus.

Cattle form a “herd.” Bees “swarm.” “Geese flock.” Even Alligators only “congregate.” But when three or more crows gather together it’s a “Murder?” This terminology isn’t fair to crows. Yes, some crows can be naughty. And maybe crows poke their beaks into places they’ve not been invited, but Corvus family members are not straight-up killers like the hawks and eagles of the Falconidae. Maybe it’s because of their curiosity and willingness to go where they don’t belong that Crows, Magpies, and their cousins, the Ravens, ended up serving the mythic world as “spies for Odin,” and “messengers” for other Norse gods. Crows worked for Yahweh too; when Noah wanted to see if the world flood that God had let loose was receding, he let loose the raven to fly over the waters the way a modern day General might send forth a drone. Of course, Noah’s raven didn’t come back. Religious scholars may differ on why a free bird didn’t return to the fetid, crowded ship full of bawling, mooing, barking, howling, braying, hissing creatures, but suffice it to say that the Corvus family doesn’t need humankind to survive. After the glow of our man-made Apocalypse has faded, and the radioactive ashes have settled, the crows will still be here, along with the seagulls, cockroaches, coyotes, and raccoons. Corvids are smart birds.

I’ve seen the damage crows can cause but their crime was greed and not malice, the way a murder is. In the early 1980s, when I worked at Star Route Farm, in Bolinas, we planted out the lagoon field in pumpkins and gave the land a light sprinkling. We were confident that once the pumpkin seeds germinated their roots would soon penetrate the rich soil and reach the abundant groundwater. We speculated that we’d be able to essentially dry-farm the pumpkin patch to a successful harvest. The pumpkins germinated. As each seed sent down the radical, or first root, into the soil, the two fat, green cotyledons of the sprout pushed out of the soil into the sunlight, still wearing the now empty husk of the pumpkin seeds like little hats. A “murder” of crows passed by and saw the fresh sprouts. They wanted to fatten up on some tasty, rich pumpkin seeds so they tugged at the husk. The crows succeeded in pulling the tiny plants from the ground but each sprout was a disappointment because the oily seeds had burned up all their nutritious oil and rich flavor. The crows hopped from sprout to sprout, tugging at the seed husks until the entire crop was uprooted. The day after the crop germinated the field was bald of any pumpkin spots. Luckily, it was early enough in the season so that we could re-plant the crop. When we set out the second crop of pumpkins we used transplants instead of directly sowing the seeds, and we carefully pulled any seed husks that still clung to the cotyledons before we popped the little plants in the soil. And we put out scarecrows.

It’s not clear to me that scarecrows actually “scare” any crows, but putting them in the field like sentries does help a farmer feel like they’re doing everything they can to produce a good crop. Once the early, cold, hungry months of spring are past, there’s generally enough food around for crows to survive without worrying a garden to death. Crows are opportunistic; they’ll eat bugs, worms, insect eggs, seeds, and carrion. They’re like coyotes in that respect, always on the lookout for an opportunity. But crows are not malevolent by nature; they just fulfill a niche that awards them for being nosy, indelicate, and persistent. And, like the coyote, crows can be loud. To call a group of crows a “murder,” is to devalue the role they play in a healthy, balanced natural ecology. I suggest that we “re-brand” the crows that flock together as a “caw-cawphony” of Corvids.

It’s not clear to me that scarecrows actually “scare” any crows, but putting them in the field like sentries does help a farmer feel like they’re doing everything they can to produce a good crop. Once the early, cold, hungry months of spring are past, there’s generally enough food around for crows to survive without worrying a garden to death. Crows are opportunistic; they’ll eat bugs, worms, insect eggs, seeds, and carrion. They’re like coyotes in that respect, always on the lookout for an opportunity. But crows are not malevolent by nature; they just fulfill a niche that awards them for being nosy, indelicate, and persistent. And, like the coyote, crows can be loud. To call a group of crows a “murder,” is to devalue the role they play in a healthy, balanced natural ecology. I suggest that we “re-brand” the crows that flock together as a “caw-cawphony” of Corvids.

I also call upon the fashion industry to rethink their tired efforts at dressing our nation’s scare crows as a gesture of respect for nature. Why, if the point of putting a scarecrow into a field is to scare off the crows from the recently sprouted crops in the spring, or from the first ripe berries and fruits of the early summer, are scare crows only given attention in the fashion press in the fall? And why are the scare crows so typically draped in dreary rags? The crows that these scarecrows are supposed to be scaring always look their best in shiny, iridescent, black plumage. Maybe the designers that plot the fall fashion lines for scarecrows want the crows to actually die laughing at the hideous overalls and straw hats that the scarecrows must typically wear. Wouldn’t it be more fun and effective to dress the scarecrows in the neon outfits that bicyclists favor? Or how about those insane golf pants that old guys wear on the links- those are scary as hell….Wedding dresses could be repurposed for scarecrows too, once the lifetime union of two souls has been torn asunder by infidelity or dishonesty and the dress simply hangs in the closet as a reminder of disappointment. Crows aren’t use to seeing these kinds of garments on the scarecrows and maybe they would find the novelty of new outfits alarming. Each winter the fashion world could have their models walk the runways festooned in the newest, most lurid and alarming styles that will soon be seen in the nation’s gardens and farms.

I also call upon the fashion industry to rethink their tired efforts at dressing our nation’s scare crows as a gesture of respect for nature. Why, if the point of putting a scarecrow into a field is to scare off the crows from the recently sprouted crops in the spring, or from the first ripe berries and fruits of the early summer, are scare crows only given attention in the fashion press in the fall? And why are the scare crows so typically draped in dreary rags? The crows that these scarecrows are supposed to be scaring always look their best in shiny, iridescent, black plumage. Maybe the designers that plot the fall fashion lines for scarecrows want the crows to actually die laughing at the hideous overalls and straw hats that the scarecrows must typically wear. Wouldn’t it be more fun and effective to dress the scarecrows in the neon outfits that bicyclists favor? Or how about those insane golf pants that old guys wear on the links- those are scary as hell….Wedding dresses could be repurposed for scarecrows too, once the lifetime union of two souls has been torn asunder by infidelity or dishonesty and the dress simply hangs in the closet as a reminder of disappointment. Crows aren’t use to seeing these kinds of garments on the scarecrows and maybe they would find the novelty of new outfits alarming. Each winter the fashion world could have their models walk the runways festooned in the newest, most lurid and alarming styles that will soon be seen in the nation’s gardens and farms.

Andy and the Crew at Mariquita Farm

© 2022 Essay and Photos by Andy Griffin

And, something to crow about…check out this article in Edible Monterey Bay, “Cactus, Citrus and Cauldrons at Mariquita Farm” by Laura Ness.