A Field with a View

Mt. Shasta looms over Redding, CA

What’s the stupidest thing you’ve ever done?

I’ve been busy in that respect but, with Mt Shasta as my witness, I have to say I’m lucky to be alive today. It happened a long time ago, but there are some “teachable moments” in my farce, so let me tell you the story.

Mount Shasta looms over much of northern California like Fuji over central Honshu: majestic, sacred, and iconic. When I was 16 years old I took my first job away from home working on a ranch just north of Shasta, and I never got tired of taking in the view. Because we’re about to start our farm’s harvest share program in the Bay Area for the 2022 season, and because I know I’ll be frantically busy for the next eight months, I decided to take a brief road trip up to Portland last weekend to visit my daughter, Lena, who works as a baker there. The drive north took me straight up I-5 and past Mt. Shasta, which stirred up a lot of memories.

My father was a botanist, and I recall him saying that when he was a grad student in forestry at UC Berkeley in the early 1950s the air was still clear enough to get a view of BOTH Mt Shasta and Mt Lassen on the horizon from Vacaville. It might still be possible on a rare clear winter morning after a rainstorm, but as I drove up the valley the other day I was past Orland and I still couldn’t see the mountains. I did see a kid “pulling a tarp” in a field of alfalfa that was being flood irrigated though, and I had to laugh. Been there, done that…

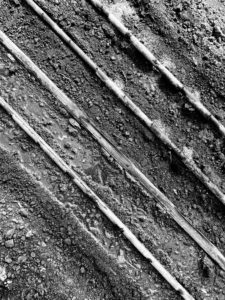

Drip irrigation tape wetting a sowing

On Mariquita Farm we have to be very conservative with water. We share the well with Hikari Farm, and the agreement we have with them is that Mariquita can water the crops every Monday, Wednesday, and Friday while they get to use the water every Tuesday, Thursday, and Saturday. And we only use drip irrigation, even to germinate the crops of greens.

But when I was working in the alfalfa fields in Northern California as a kid, we let the water flow across the landscape like there would always be plenty of rainy days. My father visited me on the Shasta ranch that summer and he shook his head in amazement when he saw me pulling tarps. “A crude, but effective method,” he said. “There are 5000 year-old hieroglyphics on stone walls in Egypt that show people irrigating this way.”

By “this way,” he was referring to the practice of flooding fields to irrigate them by using a series of ditches. It works like this: There’s a “Ditch Master” in charge of distributing the water of the district through a series of canals. When it’s your turn to receive your allotment of district water you need to be ready— it’s ALL the water you’re going to get, so you use it or you lose it, but you’re paying for it either way. Your ditches need to be clear of weeds or other obstructions, and you must make sure that no badgers or squirrels have burrowed holes in the banks which might leave tunnels that guide the water astray. And you need to have your stakes and tarps ready and in place.

When the ditch master turns the valve, the water rushes from the district canal down the empty ditch in a mindless hurry. It’s your job to discipline it. Every so often down the length of the ditch you need to have a sturdy log placed that spans the ditch and is firmly anchored in place. Beside this log you need to have a pile of sharpened sticks and also a heavy, canvas tarp. Before the water arrives at the first field you intend to irrigate you need to have already built your first dam. To do so you poke a series of sharpened sticks into the earth on the bottom of the ditch and then lay them up against the log that spans the ditch. Once constructed, the frame of your dam-to-be looks like ribs sticking down from a spine. Then you lay the tarp against the rib cage, from the top to the bottom, and the loose edge of the tarp is stabbed into the dirt with the point of the shovel. When the water arrives at the dam the tarp traps it, the dam restrains it, and so the water rises in the ditch until it overflows into the field.

As the water flows down the length of the field it is conducted and constrained through a series of “checks,” which are long, low parallel, raised mounds of earth—like speed bumps—which run the length of the field. While the irrigators are waiting for the water to adequately soak the ground they can usually use the time by building the next dams and tamping the canvases in place. That way, when it’s time to move the water they need do nothing more than “pull the tarp” from the upstream dam to release the water to flow further down the ditch. But you don’t “pull” the whole tarp at once—that would be hard to achieve due to the weight of the dammed water that pins the tarp to the wooden ribs—so you pull the top of the tarp down just a little so some water spills out, and then a little more, and a little more. Shenanigans can ensue, of course; your dam can break downstream if you release too much water too fast, or your tarp can get swept away in the flood as you release the water carelessly. Sometimes the ditch water has fish or snakes in it, or some other excitement. Back in the day in ancient Egypt an irrigator probably had to watch out for crocodiles. I had it lucky!

Once the ditch master opens the floodgates in a farm’s main ditch, the irrigators are busy until the water delivery contract has been fulfilled. On the day of “my greatest stupidity” we’d been irrigating around the clock for three weeks straight. We would do the short sets in the day and leave the longest sets for the night time so that we could get some semblance of sleep, but even at that I was getting up at 10pm, 12 am, 2 am, 4 am, and then we started the regular day at 6 am. So it’s fair to say I was very tired, and starting to get kind of dreamy in the afternoon. I had a field to irrigate that had over a hundred head of Brangus cattle in it. I set the tarp, let the water flow and looked south across the field at the dog and Mt Shasta.

The dog was always a help because she ran back and forth in front of the advancing water, so you could judge how far along the water had reached without actually walking the field yourself. And she busied herself snapping up the gophers that were driven to the surface by the flood. Sometimes she would even catch a fish. The water came out of the Little Shasta River and it had all kinds of creatures in it: turtles, crawdads, trout. And then Shasta. You can’t look at anything up there without having Shasta as a dramatic backdrop. I never got tired of looking at.

I’d been gazing at Shasta in a stupor for a while, and I heard a snuffling. I slowly looked about and saw that the cattle had gathered around me at some distance and were sniffing and ogling me, trying to figure me out.I stood there still as a post, and they slowly advanced as their curiosity overcame their fear. “I’ll bet this looks interesting from the air;” I thought to myself, “these cattle gathering around me in a ring. If I wait until they’re really close, then startle them, it would probably look like an exploding meat flower.”

And that’s exactly what I did: When the cattle got so close that I could smell their breath, I jumped up and yelled! They bolted in a panic. It probably did look like an exploding meat flower if observed from above. I certainly scared the shit out of them, and I had to walk through it as I went to pull my tarp and move on to the the next set. I’m lucky they didn’t trample me. And I feel bad about it now, because it wasn’t a nice thing to startle the cattle, and I do like cows.

By the time I got to Red Bluff I could see both Shasta and Lassen. It was a beautiful day. The weather has warmed up a lot, the soil is warm, and it’s time to plant tomatoes next week.

© 2022 Essay by Andy Griffin.

Photos by Andy Griffin